TOM: A train and a couple of buses from Edinburgh over to Cample Line in rural south west Scotland. We’re here to see The Unbearable Halfness of Being, a solo show by Palestinian artist Jumana Emil Abboud, who lives and works in Jerusalem and London. A quick confession: Cample Line is probably my favourite gallery in Scotland. I’ve written about them a few times, including a catalogue text for them a couple of years back, so I am biassed. But mostly it’s because their programming is always so thoughtful, while the place itself – the old cottage buildings, the surrounding agricultural landscape – creates a very specific context for the work. There’s also something about making a commitment: when you go to Cample Line from Edinburgh it’s a full-day thing.

CRYSTAL: Both of us really wanted to see this exhibition, in part because of everything that’s happening in Gaza right now, and elsewhere across occupied Palestine.

TOM: Yes, and in their own understated way, Cample Line have been consistently vocal in solidarity with Palestinian people, perhaps in part because of Jumana’s exhibition.

CRYSTAL: There’s recently been a big exhibition of Palestinian embroidery at Kettle’s Yard, which just transferred to the Whitworth, and the silence from both institutions has been unsurprising but disappointing. The fact that Cample Line has publicly voiced support for Palestinian solidarity alongside showing Jumana’s work feels so, so important right now, especially considering how many Palestianians have been demanding exactly this support.

But to refocus on the exhibition, one of the things I especially loved was the artist interview film.

TOM: Yeah, Emma Dove makes Cample Line’s exhibition films – they’re always brilliant.

CRYSTAL: In the interview, Jumana speaks about how her priority is to connect with the landscape through its magic rather than through its politics. And by this it’s very clear that she isn’t demeaning or belittling a political reading of the landscape. There’s an acknowledgment of the work done by others in that area and a statement of desire to resist, as Jumana says, viewing the landscape through the lens of the coloniser.

TOM: Exactly. The phrase she uses is “I don’t want to be absorbed into the political reading of the landscape.” So I guess it’s not to pretend that landscape isn’t political (which I see in so many otherwise ecologically-minded artists and writers) but a question of how to retain/assert agency given the inescapable political context of occupation. Like, the hilltop military outposts and the illegal settlements are there in the films and they are mentioned but they are nowhere near the heart of the narrative. Both/and, as you always say.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, I love a both/and. It speaks to the multiplicities we carry within us as well as the complexities of the subjects and contexts artists make work about.

So, we went round the exhibition in slightly different ways. You stayed downstairs to watch the three films made by Jumana and Issa Freij and I went upstairs to look at the paintings, drawings and material objects. Maybe we can start with the latter and come back to the films.

TOM: Sure.

CRYSTAL: I think we both gravitated towards the wax objects and the embroidery pieces.

