The Penitent Review is often a place where we complain about aspects of the art world in ways that the usual magazines are less inclined to publish. But we also like art (sometimes)! So we thought we’d run through a list of some of our favourite shows of 2025. Tom’s highlights were mostly in the UK, in part due to a comparatively low-travel year, while jet-set Crystal visited exhibitions all over the shop. For both of us, most of what we connected with this year was intimate and small scale: solo presentations and films rather than big group shows or biennales.

Fenix, Rotterdam

I was pleasantly surprised by the depth and complexity of the work on display in this new museum of migration, particularly the decision to position contemporary art next to historical records and artefacts. We’re here because you were there connections abound: a framed money exchange note given as compensation to a Dutch plantation owner in Suriname following the 1863 abolition of slavery hangs across the room from Adrian Paci’s striking short film Centro di Permanenza Temporanea (2007), in which men crowd onto an aeroplane boarding staircase leading nowhere and wait. I was particularly taken with Beya Gille Gacha’s Hands (2021-2023), capturing the lively language of gestures and adorned with thousands of exquisite turquoise beads from her mother’s native Cameroon, and Mario Sergio Alvarez’s De Tuin (2023), details of “exotic” plant species depicted in a Dutch book painted lush and loose on salvaged wooden cabinet doors from his first job in the Netherlands tearing apart old kitchens. While much work was, unsurprisingly, emotionally heavy, Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Migrants Who Don’t Give a Fuck (2019)–prints of flamingos overlaid with the work’s title – brought humorous defiance to the oft-used trope of birds symbolising freedom of movement.

(Crystal)

Hessam Samavatian, Earendel – Ab-Anbar, London

Ab-Anbar is one of London’s best galleries, unafraid to be intellectual and political as well as poetic. Hessam Samavatian’s solo exhibition was a beautiful showcase of cameraless photography that included works on paper, wall-mounted plaster images and tiny, delicate porcelain sculptures. I particularly liked a cluster of ceramic pieces, each one like a rough-hewn roof tile, with a thumb pushed through to tear a little raised hatch. Coated in photosensitive emulsion and lit from one angle, the ceramic darkens except for where the hatch casts a shadow, which remains pale. The accompanying text describes them as “sculptures that hold their own shadows”. I also loved a series of tiny wall-mounted works, Glass Pieces (2025) consisting of shards of glass from a photographic plate, behind which were mounted prints made using an analogue process involving those very same glass shards. I didn’t love everything in this show (some of the poetic imagery felt a little tired) but, at its best, this was an exquisite exploration of light and time, resilience and fragility, and the trace as a site of lingering and loss.

(Tom)

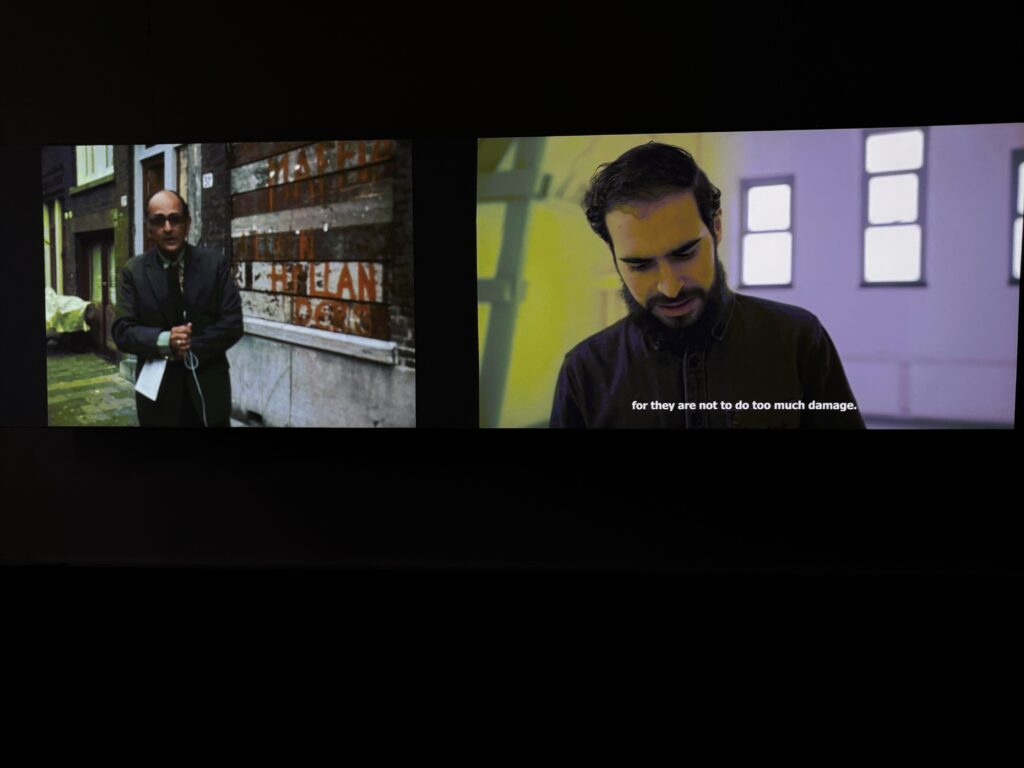

Cihad Caner, (Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghosti – Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam

Caner’s multi-media exhibition draws on a largely-forgotten history of racist rioting in Rotterdam in 1972. After a Turkish landlord evicted a Dutch woman, Dutch anti-immigration protestors destroyed homes across the majority-immigrant neighbourhood, Afrikaanderwijk. Caner’s two-channel video installation holds the show. Archival news footage of the riots is set alongside a contemporary re-enactment: not quite a literal recreation, but loose, informal readings of transcripts of the archival footage. The emotional distance of Caner’s re-enactments becomes a magnifying glass for the archival footage, underscoring the violence of the 1972 riots and the language used to report on them. A layered and thought-provoking show on the processes by which collective memories of violence are lived, fixed and forgotten.

