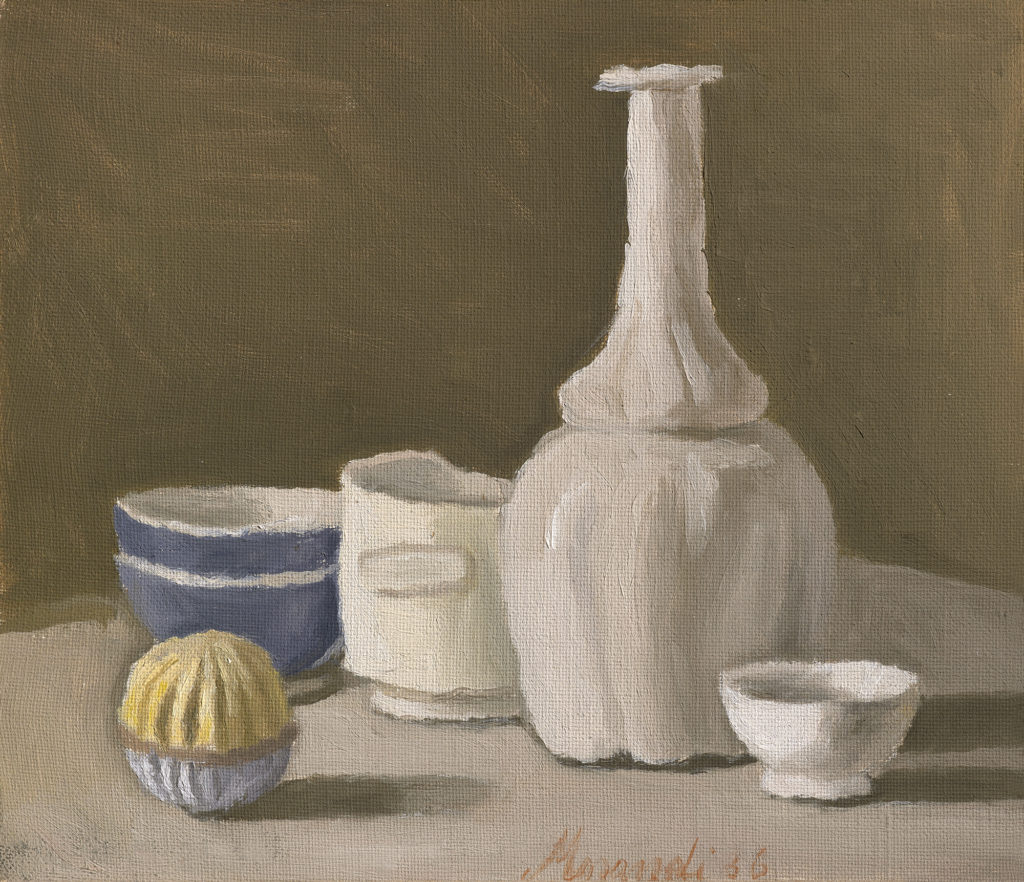

A year ago I started art classes, and in the most recent term, I spent four hours or so trying to recreate a Morandi still life by transcribing it from a print-out. Learning from other artists is as old as art itself, and copying from Morandi taught me that, with my extremely limited skillset, I prefer painting small boring things to large interesting ones. The opening of this new exhibition at Estorick Collection also provided an opportunity to test how starting to paint for the first time in 20 years might change the way I look at – and write about – painting.

The exhibition is divided into three sections: the two ground-floor galleries contain works from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, while an upstairs gallery showcases Morandi works, mostly drawings and etchings, from the Estorick’s own collection. With the ground-floor galleries rather busy when I arrived, I started upstairs and was struck by two main things. The first was the preponderance of landscapes. These owe a clear debt to Cezanne, especially in the patches of hatching to break up flat surfaces and evoke form and depth. What Morandi does though is treat each landscape like a still life (or is it the other way around?), with houses appearing like cartons and chimneys like bottles.

The second was the variety of line. Some of the landscapes are little more than a few rapid pencil strokes. Some are made of big strong lines; others are much more careful, tentative even, where the lines appear in places almost frail.

This variety of line-making is a striking aspect of Morandi’s paintings too. In such minimal works, tiny additions make a big difference, like the smidge of a table edge or a splodge of grey on an otherwise terracotta-toned container. Parts of these little paintings are very precise, with clear, hard lines to demarcate one form from another. In other places, sometimes just the other side of the same object, outlines blur into each other, overlap. Forms feel unstable, objects hard to read. Backgrounds are largely one colour with texture coming from the movement of the brush (this is something I could not glean from the art class print-out where I had mistaken variety of texture for variety of tone). Background greys overlap the greys of the objects or leave gaps. Each thing sits upon a single dark shadow, like an underlining.

This is an exhibition that encourages looking more than thinking. Morandi’s relationship with fascism is not really explored. This is hardly surprising, given the Estorick Collection’s predilection towards Italian futurism, but it leaves a gaping hole. How much can we insist upon the idea of the work as a hermetic escape into the realm of the apolitical, and how much must we recognise the extent to which Morandi espoused – and benefited from – the fascist regime? Nativist and nationalist: Morandi is a great painter but a small-minded artist.

Before art classes I would have written more about Morandi’s apparent lack of politics (which in itself is usually an acceptance of the status quo) or used Morandi to critique the political limitations of object-oriented ontology (all those things touching not touching). Now, I’m equally interested in trying to trace what his paint brush was up to.

Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation is at Estorick Collection, London until 28th May 2023.

Image credits (from top)

1. Giorgio Morandi, Natura Morta (Still Life), 1953, oil on canvas 35.5 x 45.5 cm

2. Giorgio Morandi, Natura Morta (Still Life), 1936, oil on canvas 32 x 37 cm

3. Giorgio Morandi, Natura morta con sei oggetti (Still Life with Six Objects), 1930, etching on copper plate 20 x 24 cm

4. Giorgio Morandi, Natura Morta (Still Life), 1960, watercolour on paper 16 x 20.5 cm