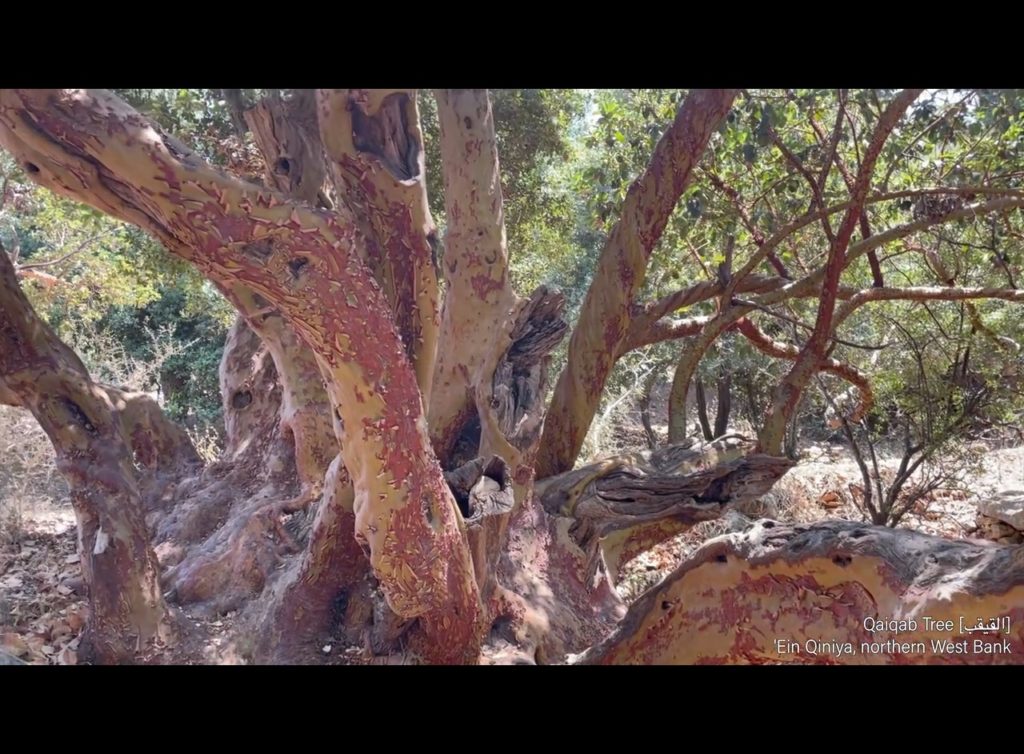

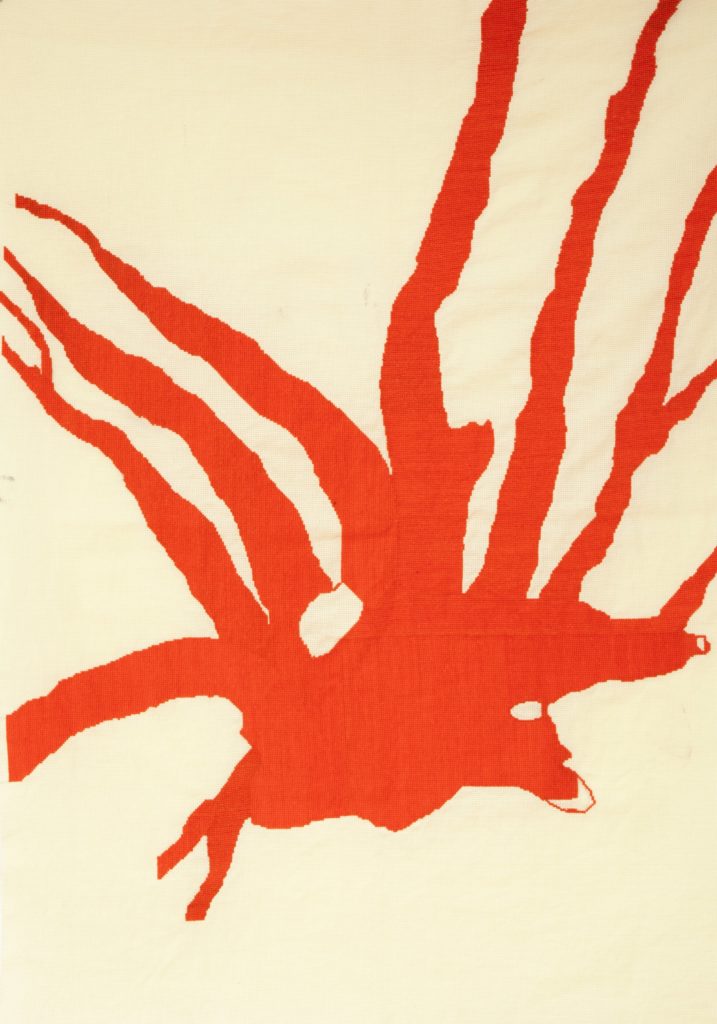

TOM: Loved them. One thing that struck me – in part because I just wrote a critical review of an artist who does the opposite – is the nature of Jumana’s collaborations. She names the people she works with, in the films, in the lists of works. You get a sense of a genuine collaborative process, people working together as part of a collective, not one person using the labour of another and calling it collaboration. I especially loved one of the embroidery pieces, An enchanted tree (Large qaiqab, Greek strawberry maple). It’s a flame-red silhouette of an ancient and symbolically important tree, made in collaboration with Suha ‘Atta ‘Alqam, a craftswoman in the West Bank village of ‘Ein Qiniya, where Jumana had been on residency with multi-arts and ecology organisation Sakiya.