(Crystal)

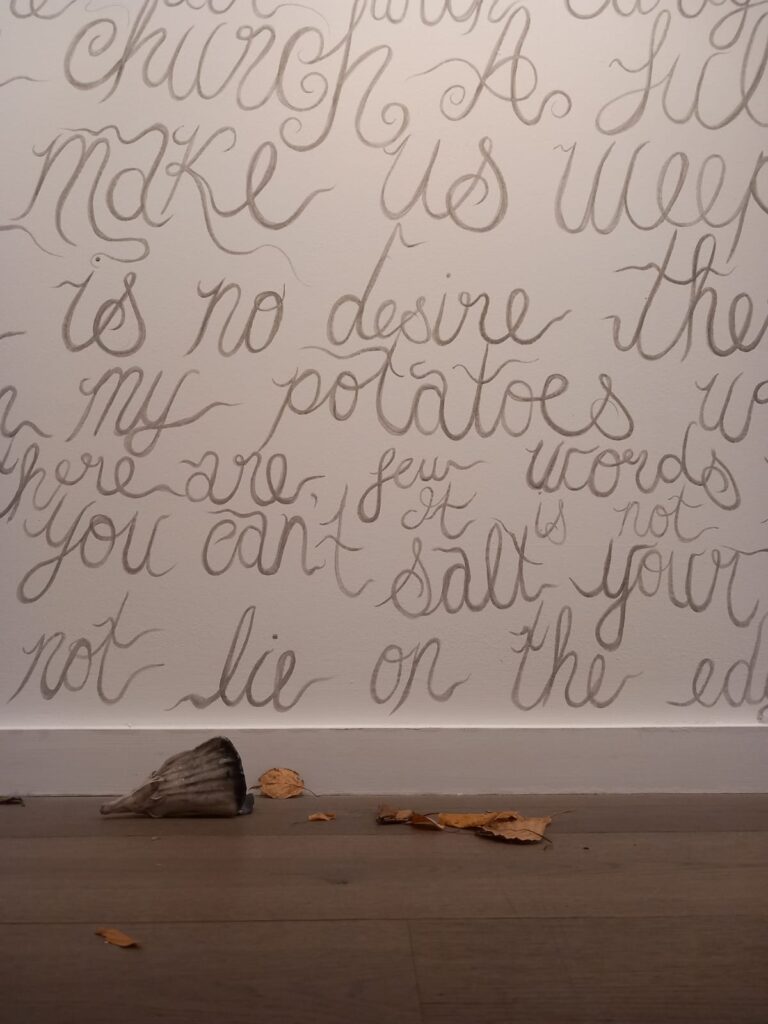

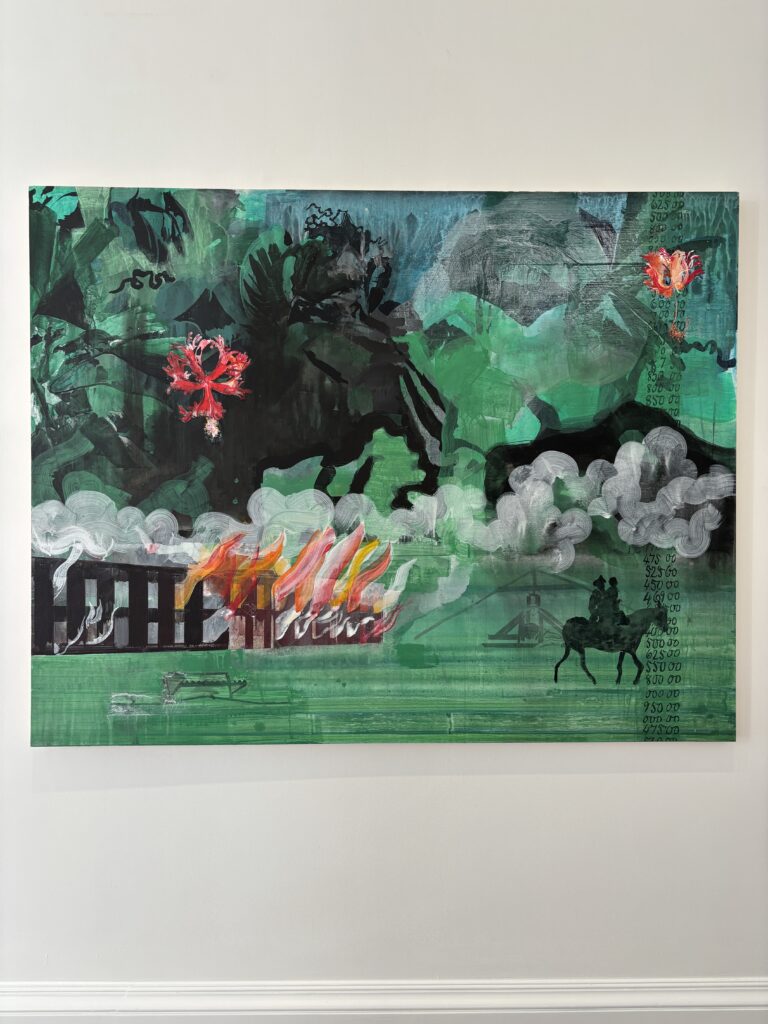

Ayla Dmyterko, Ring Around the Sun & We Rage On – Alma Pearl, London

Ayla Dmyterko is an artist whose work I’ve been following for the past few years so I was excited to see her solo show at another of my favourite London galleries, Alma Pearl. Ayla is nothing if not ambitious in the range of media she engages with: painting, performance, writing, film, installation, sculpture… The new show also includes ceramic sculptural pieces and large-scale wall works of long looping lines of text. All of this is imbued with precise historical research, an expansive sensitivity to mythology and, I would say, a necessary righteous anger. This show draws together a wealth of running themes, histories, and folklore, navigating diasporic traditions as they bloom or ossify in relation to patterns of colonial oppression, trauma and resistance. Ayla is a rigorous thinker and also kind of a magician, making work at once immersive and explosive. Daisy Lafarge’s essay that accompanies the show is absolutely incredible, because of course it is.

(Tom)

Outi Pieski, Eatnamastit – Malmö Konstmuseum

I was lucky to catch this comprehensive survey of Sámi artist Outi Pieski’s practice as it coincided with my own exhibition in Malmö this summer. Not all of the works resonated, but I was captivated by Pieski’s long-term collaborative project (2018-2023) with Finnish researcher, Eeva-Kristiina Nylander, on the distinctive ládjogahpir hats worn by Sami women until the early twentieth century. I never knew that the hats were condemned as satanic by Christian missionaries, contributing to their erasure among Sámi women. As Pieski highlights via a photographic taxonomy of hats trapped in museum collections, most ládjogahpir hats today are found in ethnographic museum displays. Pieski’s decolonial project centres on reviving the hats – relearning with other Sámi women how to make and wear them – through new creations, presented alongside a moving film in which an old and new ládjogahpir meet in a symbolic rematriation.

(Crystal)

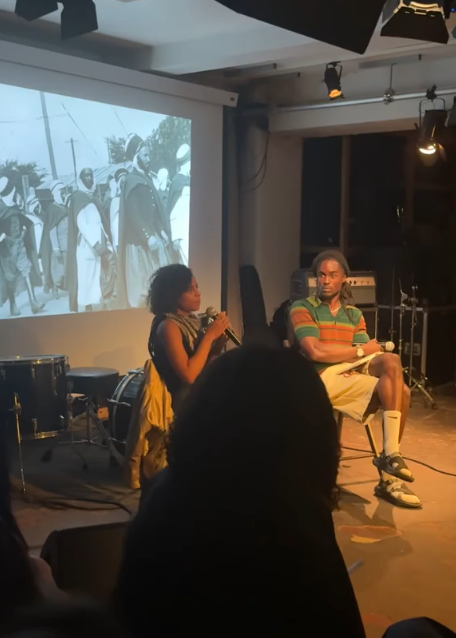

Regular Working Group – Cafe Oto, London

