I wasn’t familiar with Edith Dekyndt before I encountered her work in the Bourse de Commerce. English suffers somewhat from a lack of verbs that express ideas connected to knowing. Of course, I knew Dekyndt’s work. I later realised that I had walked through her 2017 dust-sweeping installation at the Venice Biennale. And perhaps I had encountered her still life compositions elsewhere without really seeing them. But until the Bourse, I’d not made a link connecting the artist, her work and her name. These are connections I tend to make with art only on falling in love.

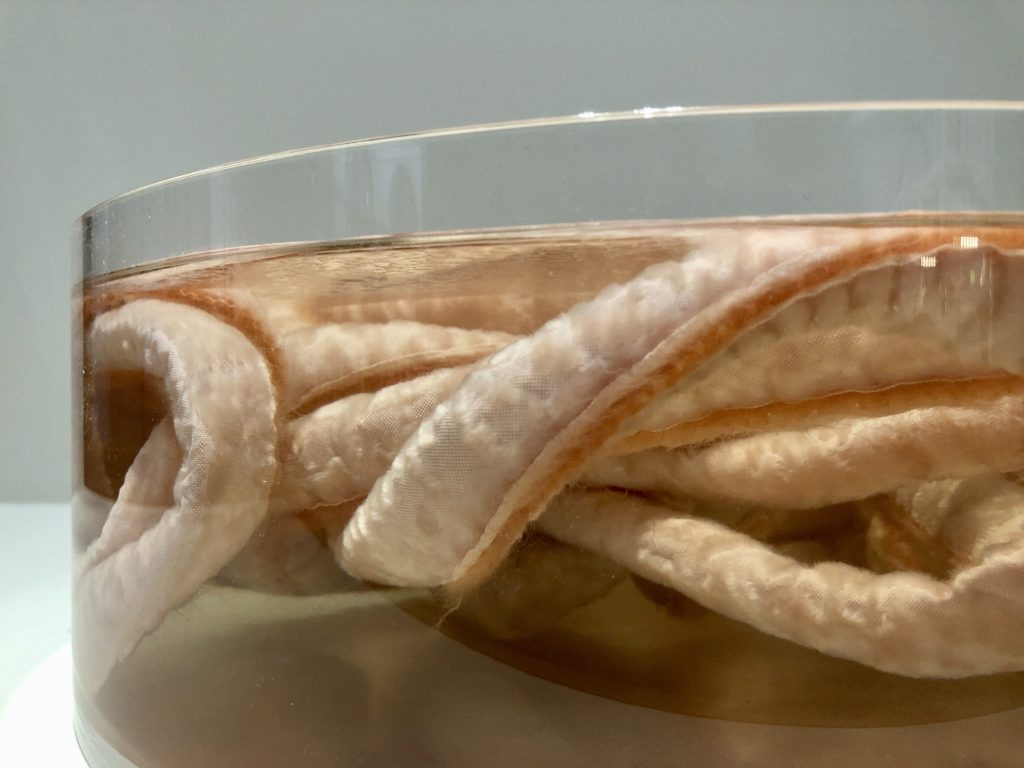

When I meet Dekyndt’s sculptural objects, scattered across the twenty-four vitrines in the Bourse’s circular ground floor space, I find them utterly captivating. At first glance, they look like quintessential minimalism, but the artist’s obsession with organic materials and textures, geographies and processes, destabilise a reading centred on pure form. In one vitrine, two small canvases have been covered in silk velvet soaked in coffee by capillary action. In front of this hypnotising diptych, a roll of early-20th-century paper used for wrapping ammunition sits next to rolls of rooster feathers used for Carnival decorations in São Paulo and yet another rolled object, this one made of translucent natural rubber produced from a tree native to the Amazon rainforest. In a large glass jar next to them floats a lemon covered with a piece of cloth soaked in a gel extruded from quartz. The lemon looks like a small animal that’s both dead and alive. What should be a random assemblage of orange, taupe and cream-coloured objects feels like a compressed history of extractive global capitalism in a single glass case.

