Venice! Here we are, back in the land of crumbling palazzos and city-scale cruise ships, gathering for the biennale alongside the most entitled people in the world.

CRYSTAL: The central exhibition has been curated by Adriano Pedrosa and it’s called Foreigners Everywhere. Before it even opened, Anish Kapoor was complaining that the words echo the language of nationalist neo-fascism. I don’t love the title either, but I struggled more with the relationships between the rhetorical framing and its realisation as an exhibition.

TOM: Am I about to agree with Anish Kapoor? If you’re Adriano Pedrosa, your title is speaking to your international art world peers, and that’s fine I guess. But, for people living in Venice, where tourism is a nightmare, plastering ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ all over the city is only likely to emphasise an existing sense of division between local people and the oligarch-simp art world douchebags who pitch up every couple of years and treat the city like a giant yacht.

CRYSTAL: In one interview Pedrosa even described Venice as a city of foreigners! Anti-colonial practice isn’t meant to involve erasure of local populations, but I guess it’s ok if it’s global art-world people enacting the erasure… This signifies probably my overarching issue with Pedrosa’s exhibition. There’s a chasm between the rhetoric of decolonisation used everywhere—not least in the self-congratulatory overemphasis of Pedrosa as the first openly queer curator and the second from the Global South—and the exhibition’s obsession with expanding the canon.

TOM: Uh oh, beware the canon-expanders when Crystal’s about!

CRYSTAL: I wrote about this before in my Katy Hesell review, but ‘expanding the canon’ isn’t a decolonial project. How can it be when, as art historian Maura Reilly puts it, “revising the canon to address the neglect of women and/or minority artists is fundamentally an impossible project because such revision does not grapple with the terms that created that neglect in the first place”? If you aren’t simultaneously dismantling the structures which facilitated canon creation in the first place, expanding representation alone isn’t going to cut it. Black feminists are the sharpest observers of this phenomenon. Just before we came to Venice, I watched a clip of Professor Ruha Benjamin give a blinding address at Spelman College, talking about how neither Blackness nor womanness are trustworthy in and of themselves, but especially not if those identities allow themselves to be “conscripted into positions of power that maintain the oppressive status quo”. I thought about that a lot walking around Venice this year, especially given the context of the genocide in Gaza. Also, it’s just weird to me to describe indigenous people as “foreigners”.

TOM: With something like the biennale, if what you’re doing as a curator is choosing which things go in which rooms, it’s probably a mistake to make sweeping claims about radical systemic change. That said, shall we talk about the work?

CRYSTAL: Yes, let’s! What was your first impression of the Giardini main exhibition?

TOM: Well my very first impression was, oh look, it’s a dome-shaped fabric yurt-type structure and I’ve seen about a billion of those in the last few years. But I have a soft spot for soft furnishings and a tent in a gallery is always better than actual camping. Then, it goes straight from there into a salon-hang exhibition about abstraction from the Global South. Initially, having not read all that much about the curator’s approach in advance, I was like what the fuck is this – the RA Summer Show?

CRYSTAL: I knew about the “nucleo storico” concept, so I was prepared, but yeah, those aspects link pretty directly to my reservations about the project of expanding the canon. And they didn’t feel well-integrated into the rest of the exhibition, so you had these strange pockets riffing on a museum show with exclusively historical work and it all just felt disconnected from the rest of the exhibition.

TOM: In terms of pacing, though, I liked it. Like a novel in fragments rather than a harmonious single narrative. You piece together the connections yourself. I think we both felt that the overall Giardini main show was pretty solid. Noticeably low on spectacle.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, I would broadly agree with that. Afterwards, we chatted about how this was probably the most comfortable, undemanding and unchallenging Giardini show that we’d experienced in Venice. There wasn’t anything mind-meltingly aggravating, but there wasn’t anything that I fell in love with either. Did anything especially stand out for you?

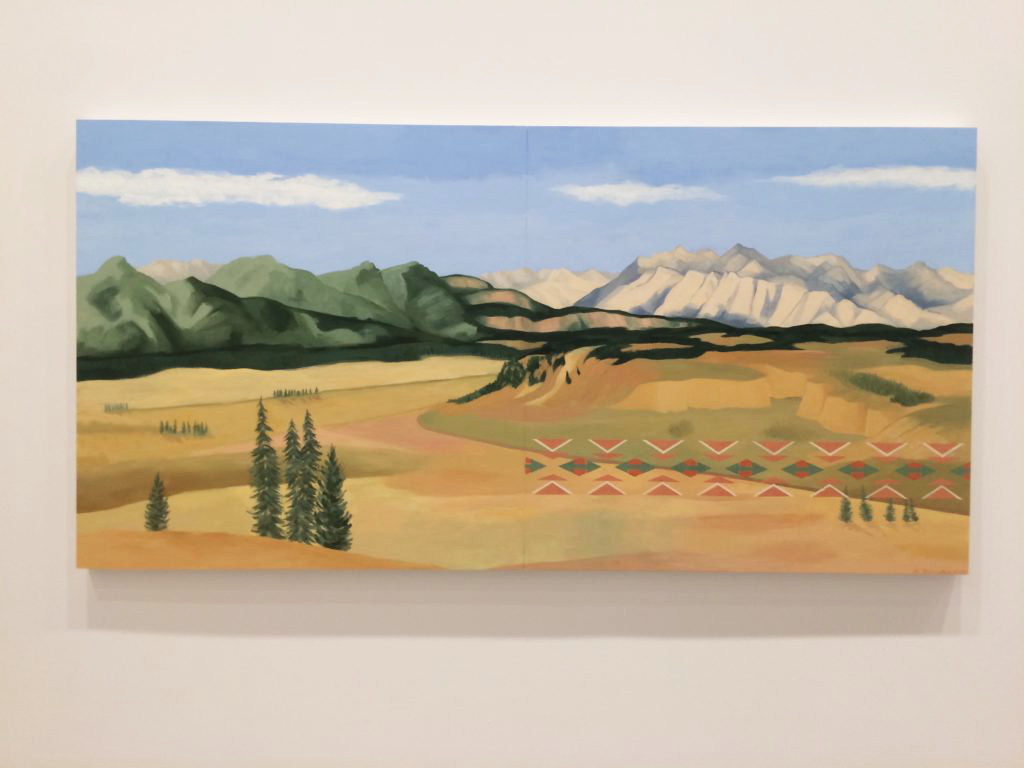

TOM: There were a few things I liked. A room given over to landscape painting worked well. On one wall, Aref el Rayess was like if Carol Rhodes had been born in a desert. Opposite those were Kay Walkstick’s paintings which superimposed abstract Cherokee designs over flattened images of classically rugged American landscapes – one tradition over another in a gesture of reclamation perhaps. It reminded me of William Cronon’s classic essay, The Trouble with Wilderness from 1995, which I return to a lot. He places the founding of America’s national parks within the context of the violent colonisation of Indigenous peoples and the exclusion from land which they had lived in for generations. Nature reserves as part of a colonial project. See also Israel or WWF. And I think Walkingstick’s works challenge these a-historical eco-colonial narratives pretty effectively.

Then, over to the right were Leopold Strobl’s works – a row of tiny weird little coloured pencil drawings on newsprint, with dark amorphous shapes obscuring the figures. That was a strong pairing I thought, Walkingstick and Strobl, that spoke of the erasure of people, especially Indigenous people or working people, in Western histories of landscape aesthetics.