Formed, in their words, “as a response to the glaring failures of art in the face of the genocide in Palestine”, the Regular Working Group is “a musical programme that turns artistic failures on their heads”. Curated by Palestinian artist and sound researcher, Bint Mbareh, this particular night at Cafe Oto was a brilliant, surprising combination of sensitivity, insight, solidarity and rage. Experimental music collective 1000 Pounds to Survive Us set a familiar Cafe Oto vibe with ambient experimental music combining looped sounds and song. Chairs pushed out the way, hardcore punk band Ikhras lit the place up with a furious torrent of anti-zionist bangers. Their cathartic screaming cleared a path for another brilliantly crafted vibe shift: a beautiful, thoughtful discussion between designer and researcher Akil Scafe-Smith and cultural historian Alia Mossallam, which centred on music as a form of popular resistance to occupation. The whole night was an absolute education. As Ikhras’ lead singer said between songs: “only two words mean anything over the past two years: fuck Israel”.

(Tom)

Noor Abed and Haig Aivazian, Nothing will remain other than the thorn lodged in the throat of this world – The Common Guild, Glasgow

Sometimes noise can express rage and frustration with more affective force than language, and Noor and Haig’s collaborative performance was one of the most powerful things we saw together this year. Sound bleeds across borders, for example between inside and outside the body: the particular frequency of occupation drones vibrates with the force of screams. Repeated exchanges of formulaic pleasantries (Are you ok? Is your mother ok?) spoke to the limitations of language during genocide, but the necessity of speaking – and listening – nonetheless. The triangular staging of this Glasgow iteration meant that every action took place against a background of seated audience members – mostly prominent folks in the Scotland art world whose inertia on Palestine over the past two years has been a source of widespread anger. Thinking back, I’m reminded of Batool Abu Akleen’s collection, 48kg. One particularly graphic poem dramatises the double pain of being subjected to violence and not being able to speak of it. The poem tells of a severed hand longing to return to her person: “She wants to yell out, to scream, to call for him, / but she cannot find a mouth to call him with.”

