This series of four conversations was originally published on Roman Road Journal, 2018

For scientists, the role of research is long-established: the scientific method, after all, is built on the belief that hypotheses can be tested and so proved or disproved through a process of experimental research. As an institutional discipline, science therefore has a very clear sense of where research fits into the overall process and how findings ought to be presented: in peer-reviewed journals, with statistics, diagrams and written in a scrupulously neutral prose style.

For artists, however, the role that research plays can be much more open-ended – freer but also more complicated. This is especially true of artists who engage with science, for whom research is not merely what is referred to as “artistic research” (often simply material experimentation or learning from the works of other artists), but also research in a more academic or scientific sense: in archives, libraries or laboratories. So how is research for such artists the same as, or different from, research in other disciplines? And when it comes to exhibitions, should the finished work of art exist independently from the research that informed it, or might the two benefit from being presented together? What if the research is the art?

CRYSTAL BENNES: As a one-time academic (my first PhD is in Classics) I have always been passionate about research. In conventional academia, research becomes a finished piece of writing through a well-practised process of selection, citation and synthesis.

As an artist, I’m still fascinated by research, but the relationship between that research and the making of the art work feels much more complicated. It is something I’m still trying to navigate in my own practice. Different artists adopt different approaches but these can be generalised into two main strategies. On the one hand is somebody like Trevor Paglen, whose work enacts a making visible of the technologies of surveillance, data, and communication employed by the US government. In the gallery, his work usually exists as singular art pieces or series of photographs. His position is that the image signals towards the research, and if a viewer is interested, they can go and look up the subject as they wish. It’s almost an idea of the artwork as a gateway.

TOM JEFFREYS: Like a catalyst for conversation.

CB: Or a portkey…

TJ: Needless to say, Paglen does a lot of interviews.

CB: Yes, there was a good one late last year in MONO.KULTUR, where he outlines the tension between material objects and abstraction. He says that when he was in art school, the idea that good art had to be self-contained was omnipresent, but that he’s more interested in building an external armature outside the images. ‘I’ve always felt that nothing can contain itself, that things are constantly being defined outside of a frame and are inevitably part of a larger system,’ he says. ‘What would happen if you build out that aspect as part of a ‘meta-art’ project? It would mean writing books, and creating a whole constellation from other media to try to give people pathways into the art.’

On the other hand, you have artists who try to reconcile that binary and incorporate the ‘armature’ into the work itself. Something like that super film we both saw in Finland a few years ago.

TJ: Yes, Lauri Horelli’s Jokinen at Muu galleria in 2016 – a 45-minute film that told the story of a Finnish immigrant living in New York in the 1930s, his involvement with the communist party, civil rights activism, and subsequent deportation to the Karelia in eastern Finland.

CB: What I loved about that piece was the way it spoke both to this particular historical episode, but also to the research processes which underpin the telling of history.

TJ: Yes, although the film doesn’t really relate to science, it told its story through a bringing-together of newspaper clippings, archival documents and photographs as well as the paraphernalia of research: highlighter pens, post-it notes and box files. You watch as the hands of the artist-researcher cut out photographs, highlight sections of text, and pieces together the story by making collages of the research material.

CB: The question that Horelli is tackling, by contrast to Paglen, is how do you make the research the work, rather than the work being a signifier for the research. For me, that’s a much more interesting approach, but also more difficult and frustrating.

TJ: The Paglen approach is probably the standard one in contemporary art, especially towards the top of the tree, where artists have to focus more on spectacle than ideas or process. Look at Olafur Eliasson or James Turrell or Carsten Höller. Höller, who has a doctorate in entomology, incidentally, is extremely knowledgeable about many aspects of plant and animal biology, but you would struggle to get much of that from the works alone.

CB: Agreed. I find that quite depressing, actually.

TJ: Similar to Paglen in some ways is an artist like James Bridle. Bridle is also interested in technologies of surveillance and the politics of communication infrastructure. A lot of his research is fascinating and he has written many brilliant texts, but I’ve never been convinced that his research translates all that well into art. I remember seeing a piece he’d done in Brighton a few years back (Under the Shadow of the Drone, 2013). Bridle was there at the press view and spoke very engagingly about the research he’d been doing. But I found the work itself – an outline of a Reaper drone on the pavement by the seafront – underwhelming, at best. With this kind of work, to follow Paglen’s line of thinking, why make art at all? Why not just write articles and books and carry out interviews?

CB: But between, say, Horelli on the one hand and Paglen on the other is a broad middle ground.

TJ: For sure. One common strategy is an accompanying text of some kind: Sophy Rickett, for example, whose work has recently looked at things like species loss or astronomical image-making, often produces booklets containing essays or stories to be read alongside her solo shows. In an institutional context, research can often be presented alongside the work more physically, although sometimes this gets relegated to a separate space at the end of the exhibition. It’s often a curatorial strategy rather than one conceived by the artist. It can feel a bit clunky or half-baked sometimes, but it can work well.

CB: Like Anaïs Tondeur’s show at GV ART, London back in 2014.

TJ: Exactly. Anaïs is an artist we both admire. Her work is materially and conceptually complex and she is extremely knowledgeable. For that exhibition, which included sculpture, slow-motion video, drawing and photography, there was also, in a small separate room, a mock-up of the artist’s studio, complete with shelves of books, sketchpads, pencils, photographs etc. It was a simple, but effective way to showcase the breadth and detail of the research that had gone into the exhibition.