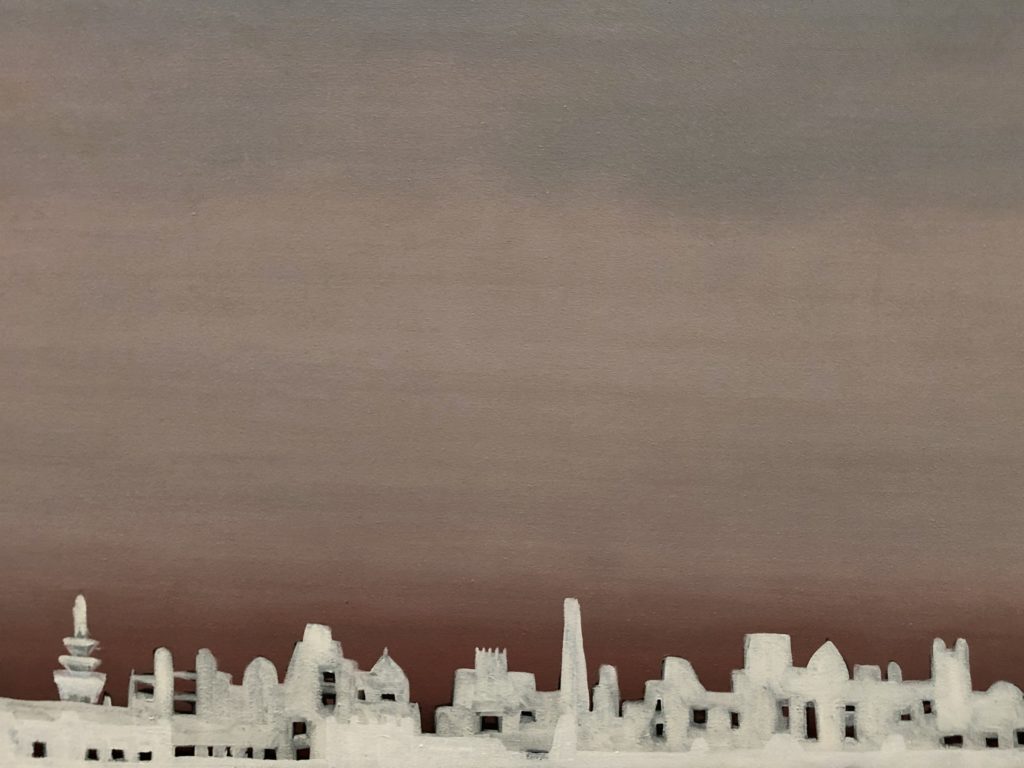

CRYSTAL: There was an intriguing quality about el Rayess’s paintings for sure. Some of the more sci-fi pictures were too cheesy for me, but I did like the first piece in the Deserts series, a quite beautiful abstracted townscape in stodgy white paint across a sweep of plum, lavender and blue sky.

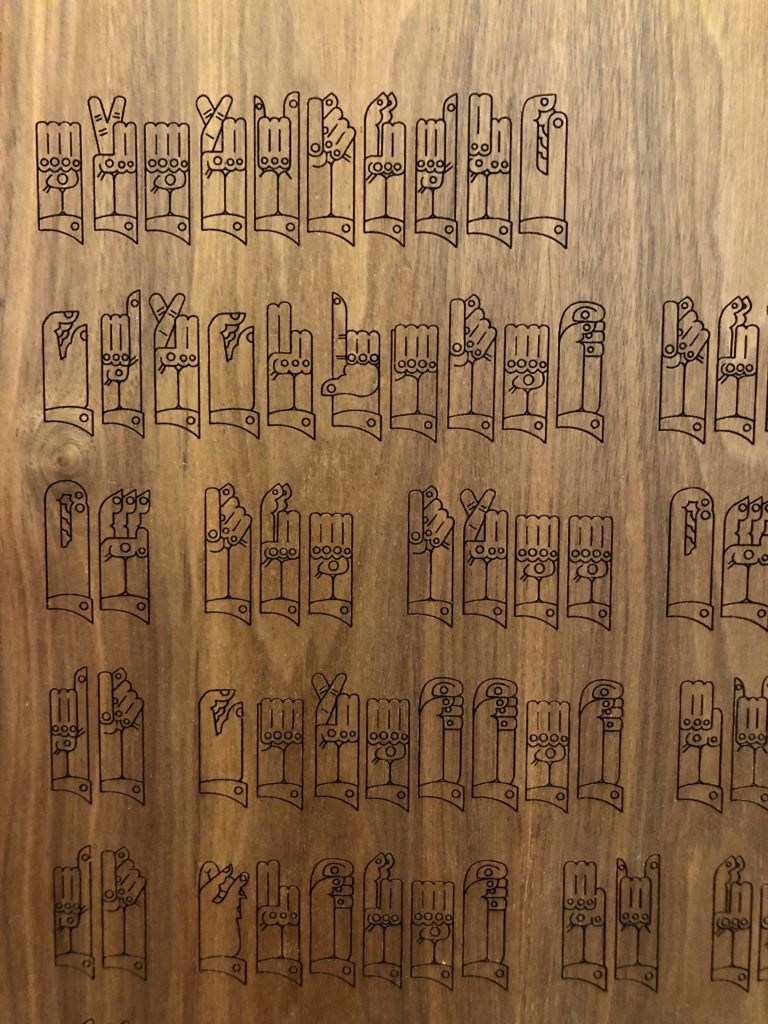

But the work I most enjoyed in the Giardini was Kang Seung Lee’s installation Untitled (Constellations), paying homage to artists who died of Aids-related illnesses and reflecting on the intergenerational care required to preserve queer legacies. I missed Lee’s video in the Arsenale, but these fragile assemblages of parchment, pencil, gold embroidery were s-t-u-n-n-i-n-g, not to mention visually refreshing amongst all the painting and textile pieces. I especially loved Lee’s use of the hand-shaped letters that Martin Wong devised for his paintings, though I personally would have appreciated more clarity in the captions and explicit crediting of the different elements appropriated and remixed from each of the artists Lee is drawing inspiration from.

TOM: Yeah, I mean that whole gallery was drop-dead gorgeous. I might even have gasped as I walked in the room. But then I got all distracted by Romany Eveleigh.

CRYSTAL: The second I saw those paintings, I knew you would love them. Aestheticised, repetitive labour; right up your street. They did nothing for me, but then I read Ben Eastham’s e-flux review where he connects Eveleigh’s paintings to a bit in Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women about why Rousseau thinks women are intellectually inferior, which is all about a little girl who writes O’s over and over again, and how Boyer argues that these O’s are in fact the girl’s secret language, and it almost made me fall in love with the paintings. “Revolutionary letters in the code of Os”. I certainly fell in love with the review. Sometimes, words just give me more than paintings.

TOM: Bloody Ben Eastham writing a way better response to those works than I ever could! It’s funny though, where Ben read them as code (implying a hidden meaning – or rather, a proliferation of hidden meanings), I was more interested in thinking of them as asemic (i.e. with no referential signification). I was also more thinking about the process – the countless hours of making, the rhythm of it, the marking of time with the same mark over and over, or nearly the same, and how change emerges through repetition. Thinking of artists like Pierrette Bloch, who I just love. But also the technique, because from what it looks like, there is a layer of ink applied to the paper, then a layer of pale paint over the top, and then each tiny O is scratched into the surface paint to reveal the dark blue behind. So this is not quite writing but etching. There is a process of excavation, of revealing, but only at the level of a surface, which is no longer just a surface. But yeah, you’re right: Ben’s response is better!

CRYSTAL: So good! I was also intrigued by Pablo Delano’s The Museum of the Old Colony, a large installation of photographic archival material looking at histories of Spanish and US colonial activities in Puerto Rico. Delano calls his installations “anti-museums” or “performative museums”, and I get the desire to force visitors to confront the reality of colonial domination and its violences. But I personally gravitate towards practices that refuse to re-present harmful or violent material and instead engage with archives in ways that explore concealment and obfuscation. I don’t think Delano’s approach quite aligns with my own interests, but I still found his installation compelling. I spent a lot of time with his work.