(Tom & Crystal)

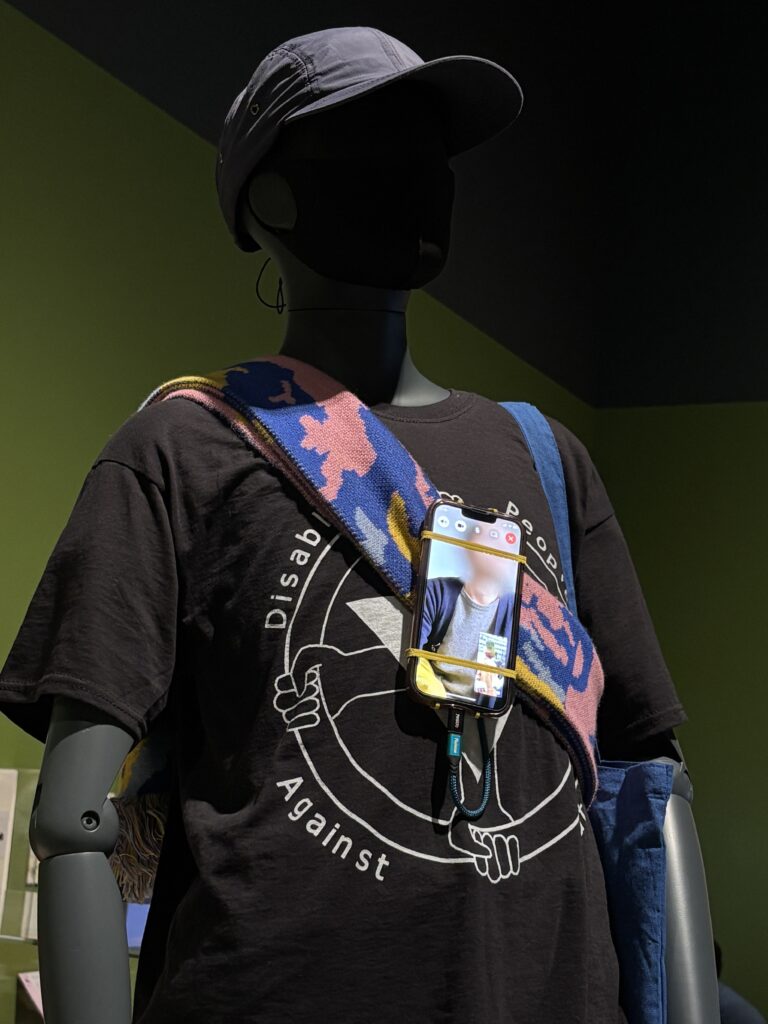

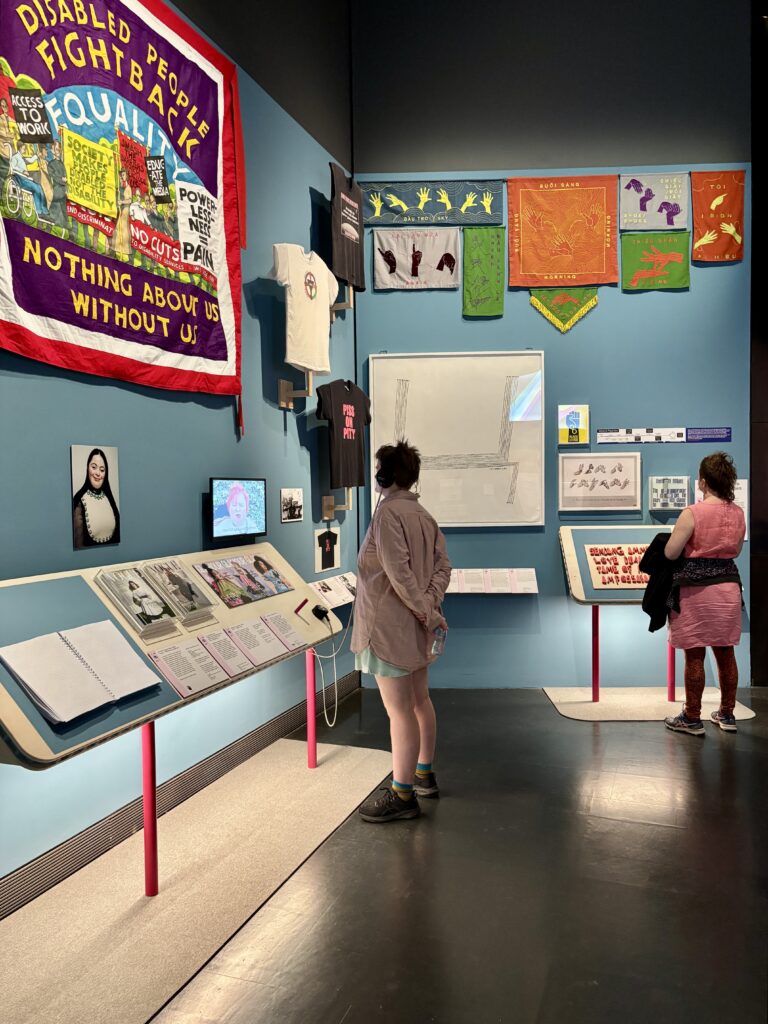

Design and Disability – V&A, London

More design than art, but I loved this radical, intelligent, political and pluralistic exhibition curated by wonderpal, Natalie Kane, with Reuben Liebeskind and Cat Macdonald at the V&A. Framed around the argument that Disabled people are not problems in need of design solutions, but creative and resourceful agents of more equitable design practices, the show also steered well clear of reductive essentialism. I loved Emily Sara’s 504 typeface in honour of the 1977 U.S protests demanding greater accessibility for Disabled people; the proxy protest tool kit, which allows anyone unable to attend a protest in person to participate via a harness-wearing proxy for live-streaming, created by Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrave and Kaiya Waerea; and the Gaza Sunbirds display of a bike and jersey from the noted Palestinian paracycling team based in the Gaza Strip.

