Advertising works. I kept seeing this book everywhere—on social media, in the news, on the shelves at my local bookstore. I like art. I’m an advocate for feminism, to use bell hooks’s preferred phrase. Surely, I’d get on well with this book. I bought it and started reading.

Unfortunately, the problems start on pretty much the first page. A short introduction sets out the book’s aims and models and both are questionable. There’s a nod to Linda Nochlin’s famous 1971 essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, but then we come to what seems to be the real inspiration for this book: E.H. Gombrich’s 1950 The Story of Art. ‘It’s a wonderful book but for one flaw’, author Katy Hessel writes. The flaw being that Gombrich didn’t give a damn about women artists: in the first edition, there were no women and even in editions as late as the sixteenth, that figure only ever tipped to one. Yet rather than reject Gombrich’s ‘flawed approach’, Hessel seems to want to recreate it, only this time ‘break down the canon’ and include the women. Wait. What? The canon. As in that outdated and sexist idea of a list of the most important works of art or literature or whatever, usually made up of 100% dead white dudes. I mean, I love (some, but not all) dead white dudes. But that’s not the kind of feminism I’m interested in. The fact that Hessel’s project takes for its centre of gravity a concept so deeply rooted in white supremacy and patriarchy speaks to a lack of critical engagement with feminist histories and historiography. For art historian Maura Reilly, ‘revising the canon to address the neglect of women and/or minority artists is fundamentally an impossible project because such revision does not grapple with the terms that created that neglect in the first place’.

I so wanted The Story of Art Without Men to be great, but it’s waging war against me on multiple fronts. Firstly, and perhaps most frustratingly, the ‘corrective’ approach to art history on display here, with its hyped-up narratives of ‘rediscovery’, is underpinned by a regressive girl-boss feminism that basically just wants women to have more shows at Gagosian and sell for more money at Sotheby’s. This is a feminism that superficially gestures in the direction of diversity and inclusivity without understanding the ways in which intersectional frameworks demand fundamentally different ways of doing things. It isn’t a feminism that seems interested in imagining a radically more equitable artworld/s for all participants. Elsewhere, I’ve written about the problems of the ‘hidden heroes’ trope or ‘forgotten’ women. These women artists were never hidden. They were members of families and artistic communities, they had relationships with patrons, collectors, curators and others. Visual culture theorist Ariella Azoulay has also pointed out that a major problem of alternative histories is that they propose ‘some things as “hidden histories” in need of discovery, [which are not] hidden things or histories but rather open secrets known far beyond the archive and the grammar invented as guardian of its orderly uses’.

Secondly, despite the long parade of names of women artists from the seventeenth century to today, the book’s politics suck. Without any real sense of self-awareness, The Story of Art Without Men enacts a huge erasure of other women. Namely, women (and men) art historians, academics, artists journalists, curators and other art workers. Not a single one of the words written in this 450-page book would have been possible without the vital contribution of the people who have dedicated themselves to the study of the artists mentioned throughout. As far as I can tell, Hessel’s book is not one of original research and scholarship, but a combination of facts cribbed from other academic and popular texts and blog-post casual reflections on her favourite artworks. Despite a brief, generic acknowledgement in the introduction, the work of these (mostly) women has been completely sidelined. Yes, there are limited notes and bibliography at the back of the book, but this is token in comparison to the general erasure and complete absence of those who have done the intellectual work which underpins this book. I also feel that there’s a complete lack of understanding that constantly promoting the argument that women have been systematically excluded from art history, without any nuance or specificity, in turn acts to erase the last fifty years of feminist art history.

For example, at the end of the two-and-a-half-page section on eighteenth-century Venetian pastellist, Rosalba Carriera, who painted Louis XV and received honorary membership to the Académie Royale, Hessel writes that by the time the French Revolution turned up, Rococo fell from fashion and ‘for centuries, Carriera was forgotten’. The implication being, naturally, that it is thanks to this book that Carriera is being rescued from obscurity. In the notes section, there’s a link to an article on Christie’s website (from which Hessel seems to have paraphrased), a two-page citation to another recent ’women artists’ compilation book, and only one citation to a book actually about Carriera: Angela Oberer’s 2020 The Life and Work of Rosabla Carriera: The Queen of Pastel. Where is Bernardina Sani’s 2007 catalogue raisonné (published in Italian)? Or the extensive entry on Carriera by Neil Jeffares—who has dedicated his entire career to pastellists—in his Dictionary of pastellists before 1800? Or Julia Dabb’s anthology, Life Stories of Women Artists 1550-1800 (2009)? Why not mention the early-twentieth-century monograph by Emilie von Hoerschelmann (written in German)? What about the exhibitions of her work in Karlsruhe in 1975 and in Venice in 1994, 1997 and 2007? Or is an artist only forgotten if they aren’t being written about in English and exhibited in London and New York?

Similarly, a chapter on quiltmaking opens with the line, ‘Art historians have overlooked quilting as a key medium for far too long’. Whenever I see a sentence like that, my first thought is that whoever wrote it probably hasn’t taken the time to actually look and see who has been doing the work. If Hessel had taken as much care to respect the work of women intellectuals as she claims to respect women artists, then she might have paid tribute to work done by pioneering Black scholars like Cuesta Benberry who dedicated her professional life to African-American presences in American quilting, or Gladys-Marie Fry, whose 1989 book Stitched from the Soul: Slave Quilts from the Ante-Bellum South was one of the first books to look at the role of quilting among enslaved communities in the U.S. Fry’s work demonstrated that it wasn’t only African American women who made quilts, but African American men, too, enslaved men among them. The complexities of these and other histories speak loudly as to why the overly-simplistic ‘inclusion/exclusion paradigm’ (a turn of phrase borrowed from Dr. Kimberly Schreiber) followed by Hessel is completely regressive. Or, as Virginia Wolf put it, ‘in relation to women writers, you have to leave room to deal with other things besides their work, so much has that work been influenced by conditions that have nothing whatever to do with art’. When you try to cram 500 years of art history into a single book, with each artist getting no more than a few paragraphs, there’s simply no way you can address any of Woolf’s ‘other things’ (by which, just to be absolutely clear, I mean, things like class and race, family connections and networks, or caring responsibilities).