TOM: In contrast to the Giardini, the Arsenale show was much more about spectacle, about Instagram moments, all that. And the thematic framing did feel like it was running out of steam.

CRYSTAL: That last room, what even was that!

TOM: I know, right. Like maybe a bunch of works just never arrived?

CRYSTAL: I definitely found the Arsenale exhibition a bit more frustrating. I love textile work, I really do, and especially loved the embroidered canvas piece by Bordadoras de Isla Negra (the cows! so cute!), but I was just completely overloaded with textile work after a while. And there were a few pieces in here that I was so not into. Bárbara Sánchez-Kane’s soldiers impaled on a pole, lingerie showing behind their uniforms, were, just, I don’t know what, a terrible metaphor for fragile masculinity in the military. Not a fan. What did you like?

TOM: Well, one thing I really liked, which I’ve never noticed at Venice before, was that all the wall texts were credited to individual writers, rather than some monolithic Voice of the Biennale (played by Brian Blessed) or an assumed ventroliquisation of the curator. Most of the ones I looked up later were art historians.

I liked the cluster of constellation-like paintings on bark by Naminapu Maymuru-White. I know you thought they were similar to the Eveleigh works but I enjoyed how something superficially similar could have emerged out of a completely different cultural context and aesthetic tradition. The idea of the constellation was a running motif through exhibitions actually. I kept thinking of that thing Gilles Clement wrote – how knowledge is not a pyramid but a constellation. I also liked Dana Awartani’s huge installation of hanging silks in tones like saffron and marigold. Up close you could see that these had been torn and painstakingly stitched back together in reference to destruction of sites in Palestine and other places in the Arab world.

CRYSTAL: There’s a beautiful idea at the heart of that work, but I’ve seen so many mended textile works as metaphors for repair that I struggle to find them meaningful.

TOM: Yeah, it is a common gesture but it’s one I find myself drawn to. In Venice, Majd Abdel Hamid had done something similar at a smaller scale for Solidarity is not a Metaphor, an exhibition curated by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, which we can come back to in a bit.

CRYSTAL: What did you think about Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project? I had mixed feelings. It’s a video installation work in which people narrate their migration journeys around or across the Mediterranean area. The videos feature the hands and voices of the people as they trace their paths across maps, their faces unseen. Visually, it’s compelling and the concept is accessible, but there was something that bothered me about the work, maybe an unease at the repetition of ‘good migrant’ narratives. Borders should be abolished and movement should be free, regardless of whether or not the people moving are ‘good’ or ‘assimilationist’ or whatever.

TOM: Yeah there was something weird about this work. For me, it was like politicians, media and government agencies already reductively define people as “migrants” (as if wanting/needing to move for whatever reason is their defining characteristic as people) and I felt the work retrod that logic, by only allowing people to speak about this one experience in their lives. They are given no opportunity to speak on any other subject. After the videos, these journeys have been transformed into constellation-like maps with places like “Tunis – Naples – Marseilles” or “Annaba – Milan – Marseilles” instead of star names. I get that this created a sense of celebration around migration narratives but I also found myself wondering: what is happening when you can abstract somebody’s life experiences to such an extent that they can be converted into diagrammatic maps in this way? How much is being lost when you do that?

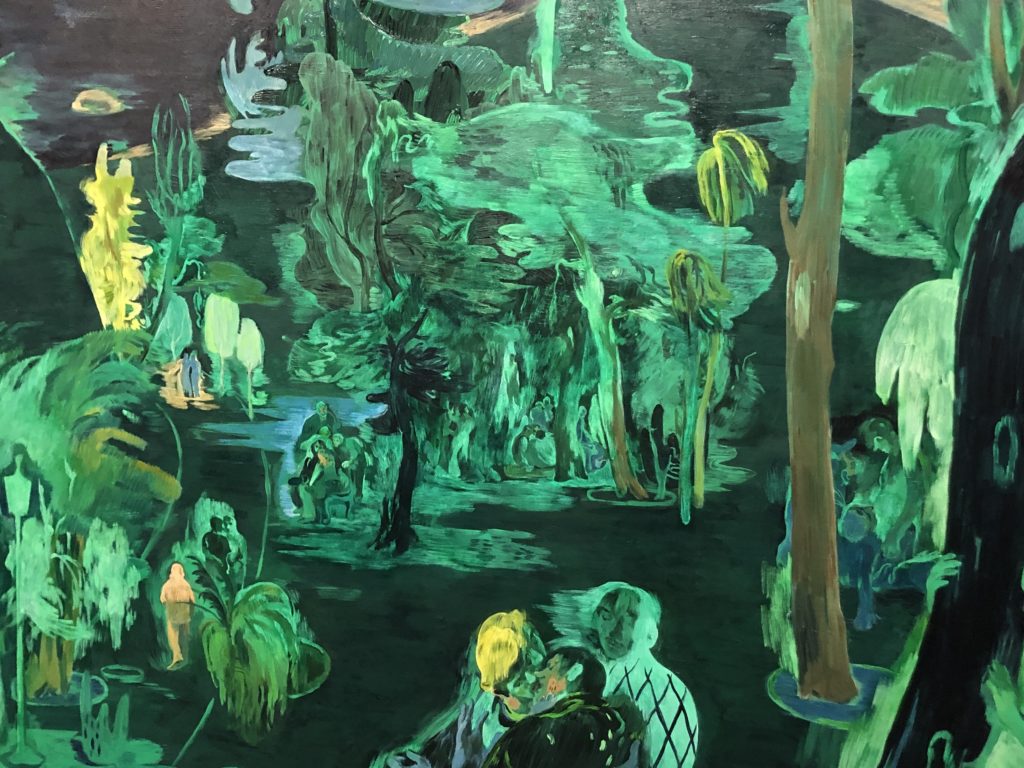

CRYSTAL: Agreed. I kept coming back to the problems of the theme, foreigners everywhere, and how often both artists and subjects felt reduced, abstracted, essentialised, even, their identities simplified down to outsiders, migrants or foreigners, instead of people navigating complex identities in complex contexts. I did still enjoy looking at quite a few things in the Arsenale—the way Dalton Paula paints suits and the way Salman Toor uses green…

TOM: Oh I loved the Salman Toor paintings!

CRYSTAL: I also really enjoyed watching films in the Disobedience Archive, an archive curated by Marco Scotini of works by artists across the world who use documentary and art to speak on political issues. I watched a lot of Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett’s B.A.T.A.M (Bila Anda Tiba Anda Menyesal) – When You Arrive You’ll Regret, an exploration of Batam Island in the Riau Archipelago and different ways of crossing Singapore’s borders outside of official channels, which was great. But it was also 45 minutes long, and there were I think 39 other films. It is just completely impossible to watch all that! I’d like someone to put on a show just with films from the DA, like that recent Raven Row show about DIY television from the 1970s. That would be amazing.

TOM: Anna Zemánková’s mixed media embroidered drawings of floral patterns were glorious, I thought. And it was great to see work by Nour Jaouda – I covered her exhibition at Union Pacific last year, which was incredible – poetic, situated, melancholic, materially intricate and considered. Her hand-dyed textile pieces looked great here and titling all three works with lines from Mahmoud Darwish felt like both an important acknowledgement of influence and a statement of solidarity.

CRYSTAL: Visually, I really struggled to see what you see in those works. I wish I liked more of the work here in general.

TOM: To be honest, probably the most memorable thing that we experienced at the biennale was the ANGA protest against the Israeli genocide pavilion.

CRYSTAL: Absolutely. The protest had been in the planning for weeks, following ANGA’s campaign signed by thousands, calling for the Israel pavilion to be withdrawn from the Biennale. It was especially interesting given that the artist, Ruth Patir, announced the closure of the pavilion the day before, which completely dominated early press coverage. It was pretty obviously a disingenuous media stunt, considering that a huge screen showing a video of her work was still viewable through the pavilion windows. It was weird going around the Giardini exhibition in the morning with a keffiyeh wrapped around my waist. We were clearly overly paranoid about the bag searches.