(Crystal)

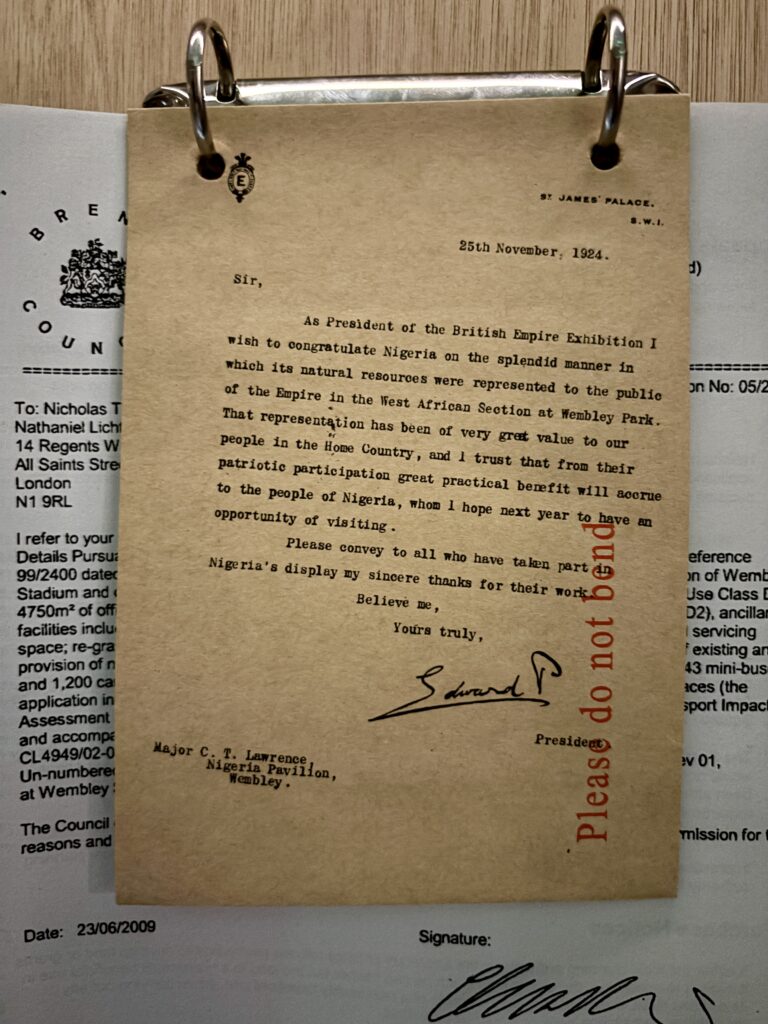

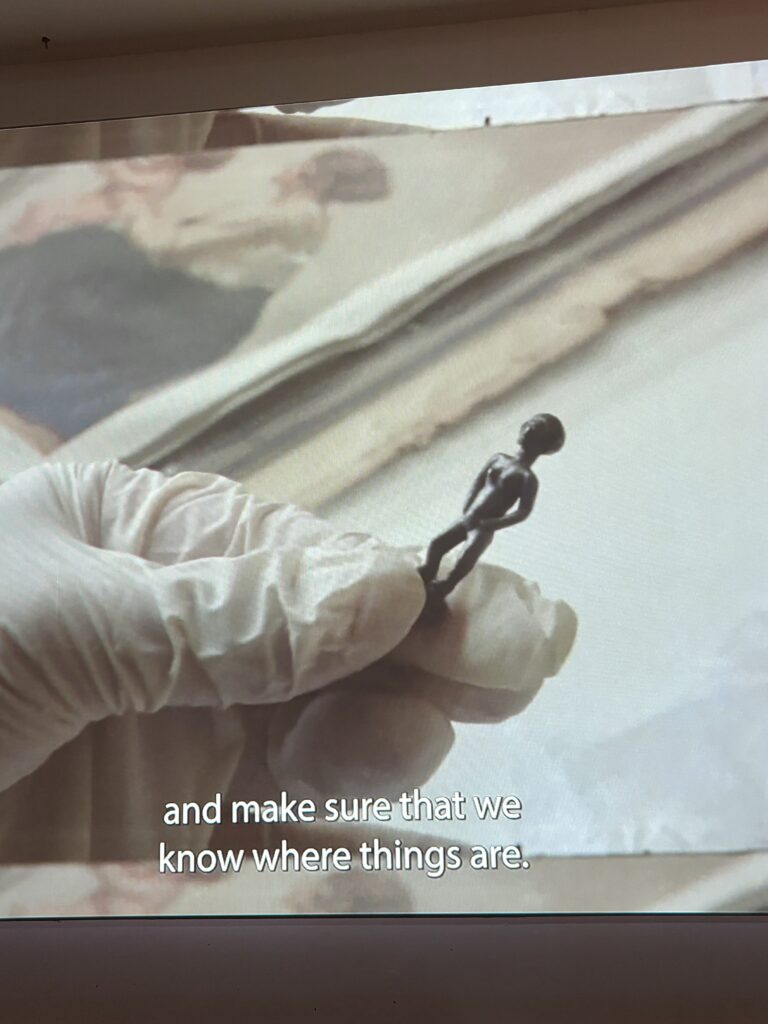

Arwa Aburawa and Turab Shah, The Park (Dancing on the Rubble of Empire) – Metroland Cultures, London

This film was originally co-commissioned by Brent Museum and Film London and stems from material discovered in Brent Archives relating to the 1924-25 British Empire Exhibition and the history of Wembley. Grounded in conversations with Wembley residents, the film unfolds in parallel to a loose narrative exploration of the Empire Exhibition, particularly the destruction of the temporary buildings and the later transfer of some of the rubble to create Northala Fields public park in London. In addition to archival materials exhibited in the gallery, the film itself navigates between digital video, 16mm film, archival footage and direct animation. While park users and local residents are, like the two of us, mostly unaware that Northala Fields was built from the remains of the Empire Stadium, the present significance of this history is an open question. For some, it seems heartbreaking; others joke that, after such a celebration of imperial violence, providing new public infrastructure is the least the authorities can do.

(Tom & Crystal)

Hilton Als, Jean Rhys in the Modern World – Michael Werner, London

For an exhibition purporting to be about Jean Rhys, writer Hilton Als was clearly the sun around which the assembled works – by artists ranging from Hurvin Anderson to Gwen John – orbited. Als’s third such love letter to a literary inspiration, after Joan Didion and James Baldwin, this wasn’t exactly a favourite exhibition, but it was one of the more original curatorial conceits I encountered this year. Not 100% sure I buy the tacit argument that Commander of the British Empire, Rhys, was a perpetual outsider, but Als’s unashamed appropriation of artistic works to reassign new meaning in the context of a creative construction of a biography of a third subject is certainly an intriguing method of exhibition making.