CRYSTAL: I was mesmerised by that embroidery piece. I’ve never seen a qaiqab tree before and there was a brief clip of one in the interview film. Even just from a brief glimpse on a screen, you can understand immediately that it’s a sacred tree. I think that quality comes across in the embroidery piece, too. I loved all of the embroidery pieces actually, like Crochet horse as guardian made by Jumana’s mother and Waves and hands. Like you mentioned, I also get the sense that the collaborations are very meaningful. I chatted with Tina [Fiske, Cample Line director] afterwards about how some of the community members involved in the water walks took ownership of the project, which I think is brilliant. And necessary. Community-based participatory projects don’t work unless those involved feel that they have some agency over the direction of the work. It also speaks to me as a counter to market-driven obsessions with individual authorship and ownership.

TOM: You can see that really clearly in one of the films, The Water Keepers. As the group climb the hill, reading fragments of poetry in unison as they go, there is one fellow with a walking stick and pleated dark green trousers who somehow exudes a sense of ownership over proceedings.

CRYSTAL: Ha, yeah, that’s exactly who Tina and I were talking about!

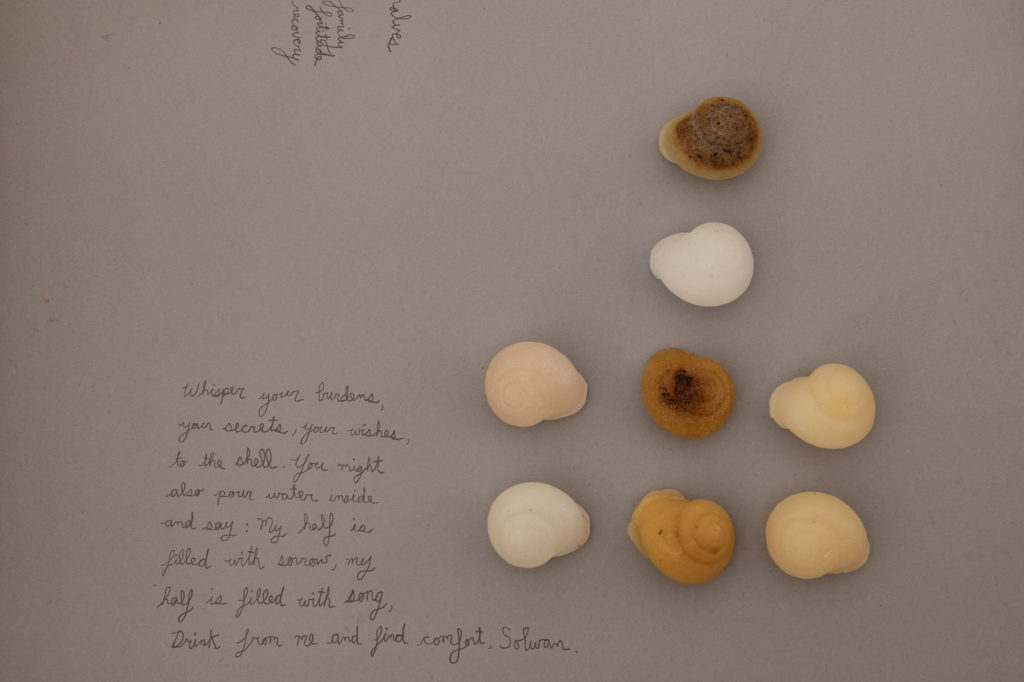

Relatedly, I think the wax objects are a wonderful extension of those ideas around community and the landscape and creating new myths from found objects. I loved the remark Jumana makes in the interview about how, when she first started thinking and theorising around halfness there was a lot coming to mind about how unbearable it was to be denied access to your story or your land, these aspects that make up our other halves. But, eventually, when she started to think about the idea of halfness through the divine walks to find water through metaphor, it became something exquisite and empowering rather than unbearable.