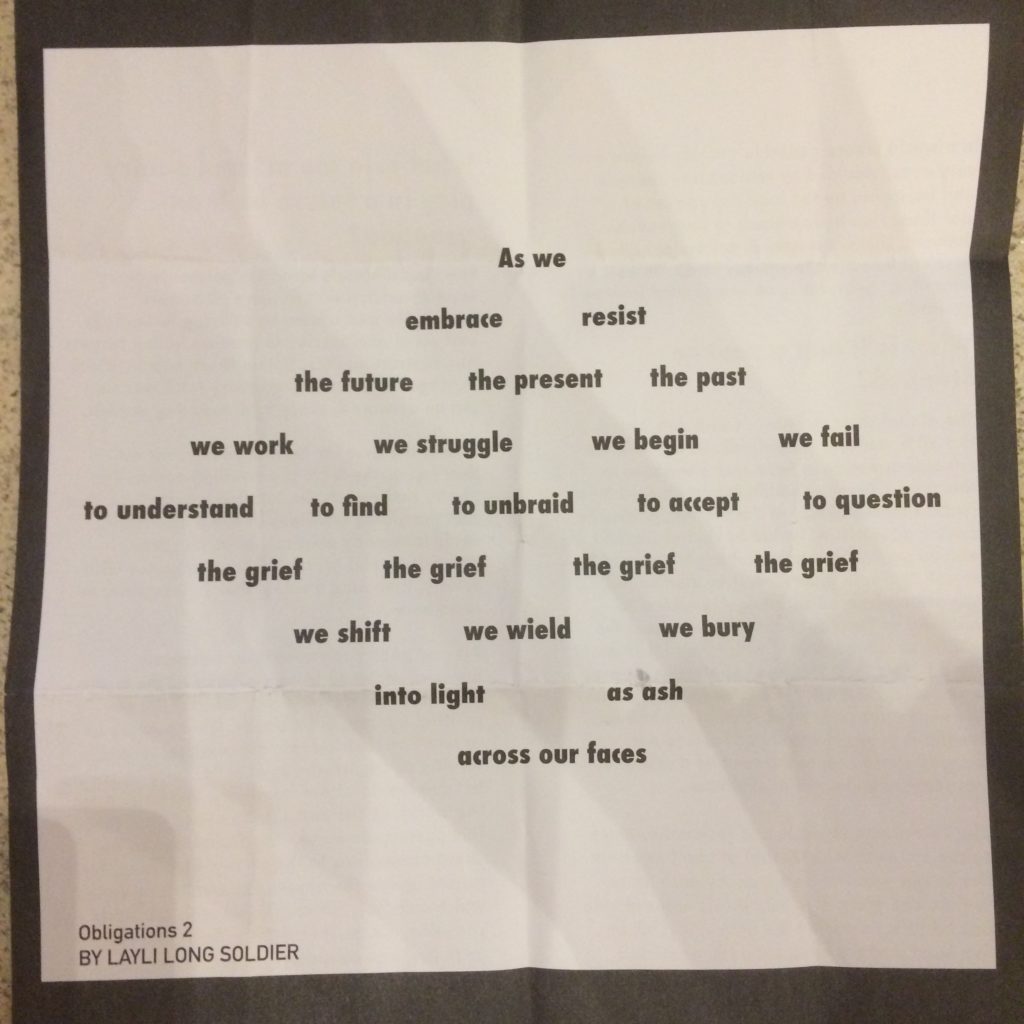

TOM: Given the calls from a few people to boycott the entire biennale, I wasn’t sure whether we should come to Venice at all. But knowing that there was an action taking place felt important. Seeing people actually giving a shit and willing to take a risk felt genuinely inspiring. The speeches were so great, and the reading of that poem – Obligations 2 by Layli Long Soldier – just had me in pieces.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, as much as parts of the art world are rife with idiotic, posturing dickheads and enraging institutional politics, when you find community with other artists and art workers organising politically, it’s incredibly grounding. I don’t think I’ve ever felt that at a Venice Biennale before, but I felt it this year. I also loved the ANGA protest pamphlet that was dotted around the Giardini, which had a map of pavilions complicit in genocide. We boycotted the genocide pavilion, obviously, as well as Germany and the US.

TOM: We also boycotted the UK and France, but that was as much to do with the length of the queues as complicity. There were loads of other Palestine exhibitions and events around town, which we’ll come back to. Palestine featured subtly in the Spanish pavilion too. That was probably our fav pavilion in the Giardini, right?

CRYSTAL: Yeah, I really enjoyed Sandra Gamarra’s work. Again, there are many examples of this kind of work, a reconfiguring or rewriting of European pictorial heritage—Spanish in this case, in relation to Gamarra’s Peruvian heritage—to make silenced cultures and peoples visible, but nevertheless, the overall effect, especially of the first three rooms, was really striking.

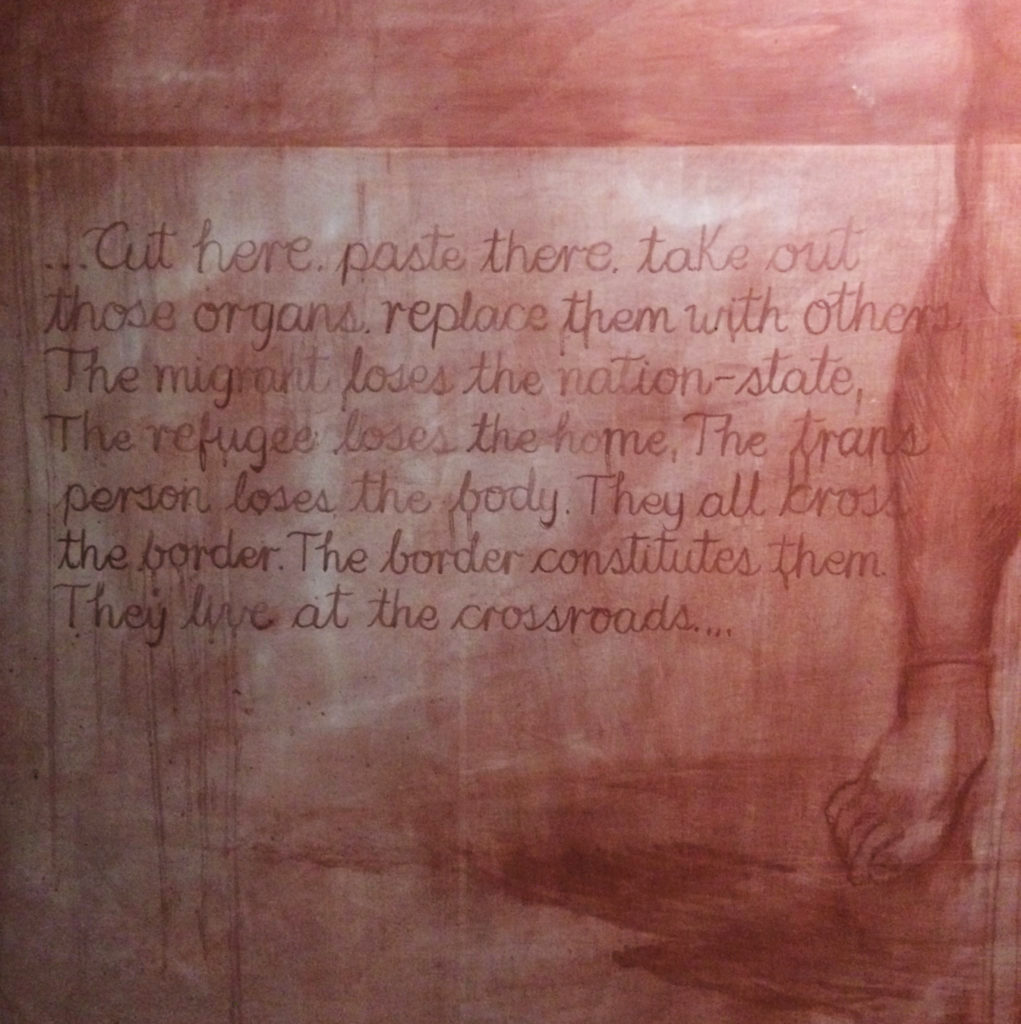

TOM: I really liked the massive painting that included two quotations from Paul B Preciado’s incredible Can the Monster Speak? One being: “…the trans body is to normative heterosexuality what Palestine is to the west: a colony whose extension and form is perpetuated only through violence…”