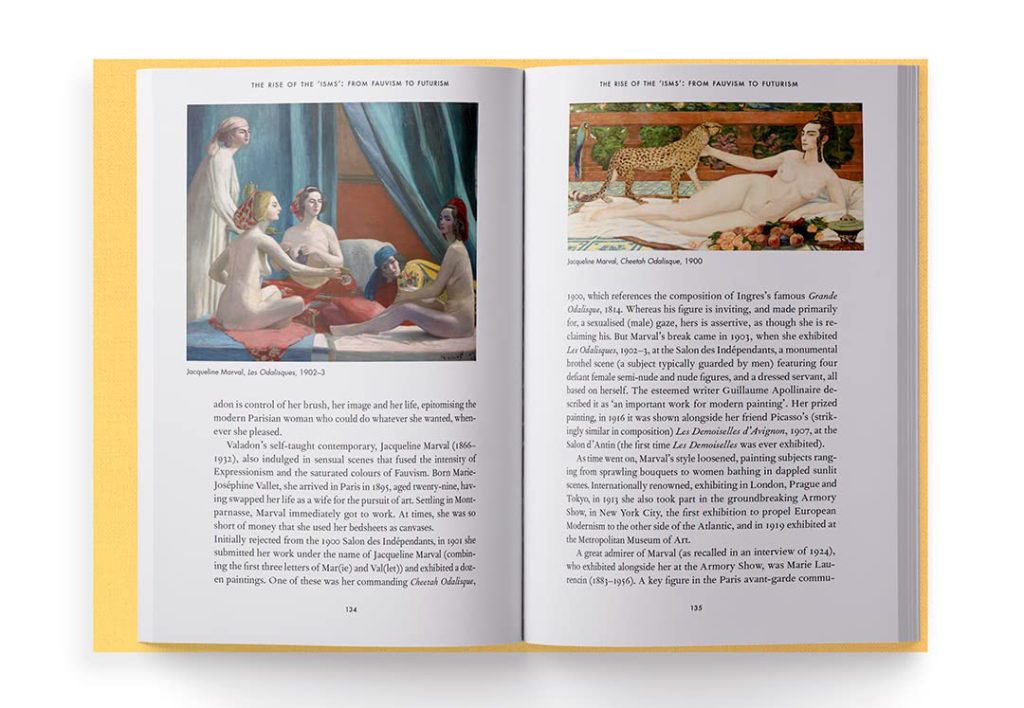

Hessel’s blinkered feminism causes other problems, too. Just as the book seems mired in its obsession with rediscovery, the canon and downplaying the contexts and communities in which women worked, so too is there an inability to address difference with a critical eye. Women, here, are flattened into a single entity: artists. Because of this, many of them are celebrated as ‘rebels’ or ‘game-changers’ and written about in the language of pseudo-feminist hero-worship. Repeating the most sensational aspects of their lives—which ironically, almost always feature male, sometimes female, lovers—the book repeats the same soundbites so beloved by publicity departments in big museums and galleries to promote their blockbuster exhibitions of ‘newly-discovered’ women artists. To get big audiences through the doors, and help pay for the expensive solo exhibition, museums hawk their exhibitions of women artists as being about ‘rediscovered rebels’ rather than as artists. This is how we come to hear more about Artemisia Gentileschi as a rape victim, Frida Khalo’s tempestuous marriage to Diego Rivera, and Camille Claudel as a woman spurned by Rodin. When we hear or read more about these women in terms of things men did to them than we do of their work as artists or the richness of their lives as women, both aspects are trivialised. And in a book like this, where women artists are flattened into a single entity, there are some alarming instances where uncritically celebrating artists for their sole virtue of being women is more important than taking an informed, critical approach to their output.

A good example is the short section on photographer Diane Arbus. Much revered in the commercial art world, Arbus’s work remains controversial and contested. Yet Hessel either ignores or is ignorant of the fact that there are still many who take issue with Arbus’s portraits of those who she calls ‘on the “fringes” of society—drag queens, circus performers, strippers, sex workers’. While you could argue, as plenty have, that Arbus championed normalising representation of marginalised groups, it’s difficult to make the same argument for the images she took of the men and women living in New Jersey residences for developmentally and intellectually disabled people between 1969 and 1971. Following the 2003 release of many of Arbus’s letters and journals, certain voices (Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker, among others) insisted that Arbus wasn’t voyeuristic but empathetic, but such arguments ring hollow to me. Hessel notes that Arbus’s images were controversial in their day—as if the controversy has come to an end—but insists, in her ever-positive voice, that they ‘document an unfiltered depiction of a world so often dismissed from art history and sidelined by society’.

While the intention of this book is laudable enough, as I tell my students regularly, intention is only one side of any story. The Story of Art Without Men presents itself as a radical feminist history of art, but it is far from it. Beyond providing a helpful catalogue of names of women’s artists, its politics are a problem. It is superficial, lacking in criticality and depth. It perpetuates the erasure of some women’s work while purporting to celebrate that of others. If you’re looking for feminist art histories about women artists, look to Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock, to Kellie Jones and Lisa Gail Collins, to Norma Broude and Mary Garrard. Look anywhere else, but not here.