(Crystal)

Andy Goldsworthy, Fifty Years – National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

This is precisely the kind of comprehensive retrospective that national art institutions are for. I loved Andy Goldsworthy’s work after my brother gave me one of his photobooks as a child. But times change and love can fade or turn sour. Like many people, I liked a lot about this show: Goldsworthy’s embodied relationships to place, his precise, confident and surprising responses to the gallery spaces, his boldness, his subtlety, his self-deprecating sense of absurdity, his detailed attention to materials. I especially enjoyed the surprisingly abrasive, almost violent, installations of barbed wire and oak branches. But, like all good retrospectives, this exhibition not only showed the artist’s great strengths but his limitations too. In my 1990 book, he thanks the Duke of Buccleuch for gifting him “a small piece of woodland” in which to work. 35 years on, Goldsworthy is still doffing his cap to Buccleuch, one of the most powerful landowners in a country with some of the most unequal ownership in the entire world. Goldsworthy is occasionally held up as an exemplar of a caring, slow-attuned relationship to the natural world, but in barely engaging meaningfully with land ownership or ongoing processes of dispossession, he misses many salient questions. As a result, his work is rarely able to foreground collaboration, collectivity or emancipation. If Goldsworthy could combine political awareness with his undoubted strengths, then he really would be one of the greats.

(Tom)