CRYSTAL: You know how much I love text in art and I enjoyed the first room of paintings on the idea of terra nullius and the use of landscape painting as a representational tool to argue for colonial ownership of land through agricultural improvements. But Extinción II (Illustración botánica con manos) was my favourite work in the pavilion. Disembodied hands painted over facsimile pages from an 18th-century botanical expedition manual. Something about those floating hands and their gestures felt like a powerful counterpoint to the taxonomic violence of the colonial botanical specimens. I really loved those pieces.

TOM: You seem to be enjoying disembodied hand gestures a lot right now!

CRYSTAL: Ha. Yeah, true. What can I say, I find the semiotics of gesture fascinating. Otherwise, most of the national pavilions in the Giardini or Arsenale didn’t really resonate. I usually love the exhibitions in the Greek pavilion, but it didn’t connect for me this year. Sonic landscapes and an agricultural watering hose ballet. The text spoke of village festivals and agricultural time cycles, but I think they abstracted too far and stripped out too much of the liveliness of festival culture. Maybe the idea was that the audience ‘performed’ some of that energy, but I don’t think it worked for me, partly because an audience of Biennale opening-week visitors doesn’t give me community feels.

TOM: I dunno. I kind of liked the steampunk infrastructure vibes.

CRYSTAL: Austria did my head in. I thought I wrote the text down but I can’t find it.

TOM: Luckily, I did write it down! And I can even read my writing. It described the ballet dancers as “rehearsing for regime change in Russia”.

CRYSTAL What does that even mean, rehearsing for regime change? You’re either working to make it happen or you aren’t, right? It was a fairly uninspired film of ballet dancers. I did not like this at all.

TOM: I mean flowers and ballet rehearsals are pretty standard things in art history but I thought Anna Jermolaewa did well to breathe a sense of political specificity and power into such tired old motifs. I actually loved that line so…

CRYSTAL: I found it deeply irritating.

TOM: The Poland pavilion was also Ukraine-focused. And maybe again the issue was the opening week audience. The work was supposed to encourage people to ‘sing along’ to films of people mimicking the sounds of war – air-raid sirens, missiles etc. There was something effective in the footage of people using their own voices and mouths to recreate these sounds of mechanised destruction but the karaoke framing didn’t really work.

CRYSTAL: This did nothing for me. I’m looking for work that expands my understanding of something, introduces me to new histories or ideas, seduces me with its aesthetics, or generously offers up a unique, situated perspective from a particular artist in relation to their particular place/s in the universe. Something I felt a lot in the Arsenale in particular is that so many of the artists are presenting experiences in a way that seems weirdly ungrounded. The works presented here don’t seem to bring the specificity of their groundedness into being – like, I was left with very little sense of how a queer artist in India is in a different space from a queer artist in Indonesia or a queer artist in Brazil. Anyway, maybe that’s tangential.

TOM: Or maybe that’s just the Venice effect.

CRYSTAL: Japan also irritated me. Making music with electrified fruit. Fine, but it reminded me of a school science project with better aesthetics. Maybe I’m just easily irritated.

TOM: What about Canada? I wanted to like this as Kapwani Kiwanga showed some great work at Tramway for Glasgow International a while back. I loved the materiality here and up-close the details of the beads were gorgeous but the overall installation didn’t quite work for me. It’s a tough space though, with all that curving glass.

CRYSTAL: Same. I really wanted to like this work, and materially it was beautiful and conceptually strong, but it felt a bit like a set design for a performance that never happened.

TOM: Pretty much half of Venice feels like that sometimes!

CRYSTAL: I also really wanted to like Inuuteq Storch’s work in the Denmark pavilion, both because it’s the first time an Indigenous artist has shown in the pavilion and also because it was a photography project and there was so little photography in general this Biennale. But it felt like a strange mashup of teenage endless summer snaps and a National Geographic spread, and not NG in a deliberate way like Claudia Ruiz Gustafson’s amazing work, La ciudad en las nubes, which appropriates key visual motifs from the mag. But I heard a lot of people talking about how much they loved this, so… The Belgian pavilion was also a little confusing. Giant puppets and people dancing. Also, it wasn’t super clear whether people would be there dancing all of the time or if that was just for the opening. In which case, it was just giant puppets.

TOM: People seemed to be genuinely enjoying themselves though, which is always nice I guess. The Netherlands was a full-on dance party when we pitched up. But that at least made sense, right?

CRYSTAL: Maybe not how you thought at the time, though. Critics are under so much pressure to publish their reviews immediately and one of the reasons I love that we have our own thing is because it means we can take more time to think about what we’ve seen. Also, frankly, to look some shit up. I wasn’t that enamoured with the figurative cocoa sculptures on display here, made by a Congolese artist collective called Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise, billed alongside Dutch artist Renzo Martens. The premise of the pavilion is that sales from sculptural work will fund the purchase of former plantation lands to be replanted as forest. Initially, I thought this work sat in the realm of an artist like Theaster Gates, selling commercially to fund community work. But the more I thought about it, the more I suspected that Martens was more of a Nicholas Negroponte (of one-laptop-per-child fame) character. It turns out that the artists’ collective emerged from a project organised by Martens around the same sort of time he was talking about “gentrifying the Congo” and releasing a film project called “Enjoy Poverty”. Yikes. As Zoé Samudzi points out in her blistering review of Martens’ role in this project, this is an old story in which a Global North artist makes himself seem relevant to current political and social concerns by cultivating artists in the Global South to produce ‘a luxury good for the Global North whose profits trickle back to the Global South, the product and the process this time disguised as “empowering”’.

TOM: Urgh, I hadn’t realised that. You’re right – on the surface it looked like a great project but that’s some proper bullshit.

CRYSTAL: Over in the Arsenale, the Ireland pavilion was refreshingly bonkers. I’d wanted to see this after picking up Eimear Walshe’s pamphlet The Land for the People: The Sexual Case for Land Reform in Ireland last time I was in Dublin. When I looked them up, I clocked that they were representing Ireland at Venice this year. Subject-wise, it’s not the most original—ruins, evictions, land rights—but the treatment was fresh. There was a hypnotic quality to the synthesis of trad, 19th-century rural aesthetics visually clashing with emerald green latexfetish masks coupled with the drone-y vibes of the Gregorian chant narrative overlay. I particularly enjoyed the fact that the film was shot on four beat-up iPhones passed around between the members of the cast.

TOM: Yeah this was great. The smell of the clay seating as well really brought something. My notes though are literally just the lyrics.

O dwelling place beloved

Don’t fall on me too soon

I kept your stones upstanding

They come to make a ruin

The dust is in my belly

The soot is in my lungs

The damp is in my skin

The house has sown its seed in me

And soon when I am dust

Another hand will come

And make me into blocks

And build their home from me

I mean, all I’ve got is a big fat heart symbol next to this, which is not exactly the most incisive critical response.