Many of Dekyndt’s materials and certain of her references speak to me of Blackness and colonialism. The only video piece on display here, and supposedly her most well-known work (it apparently went viral on social media in connection with the Mahsa Amini protests in Iran), is a film featuring a flag made of long strands of Black hair, planted on top of Diamond Rock on Martinique. Diamond Rock is an important site on the Caribbean island—it’s where a slave ship ran aground in April 1830, killing more than forty slaves, and also home to a tomb of Édouard Glissant, one of the country’s most beloved sons.

Partly because of this particular film, entitled Ombre indigène, and partly because of other materials which appear in her work, I initially assumed that Dekyndt was a Black woman. After walking once around all twenty vitrines, I sat on a bench in the foyer and googled the artist. She isn’t Black as I’d assumed, but a white Belgian artist. Although I remain affected by her work, I start to feel uncomfortable. I start to question the ethics of the connections Dekyndt seems to be making between materials and semiotics, between supply chains and histories of global capitalism—particularly its early origins in empires and merchant trading companies. Among the vitrine still lifes are: bleached hair of ‘Indian provenance’; copper from mines in Katanga, Democratic Republic of the Congo; natural latex from the Amazon’s Hevea brasiliensis tree; a piece of striped bayadere silk from the Indian subcontinent, a type of fabric which spread around the globe because of British colonisation, soaked in Ethiopian coffee.

Were Dekyndt a Black artist, I would—rightly or wrongly—be less wary of her ethics. I’d also be less suspicious of the potential shallowness of her connections to Black intellectual and cultural heroes and the trauma experienced by black bodies. As a white artist, particularly as a white Belgian artist, her explicit lack of a political articulation for the work makes me start to feel that the series is more of an aesthetic fetishisation of coloniality through materials rather than a criticism of it. This latter concern is particularly acute given the 19th-century natural-history museum feel of the tall wooden vitrines in which her objects have been placed. Since visiting this exhibition, I’ve been reading catalogues of some of Dekyndt’s previous shows and the colonial or political aspects seem largely absent. Instead, there’s much more focus on her almost alchemical experimentation with materials and processes, for example transforming wooden cloth with coatings of black cheese wax or creating sculptural paintings with cloth-covered bread dough that has been fermented with wild yeast.

And yet, I’m still drawn to her objects. They excite me. I normally find minimalism draining, depleting, but her approach feels giving and generous, even generative. I can’t stop thinking about the objects and the transformative processes they’ve undergone—the strangeness of certain decisions, the joyful rightness of others. I can’t stop thinking about all of the different geographical connections between these materials, the enormity of the impacts colonial histories have had not only on people and places, but on material and cultural histories, too. As I walk around and around again, I remain as compelled by the affective experience of the work as I do concerned about its ethical limitations. Walking from case to case, I feel like a spider spinning a web between the objects, but a web the scale of the entire world.

Edith Dekyndt is at Bourse de Commerce, Paris until 31 December, 2023

Image credits (from top)

1. Installation view of Edith Dekyndt at Bourse de Commerce, Paris (2022), photo Bourse de Commerce

2. Screenshot of Ombre indigène, Edith Dekyndt (2014), Galerie Karin Guenther

3. Detail view of vitrine 7: traditional Chinese lacquer on Flemish linen canvas, sewn piece of pleated cotton twill brushed with Meudon chalk, Edith Dekyndt (2022), photo Crystal Bennes

4. Detail view of vitrine 24: embroidery checkered table cloth created in Itanhaém, Brazil, stretched on a frame with horizontal threads unwoven and taken out; removed threads rinsed and washed together into a ball, Edith Dekyndt (2022), photo Crystal Bennes

5. Detail view of vitrine 13: velvet edging sewn off of a wooden bedcover, ozonated water, Altuglas wash basin, Edith Dekyndt (2022), photo Crystal Bennes

6. Installation view of Edith Dekyndt at Bourse de Commerce, Paris (2022), photo Crystal Bennes