Daniel Ward, Lonesome Ghosts – Peer Gallery, London

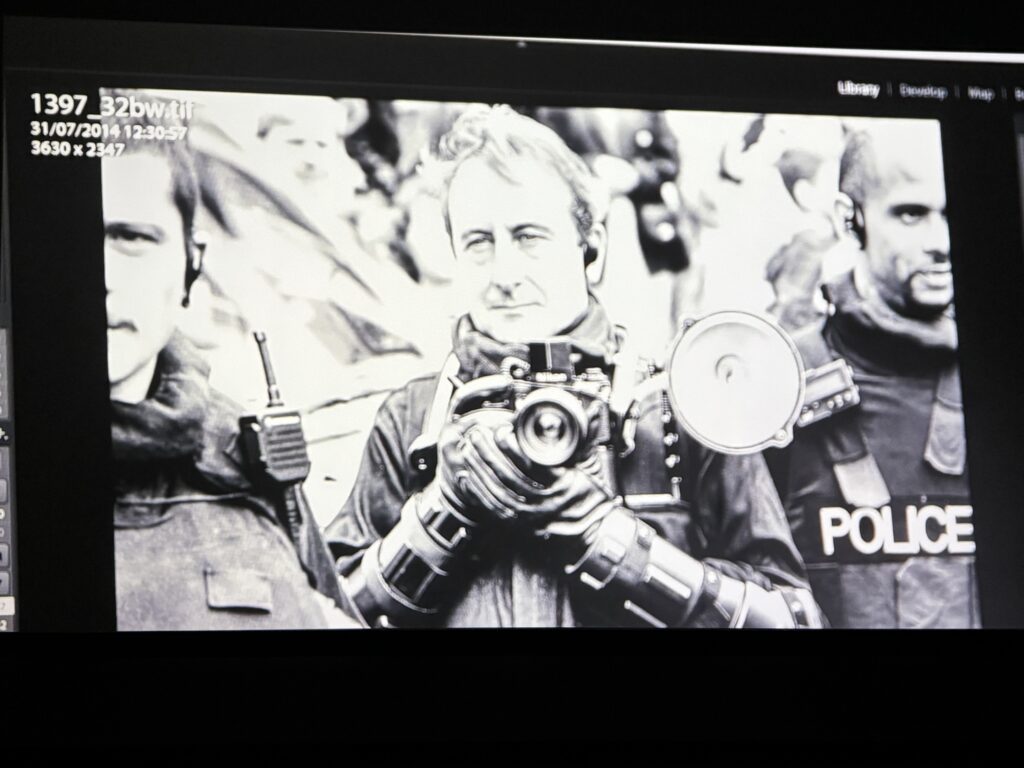

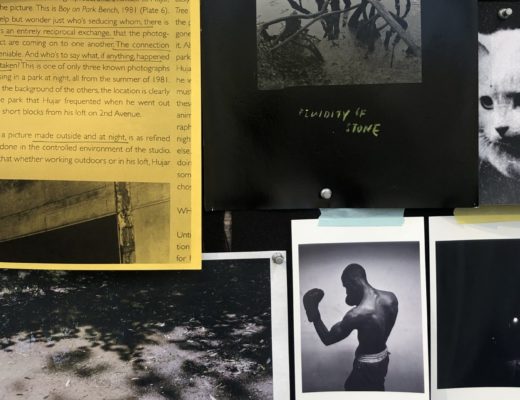

I liked Daniel Ward’s film, Lonesome Ghosts. It made me very depressed. I was experiencing intense police paranoia at the time and watching an hour-long video about the destructive force of state surveillance on political activism wasn’t great for my state of mind. The film’s opening sequence is a dynamite riff on Chris Marker’s repetitive looping as the same footage is repeated three times: first, with no sound; second, with a voiceover explanation that the footage is of a 1979 funeral procession for Blair Peach, a teacher killed by police at a National Front protest; the final loop reveals that the footage was shot by an undercover counterinsurgency unit of the London Met. After this revelation, Ward’s film moves to interviews with various political activists, all of which centre on the corrosive force of police surveillance and infiltration to activist groups. Harrowing, but necessary.

(Crystal)

Bianca Hlywa, Mute Track – St Chad’s Project Space, London

An old garage within a former ear, nose and throat hospital, now lived in by property guardians, felt like pretty much the perfect place for Bianca Hlywa’s deftly brilliant 2025 solo show, Mute Track. On the rainy February of my visit, St Chad’s Projects was cold and damp and hard to find. It didn’t feel healthy. What I always love about Bianca’s work is the sustained subtle questioning of agential relations: between living matter and the machine, between bacteria and yeast, but also between the artist and the material. For, while most people manipulate SCOBY in the service of Kombucha or sourdough, it really feels like, for Hlywa, the SCOBY itself took control long ago. I wrote about Bianca’s solo exhibition on The Penitent Review back in February. Check out the full piece.

(Tom)

Cristina de Middel, Journey to the Centre of the Earth – International Centre for the Image, Dublin