CRYSTAL: Ha! I genuinely love that.

TOM: What else? Across the city, it was great to see the Palestine collateral project, the Allies + Artists x Hebron exhibition, where Shaima Hamad linked cooking traditions to land and belonging in a really effective way.

CRYSTAL: I love Adam Rouhana’s photographs so much and it was a joy to see one here, quite a well-known photo of a young boy eating a watermelon. I wish there had been more of his images.

TOM: We both really loved the audio work too but I can’t find out who it was by. There was a beautiful line in that: “Isn’t all land holy? Isn’t every structure a temple?” I mean…

CRYSTAL: Yeah, that was beautiful and not enough was made of that piece, I thought.

TOM: In the same building, I was especially keen to visit the Pinchuk show, which had understandably chosen not to go with its usual Future Generation art prize and instead present a show responding to Russia’s full-scale invasion. I found the overall show a bit disappointing, not really showing the Ukrainian artists in the best way and incoherent in its inclusion of certain international names. But this is the approach that curator always takes so I guess I should’ve known what to expect. Otobong Nkanga’s massive tapestry was incredible though and I was super happy to see Anna Zvyagintseva’s work, To plant a stick, IRL after having followed her work for a while.

CRYSTAL: And included it in your Whitechapel walking book!

TOM: Ha, yeah. It’s always a little nerve-wracking when you see a work that you think you’ll love, so it’s kind of a relief when you do. It’s such a beautiful project – from the starting point of a family archive (a scrap of poetry written by the artist’s grandfather) to prompt personal recollections of childhood walks to wider cultural questions around language, identity and resistance, and then, wider still, to cycles of death and renewal. A piece of paper, a black and white photograph, stems of willow resprouting in water: three things that together signify so much.

CRYSTAL: I liked it too, to be fair, but I don’t think the presentation here really showed the work off to its best advantage. What else was good?

TOM: The Solidarity is not a Metaphor exhibition?

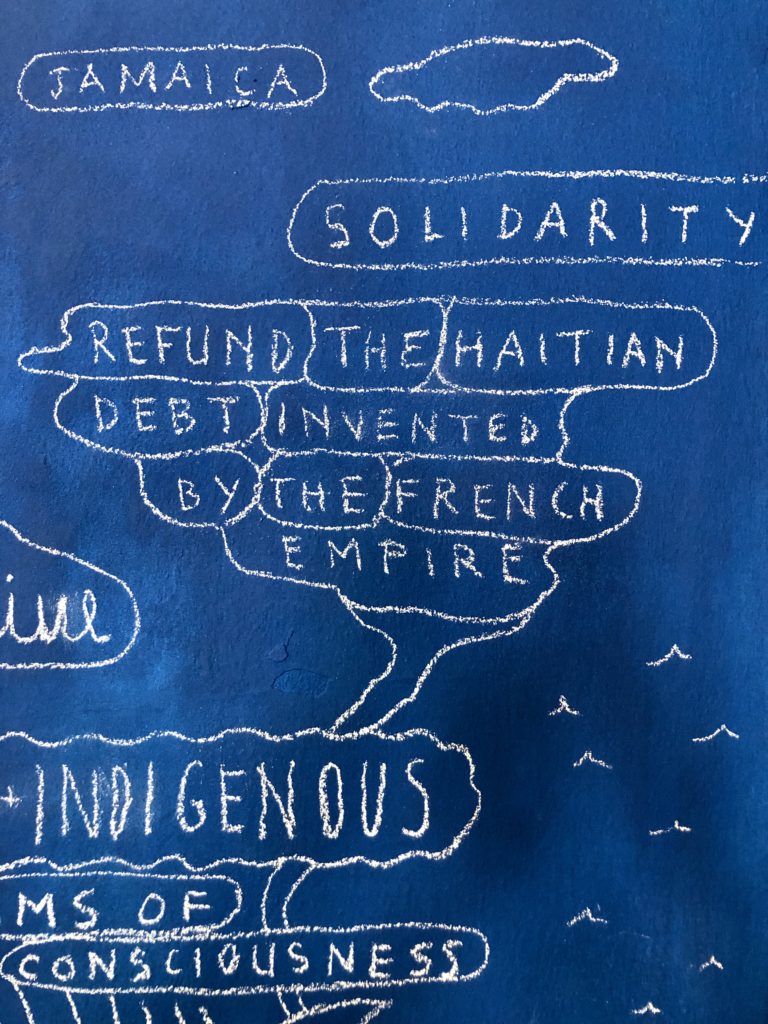

CRYSTAL: Yes! I completely clicked with Olivier Marboeuf’s A Liquid Monument, a chalk-on-ultramarine-blue mural looking at the sea as a site of necropolitics and economic conflict. We visited this pretty early on and there were two lines that immediately jumped out at me on Marboeuf’s mural: “We don’t need Black visibility. We need Black sovereignty”. In a Biennale foregrounding visibility of marginalised artists from the Global South, within a hyper-reductive framing of “foreigners”, I kept coming back to these lines. Visibility is good, representation is important, but sovereignty, power, resources, surely, that’s what it’s really about. I’ve seen a lot of similar mapping murals, doing wake work, as Christina Sharpe calls it, but Marboeuf’s stands out. Sometimes mapping murals are an encounter with facts, facts and more facts, but Marboeuf’s is an unexpected engagement with a truth-telling storyteller. I liked it very much.

TOM: Me too! Another work I really loved in that show – also text-led – was by Yana Bachynska. For me, seeing how different groups respond to Ukraine and Palestine has been both enlightening and hugely depressing. Where I expected to see solidarity there has been so much division. For example, the Western liberal centre responded quickly on Ukraine, issuing statements, cutting financial ties with Russian oligarchs. But then on Palestine they’ve all said “Oh no we can’t possibly do politics, we can’t do cultural programming without genocide money” etc.

CRYSTAL: That hypocrisy has just been so utterly vile.

TOM: Exactly. But then there’s big chunks of the Western left – so well-informed on Palestine and quick to stand up against Israel’s colonial oppression – and yet totally stuck in a Cold War mindset that prevents them from understanding Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in its proper context. All they can comprehend is that if the US supports something, it must be bad, therefore NATO is to blame, it’s really a proxy war, Ukrainians are all Nazis, the incredible popular revolution of 2014 was actually a CIA-backed coup etc. It’s properly batshit.

On the flip side, certain Ukrainian leftists in the art world who I once admired for their anti-fascist work have been truly embarrassing on Palestine. Despite all the claims of universal solidarity, Israel’s genocide has revealed the limitations of these people’s thinking. So quick to wield the language of anti-colonialism, and yet in reality their solidarity only extends as far as other white people. In seeing themselves as defenders of freedom an European “civilisation” they have imbibed its worst values. It’s basically what you were saying earlier about canon expansion. Not pulling down the walls of Fortress Europe – just asking to be let inside.

CRYSTAL: And the art work?