TOM: I think there’s something there about how words, ideas, landscapes and stories are all things that change through (collective) use. And in that sense they are active spaces, or spaces that can be activated. And that people being together in communities can help to steer that change themselves, with or against the wider flow of politics. There is one beautiful line in one of the films, Hide Your Water from the Sun I think: “…and no amount of trespassing will invade my gentle heart.” It’s an assertive statement, and one that speaks to both tenderness and resilience at the same time.

And I think maybe that links to the aesthetics of the exhibition, especially the way the votive wax objects are presented. These are objects found on the walks shown in the films, cast in wax, and then imbued by the temporary community of walkers with new meanings and mythologies. They’re displayed on a grey background in a vitrine and, in contrast to how the work was displayed at documenta last year, there’s no glass. It’s obviously very considered, but feels almost casual, like the objects have just been placed there for a moment, and they could be picked up again, used and put back. The notation is also in pencil, handwritten by the artist – it suggests a kind of knowledge that is provisional, not fixed into categories or hierarchies. A talisman is a functional object and the display is open and vulnerable, not overly precious.

CRYSTAL: The aesthetics of the paintings also felt very considered. There was such a thoughtfulness and intentionality around materiality, with resonances speaking of direct connections to the landscape. Things like the use of pomegranate ink and wax crayons made of earth taken from areas around different water sources. A lot of the colours reminded me of the Arizona desert where I grew up, the turquoises and blues and ochres, which hit me with a big pang of nostalgia. I have strong smell memories associated with that colour palette which also translates into memories of landscapes from home. That being said, if I’m honest, the figurative visual language of the paintings doesn’t really resonate with me.

TOM: One painting I did really like is Our other half (diptych), at the end of the room. Maybe something about the larger scale helped, or that it was more fully worked, with exactly the range of land-drawn materials you just mentioned. There was something about the way the figures seemed to emerge out of, or maybe blur back into, the washes of subtle colour, that seemed very intriguing.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, I loved all of the colour washes and the beautiful paper and the tones and mood of everything. But I struggled to connect emotionally with the figures. One thing that really did connect for me was the relationship between the gallery location and the work. You look up from an embroidery piece or painting meditating on enchantment and water to a view of a Scottish landscape, the river just there, sheep grazing over the hill. Being able to see out of the windows to the landscapes beyond was so perfect for this exhibition. Without having to materially add anything to the work, the setting brings an additional set of associations and resonances which I really appreciated.

TOM: I mean, that is the magic of Cample Line. It does that for every exhibition, each time a little bit different, and you can’t help but make your own connections.

Jumana Emil Abboud, The Unbearable Halfness of Being is at Cample Line until 17 December 2023.

Three films by Jumana Emil Abboud and Issa Freij are available to watch on the Cample Line website.

Image credits from top:

1. Jumana Emil Abboud, The Unbearable Halfness of Being, Cample Line installation view. Photo: Mike Bolam

2. Cample Line exhibition film, 2023 (film still)

3. Jumana Emil Abboud, An enchanted tree (Large qaiqab, Greek strawberry maple), 2021. Photo: Mike Bolam

4. Jumana Emil Abboud, The Water Keepers, 2021 (film still)

5. Jumana Emil Abboud, Pasts and Futures in Palm of Hand: the Water-divined Votive, 2022. Photo: Mike Bolam

6. Jumana Emil Abboud, Our other half (diptych), 2022. Photo: Mike Bolam