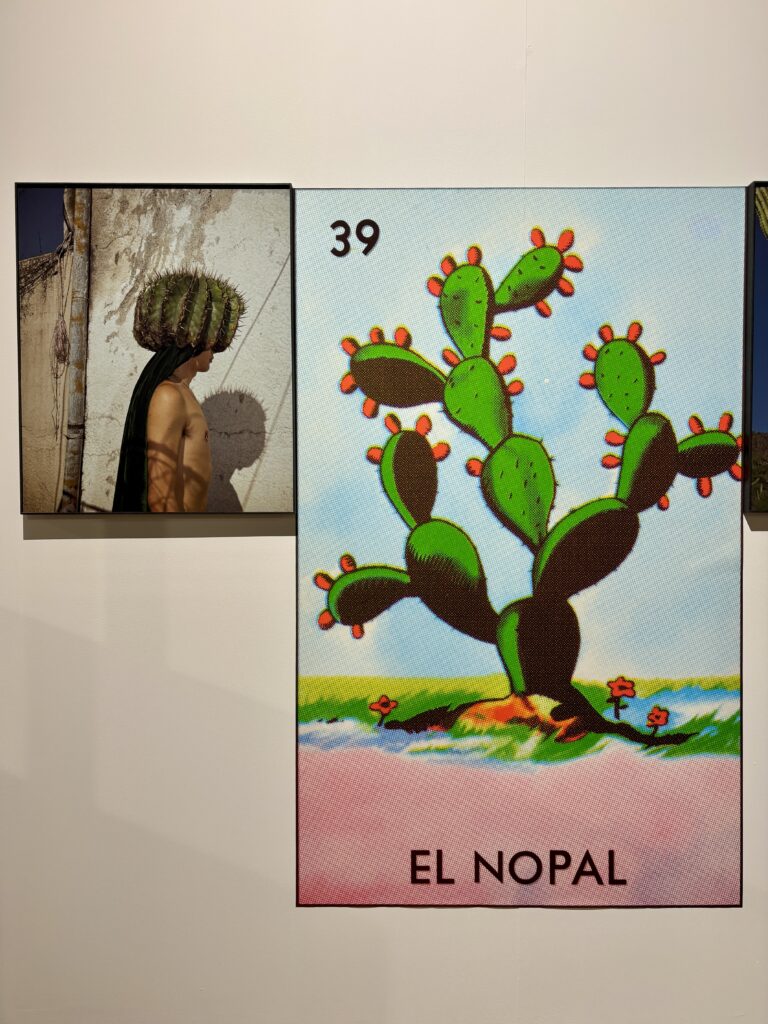

De Middel cites Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth as a key reference for this project, which purports to reframe narratives of migrant journeys between Mexico and California as courageous and heroic rather than (in her words) cowardly. Although the Verne reference feels absent and the reframing not entirely successful, I still found the exhibition moving and even delightful in parts, particularly the witty resonances that emerged from the juxtaposition of De Middel’s photos with symbolic images on Mexican Lotería cards. One such moment: two images of the U.S. border wall are mounted on a wooden scaffold painted to match the border wall’s russet tones. In one photo, an oval mirror leaning against the border wall reflects a stately saguaro cactus. Just visible through the scaffold is a large print of the el nopal (prickly pear) Lotería card, next to a striking photograph of a shirtless young man, a black velvet veil cascading down his back, and a large barrel cactus hat obscuring most of his face.

(Crystal)

Hanna Rochereau – Hauser & Wirth Invites, Paris

Sometimes an exhibition is exactly what you’re in the mood for. Along with half the art world, I’ve had a serious thing for museum storage and the aesthetics of display for a fair while now, and, if her Paris solo show was anything to go by, then Hanna Rochereau does too. In the centre of the gallery stood a gently absurd structure made from glass-topped vitrines, little wooden tables and chests of drawers, upon which perched velvet-lined jewellery boxes and other paraphernalia of luxury display – as if the Liberty’s jewellery department had been remixed by Gerrit Rietveld. On the walls hung a series of acrylic paintings in tasteful greys and beige showing shelving units, filing systems, and stacks of neatly labelled boxes. With all specificity removed, you’re left to deal with forms over contents, structure over meaning. What would you call an unboxing video in which nothing is ever opened? Was it Derrida who wrote that literature is the institution which keeps its secrets? This is an exhibition that finds satisfaction in the deferral of satisfaction, of promises unfulfilled. And yes, that speaks to me.

(Tom)

Azzedine Saleck, The Border that Crossed Me – Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast

Belfast tends to attract artists interested in certain subjects and little surprise that Azzedine Saleck came to the city to make work about borders. A point of difference is Saleck’s linking together of Belfast’s so-called Peace Walls with four other border sites around the world. His multi-screen video installation brings together images of these border walls with poetic texts created in workshops by local young people whose lives are structured around separation and division. Most captivating was Saleck’s pair of patterned carpets, embellished with figurative groups in gold leaf. Suspended in the rug’s central panel, ambiguous and roughly drawn, they suggest men sitting together talking – outside a cafe, on a small ship, in the back of a truck. Here, the gold leaf doesn’t read as a symbol of luxury; to me, it calls to mind the mylar heat blankets distributed to people after surviving sea crossings. Beautiful and devastating.

(Crystal)

Image credits from top. All images TPR unless otherwise stated:

1. Detail, Mario Sergio Alvarez’s De Tuin (2023) and detail, Beya Gille Gacha’s Hands (2021-2023)

2. Hessam Samavatian (2023) Untitled. High-fired ceramic, photosensitive emulsion, analog photographic process. Via Ab-Anbar

3 Cihad Caner, (Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghosti (2025)

4. Installation views of Ayla Dmyterko at Alma Pearl

5. Details from The Ládjogahpir—The Foremothers´ Hat of Pride, Outi Pieski and Eeva-Kristiina Nylander (2018-2023)

6. 1000 Pounds will Save Us; Ikhras; Akil Scafe Smith & Alia Mosallam at Cafe Oto. Video screenshots via Bint Mbareh

7. Noor Abed and Haig Aivazian, ‘Nothing will remain other than the thorn lodged in the throat of this world’. Performance at The Common Guild, Glasgow (25 September, 2025). Photo: Alan Dimmick. Via The Common Guild

8. Detail, proxy protest tool kit, Arjun Harrison-Mann, Benjamin Redgrave and Kaiya Waerea, and installation view Design and Disability

9. Details of The Park (Dancing on the Rubble of Empire), Arwa Aburawa and Turab Shah (2025)

10. Installation view, Hilton Als, Jean Rhys in the Modern World, and Hurvin Anderson, Untitled (2025)

11. Andy Goldsworthy, Oak Passage (2025) and Ferns (2025); Andy Goldsworthy, Wool Runner (2025). Via National Galleries of Scotland

12. Still from Daniel Ward, Lonesome Ghosts (2025)

13. Bianca Hlywa, ‘Mute Track’ at St Chad’s, London. Via the artist

14. Installation view, Cristina de Middel, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and detail of A man wears a cactus helmet in a rooftop in Mexico City. Mexico. April 10, 2021.

15. Hanna Rochereau at Hauser & Wirth Paris. Installation shot via Hauser & Wirth

16. Installation view of Azzedine Saleck, The Border that Crossed Me (2025)

No Comments