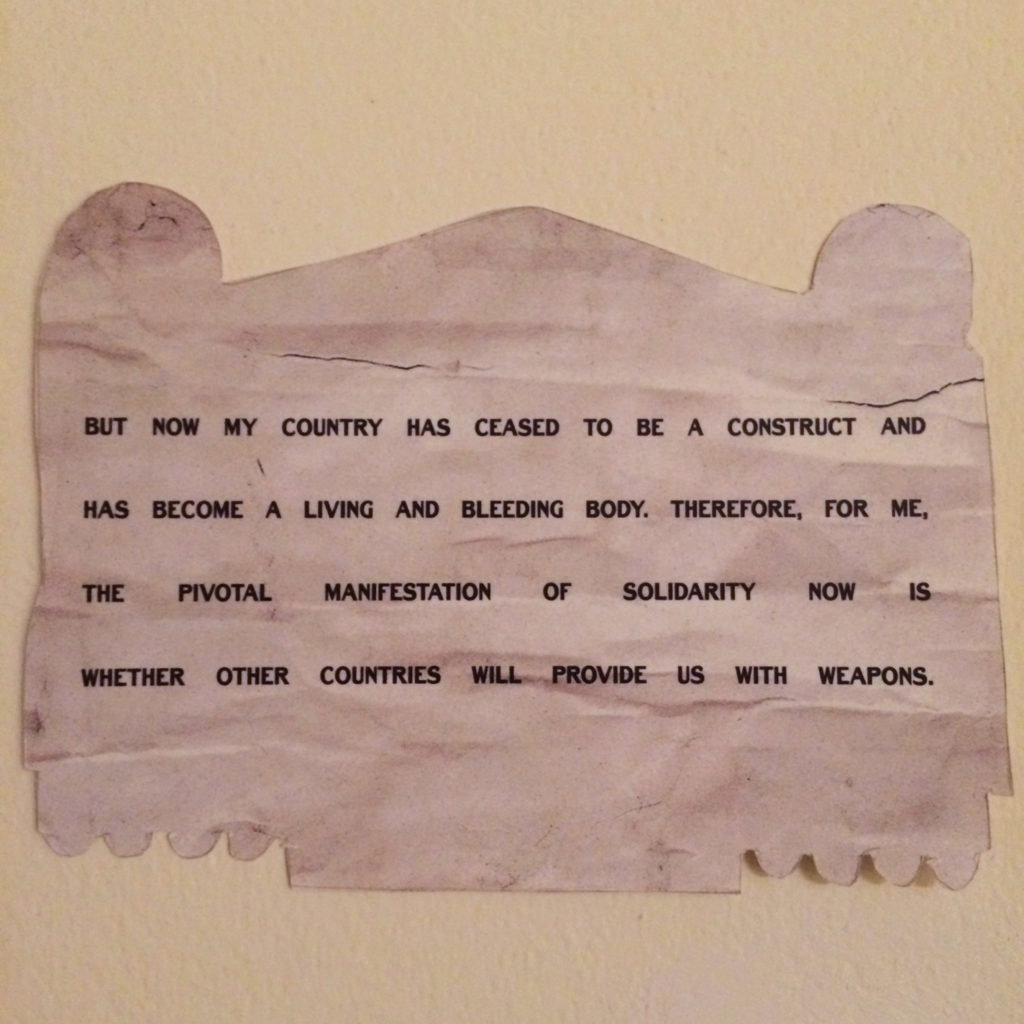

TOM: Oh yeah sorry. All of that is a long-winded way of saying that when I see artists and writers effectively articulating positions that are both pro-Palestine and pro-Ukraine, it makes me emotional. Bachynska’s work does this with such concision it’s breath-taking. A series of textile pieces made from personal clothing and found fabrics are interspersed with texts which form a narrative of sorts:

Until 2022, for me the word solidarity existed mainly in the context of class or gender struggle. I completely rejected Ukrainian or any other national identity.

But now my country has ceased to be a construct and has become a living and bleeding body. Threfore, for me, the pivotal manifestation of solidarity now is whether other countries will provide us with weapons.

Nationalism is a crock of shit and then you’re invaded by Russia. Everything changes. It reminded me of Iryna Zamuruieva’s article a while back: “why we as feminists must lobby for air defence of Ukraine”. Or the chant we’ve all been singing together for so many months now: “When people are occupied, resistance is justified.”

OK, sorry. Rant over, What else?

CRYSTAL: Nebula, I think!

TOM: Oh yeah!

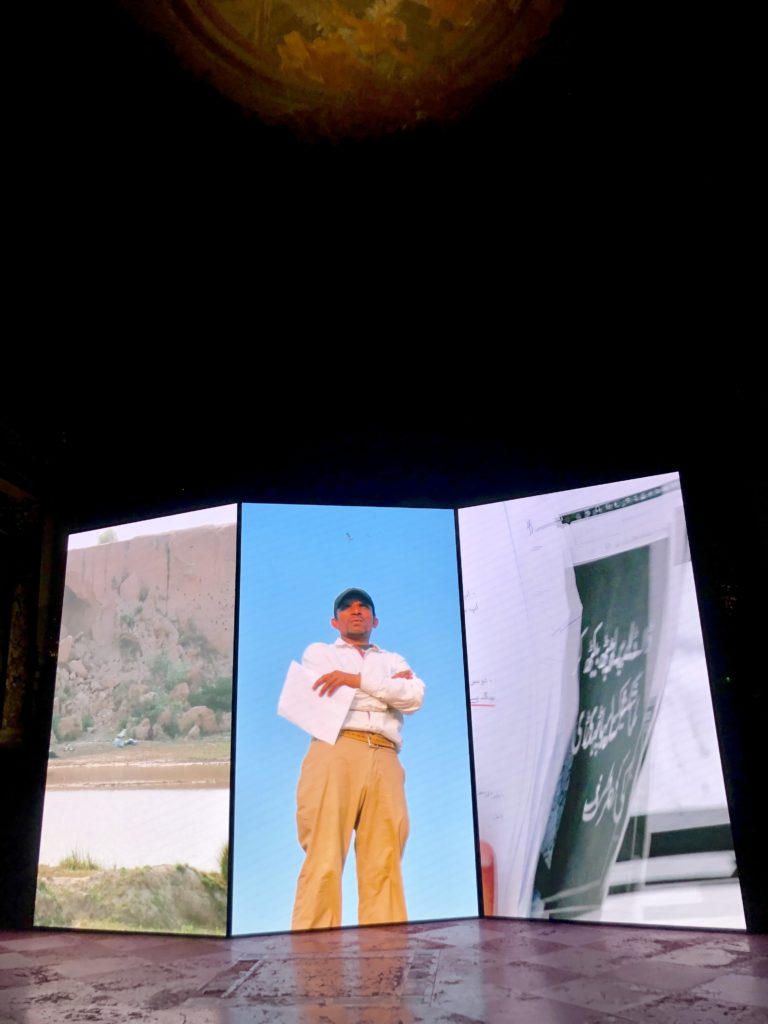

CRYSTAL: With eight different video works commissioned by Fondazione In Between Art Film, in the sprawling former hospital complex, the Complesso dell’Ospedaletto, this was probably my favourite overall exhibition we saw this year. The first work, Basir Mahmood’s Brown Bodies in an Open Landscape Are often Migrating, screened in the hospital’s chapel, was among my favourite pieces in Venice. Shown across three large vertical screens, the film deploys Mahmood’s frequent strategy of working with a film crew from Lahore, to bring us a meta-narrative in which the film crew re-enact scenes from found footage filmed by migrants travelling to Europe—sometimes narrating their journeys, sometimes giving advice to others travelling in their wake.

TOM: I loved this too – and interesting to compare to the Bouchra Khalili piece in the Arsenale.

CRYSTAL: Absolutely! I think Mahmood devised a more beautiful, interesting and ethical representational strategy. The meta-narrative adds complexity, making me think, too, about the often pernicious role of film and photography in perpetuating demonising narratives around migration, and brings a strong sense of the artist’s interpretive voice. This is definitely one of the works, one of the artists, that I’ll continue to think about.

TOM: Agreed. This is a point you’ve made before but the best works in Venice also respond to the context of showing in Venice, and Mahmood’s work did that – the triptych form, the scale and dimensions of it. It had a strong presence within the church architecture of the space. I also enjoyed Christian Nyampeta’s film installation, When Rain Clouds Gather, which tackled subjects like the Rwanda genocide and Palestine, but again with a kind of meta-framing, this time an informal art school crit session. I found the framing less successful than Mahmood’s but it’s a work I’d like to watch again.

CRYSTAL: Same.