Nonetheless, each of these approaches is a supplementary strategy. They may be very effective but they still maintain the distinction between art on the one hand and research on the other. Although this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

CB: For me, there is one artist group that has been especially successful in pulling apart or even collapsing this distinction: Forensic Architecture. They see research as art and vice versa, the research is the work and presented as such. And I would say that their work is science as well. They’re interested in the history of forensics and the trajectory of all those methodologies. In their recent exhibition at the ICA in London, for example, the wall text in the main space outlined the development of forensics as a science, how it emerged within a juridical and criminal context—and is still tinged by that history.

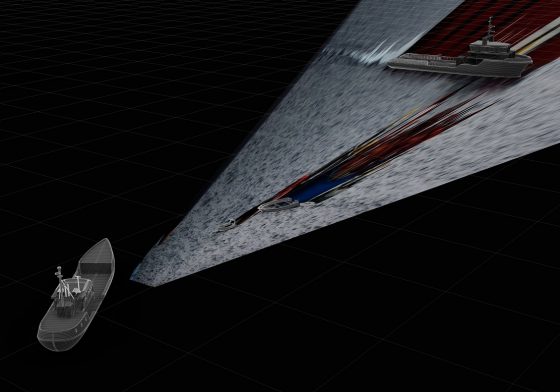

Likewise, with Forensic Oceanography whose devastating Mare Claustrum installation we both saw recently at Manifesta 12 in Palermo. Their research reconstructs events in the context of the militarised border regime in the Mediterranean Sea to make visible the horrible violence perpetrated against migrants attempting to cross to Europe.

I wouldn’t even say that what Forensic Architecture or Forensic Oceanography do is a marriage of research and work, which implies that they could be separated in some way. The two are so deeply connected – very few artist and artworks I can think of that are like that.

TJ: In your own work, how would you distinguish your research as an artist from the research of a scientist or even from your earlier research as an academic?

CB: That’s one of the most interesting questions, I think. It’s not always easy to answer. I have a tendency to turn first to libraries and archives, because those are places where I am very comfortable. There’s also research directly in the field, so to speak – going to scientific conferences, making laboratory visits, etc. There’s this cliché that artists turn up and ask stupid, irrelevant questions – but as someone who hasn’t been brought up in a particular discipline and schooled in all of its assumptions, it’s often that these questions are outside the intellectual or emotional norms of the discipline and may seem a bit left-field.

The hardest part is then finding a way to turn research into a thing, an object, which art still seems often to demand. As an artist, you’re judged on production. You get exhibitions, grants, media coverage based on what you make, not what you research. This is something I still struggle with.

When I’m experimenting materially with something, be it photograms in the darkroom or etchings in the printmaking studio, somehow, I never think of that as research. It’s when I’m in a lab or an archive or interviewing scientists, gathering interesting material, that’s what I think of as research.

It’s the effort to bring these two together which often fills me with frustration, like there’s an explicit process of translation required to move from research to making, a process which still doesn’t feel very intuitive or even necessary.

One recent example is ≠ C8H803, an installation about vanillin that I was commissioned to make for Science Gallery Dublin. In some ways, it was a good installation. But from the research process, I knew so much interesting stuff and I really wanted to talk more about vanilla, which is such a fascinating, complex, difficult subject that touches on a lot of bigger questions. I found that there was something depressing and disappointing about not being able to adequately translate that into a material language

As the artist, you have all of this knowledge but you’re not always able to bring that to the audience. Maybe the problem is in the materialising; maybe immaterial approaches are better able to capture that complexity – either in talks or in film or video, which are material and immaterial at the same time.

TJ: You’ve been giving a number of lectures recently, which you seem to have found more satisfying in some ways, especially in terms of this specific question around the presentation of research. It reminds me of that performance-lecture I saw by Haig Aivazian at Kadist, Paris in 2017, which is a great example of what we’re discussing.

Aivazian had done amazing research into the technologies of the state of exception in France, in surveillance tools developed by the Israeli military and how these were used to track players in football matches and monitor crowds at the Stade de France. The work touched on the history of public lighting in France, violence in Gaza, racial segregation in the Paris suburbs, predictive policing algorithms and many other things besides.

In the exhibition itself, I felt that the material objects struggled to convey the multiplicity of meanings that had accreted upon them. But a film piece, and in particular, a performance-lecture, entitled World/Anti World: On Seeing Double, were much more effective in weaving together the multiple threads that Aivazian’s work touches upon.

This kind of event, which is at once material and immaterial, which employs both language and aesthetics, which foregrounds to some extent the bodily presence of the performer, and is somewhere between a lecture and a performance, could be quite a productive avenue for you too I think.

CB: I honestly thought that was such a brilliant, complex, layered piece of work. It’s definitely an appealing space to explore.

Images

1. Anaïs Tondeur, Nuuk Island, Lost in Fathoms (2014), shadow gram, courtesy the artist and GV Art

2. Installation view of ‘Counter Investigations’, Forensic Architecture, Institute of Contemporary Art, 2018, photo Mark Blower

3. Film still of ‘Mare Clausum,’, Forensic Oceanography, Manifesta 12, 2019

Further Reading

Haig Aivazian, 1440 Sunsets per 24 Hours (interview), 2018

James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (Verso, 2018)

Trevor Paglen: The Edge of Tomorrow MONO.KULTUR #44 Autumn 2017

Sara Morawetz, In Observation: The Definition of an Experimental Method, 2014