TOM: What else? You wouldn’t let us go into the William Kentridge show.

CRYSTAL: I mean, it makes me laugh the way that the collateral exhibitions are always dominated by the same old white dudes, no matter how inclusive the curated programme claims to be.

TOM: As far as boring old white dude artists go though, I quite like William Kentridge.

CRYSTAL: That’s because you’re basic and have no taste.

TOM: True.

CRYSTAL: Cyprus was interesting. Like Greece, this is another pavilion that I normally really enjoy.

TOM: I think we were both here primarily to see Haig’s work, right?

CRYSTAL: Yes! I genuinely think Haig Aivazian is such a brilliant thinker. He has such an exciting way of synthesising different threads, ideas, and histories in a way that really speaks to me on an intellectual level. Hardly a month goes by when I’m not telling someone about his performance lecture on surveillance, sporting events and stadia at Kadist back in 2017.

TOM: World/Anti World: On Seeing Double. I saw that IRL so I guess I win at art.

CRYSTAL: Whatever. Aspects of the film shown here resonated, but it’s difficult to see one part of a bigger project and feel like you’re getting the full Haig experience.

TOM: Yeah, it was the second part in an ongoing animated film series, produced in collaboration with a group of animators in Beirut. The work was a response to a crackdown on queer spaces in Lebanon and of course to what Israel is doing right now in Gaza and the West Bank. I think this approach brings something interesting to Haig’s work – there is a slight blurring together of all the source material so the end result feels more like a harmonious whole. But it was a short piece and Haig is so great that it would have been good to see more. The most powerful moment for me was at the morning media view when the artists read out Palestine Hologram by poet Lisa Suhair Majaj:

In the universe of our dispossession, we scatter:

shimmering holograms, phantasms dispersed

to light, dismissed as mirages by the image makers…

I’d love to see Haig make a work in response to that poem, it chimes with so many of the interests that run through his work. I feel like throughout our time in Venice the most powerful moments were from poetry not visual art. But I’m not sure what that says exactly…

CRYSTAL: I think I’m broadly in agreement with you. That poem in particular was hugely resonant. I’d encourage everyone to read it. Sadly, we then headed to the Prada Foundation. I think I’ve finally decided that I don’t really like Prada Foundation exhibitions. It was only that one time, honest! Maybe it’s that I (mostly) love Salvatore Settis exhibitions. Anyway. Christoph Büchel wins my prize for worst thing this year. Possibly ever. Jesus, it was awful. I don’t know that I want to give it credence by talking too much about it, but it’s obvious that Büchel is enamoured with his own brilliance. Only, he’s an intellectual lightweight, a charlatan with an unlimited expense account. This whole show is nothing more than a fetishised working-class debt and poverty spectacle with bullshit politics. Appropriating the Gaza genocide, represented here through bags of Israeli cement and a LIVE STREAM of Gaza under bombardement, is intolerable. On the way out, I clocked a knowing “D. Graeber” office nameplate on one of the doors coming down the main staircase. Büchel thinks he’s a genius. Frankly, he’s just an asshole.

TOM: By contrast, the Bulgarian pavilion used some of the same aesthetic strategies as Buchel – immersive, hyper-detailed installation – to give a spatial dimension to some grim personal and political histories. It felt situated in a meaningful way.

CRYSTAL: I thought it had an eloquence about it, but it didn’t completely win me over. I appreciated the framing of the work, this idea of the possibilities allowed by art for disseminating research and lived experience about suppressed cultural trauma, but honestly, I wonder if the set dressing of the domestic spaces really added to the audio recordings. I almost wished the room was completely empty.

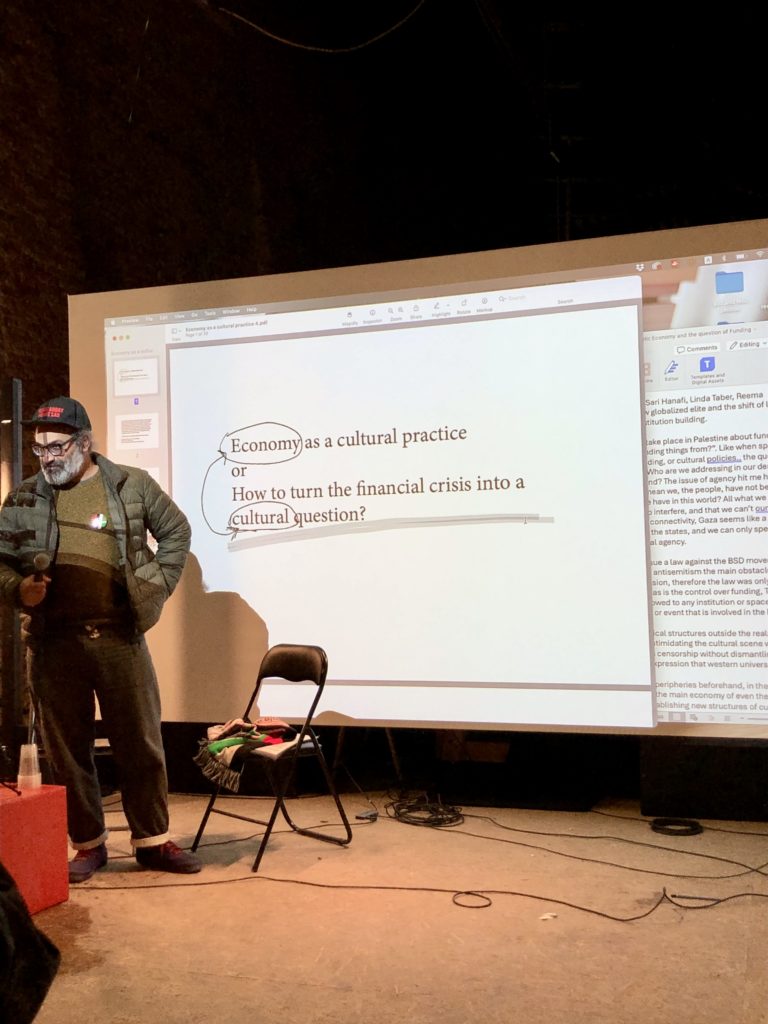

We also went to Yazan Khalili’s talk on Palestine and cultural funding at Sale Docks on Friday night. Sale Docks are an absolutely brilliant collective operating out of an old salt warehouse in Dorsoduro. They had a fab programme of talks and events during the Biennale, alongside an ongoing research on the working conditions of the Biennale and critiquing its relationship to the city. It’s a much-needed corrective to a lot of artworld chat, where I hear more people talk about the fact that Venice is sinking than the impact of tourism on residents. But yeah, Yazan’s talk was brilliant. He talked about making things work at the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre, watching things fall apart a bit at documenta last year, and the funding landscape of trying to work in arts and culture in Palestine. It was great.

TOM: Yeah he spoke particularly about the importance of groundedness – being meaningfully rooted in a community (the total opposite of the biennale despite the illusion created by the in-situ pavilions) – and about the importance of having a ground which is unconnected to the market, that cannot be taken away if you run out of money or have your funding cut. He was super interesting on the phenomenon of NGO-isation, the problem of boards who are not involved in everyday running of arts institutions but still get to make or block important decisions. I liked the way he talked about their work not as institutional critique but as affirmation – acting in response to the question: what do you do when you have the power? After all, as he said, “no funding comes without political demands” and, given the way we’ve seen arts and cultural institutions respond with abyssal silences over Palestine, this has become deafeningly clear.

CRYSTAL: 100%. I wrote that down, too, in my notes: what do you do when you have the power? I think this really brings it back to the point about the difference between representation and structural change in Pedrosa’s exhibition, and the Biennale more generally. Representation is necessary, of course, but if that’s happening in isolation then nothing is ever going to be meaningfully different.

TOM: ❤️