I’m standing in the square outside Basel’s Münster cathedral. An old man dips two wooden poles into a large bucket of water. Drawing them out and apart, perfect vanitas bubbles bloom and drift upward toward the spires. Delighted children compete to pop them as a pair of falcons scout for lunch overhead, their sharp cries mingling with the dreamy concerto leaking from the bubble man’s radio. I’m in a good mood, mesmerised, even moved. Sometimes you feel acutely open to the world; sometimes you shut it out. That difference, I think, shapes how you encounter art. In two days in Basel I see more good work than I have in a long time. I can’t tell whether that’s because of the art or my own emotional rawness. Probably a bit of both.

Emilia Bergmark at Von Bartha

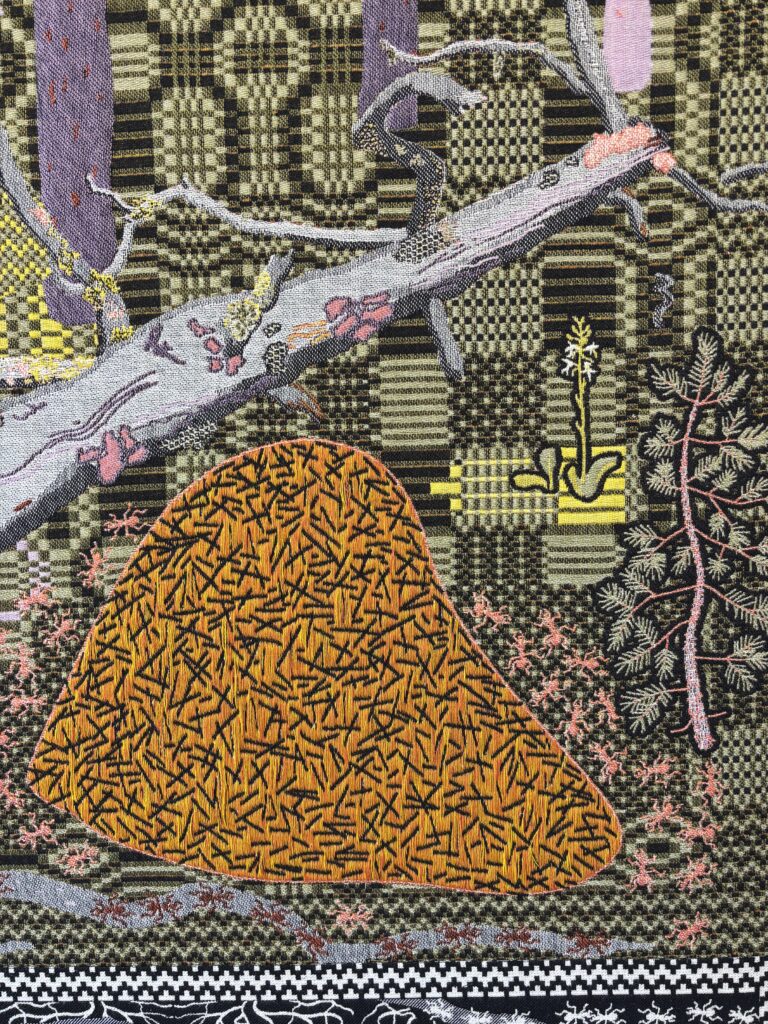

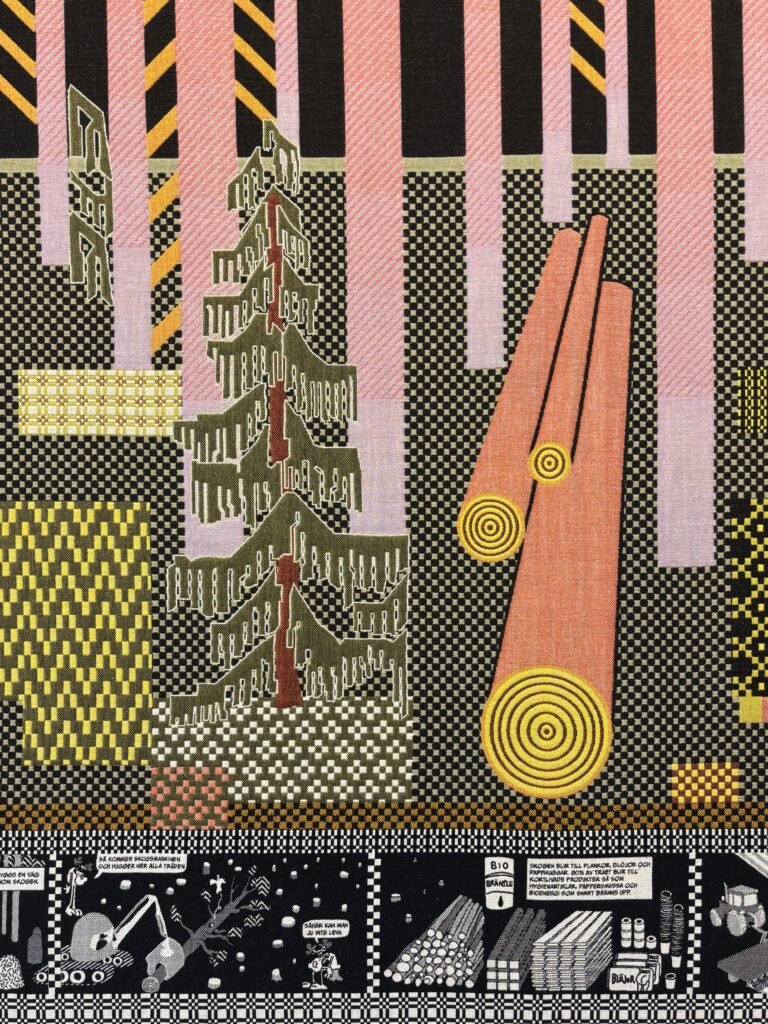

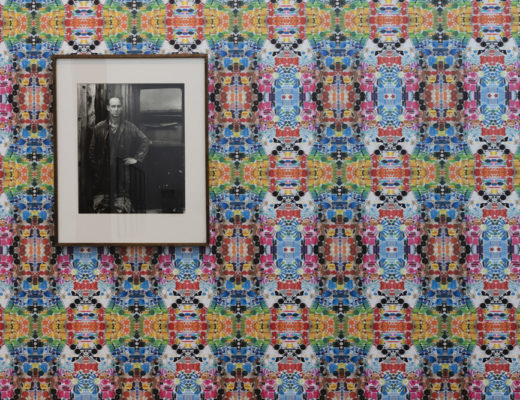

At Von Bartha, Florian Slotawa’s appropriated trays, jerry cans, steel bars and slatted frames—abstracted sculptural riffs on Kandinsky’s point and line to plane—give very little. Work sealed inside a bubble of art-world references has never much appealed. Emilia Bergmark’s Jacquard tapestries, addressing the environmental destruction wrought by Sweden’s forestry industry, are far more compelling. Her textiles draw from graphic novels, early computer graphics, mille-fleurs tapestries and 1960s design patterns. In muted purples, greens, pinks and blues, one tapestry depicts the dense biodiversity of an ancient boreal forest in Dalarna. The second, rendered in highlighter pinks, oranges and olive greens, shows the emptied uniformity of an industrial plantation forest. Both are edged top and bottom with black-and-white comic-strip borders, where a white moose laments habitat loss as Sweden shifts from forest-rich playground to endless monoculture. In Bergmark’s hands, the decorative domesticity of traditional textiles are reworked, sharpened to a point to expose the violence concealed within Sweden’s green national myth.

Walter Pichler at Contemporary Fine Arts

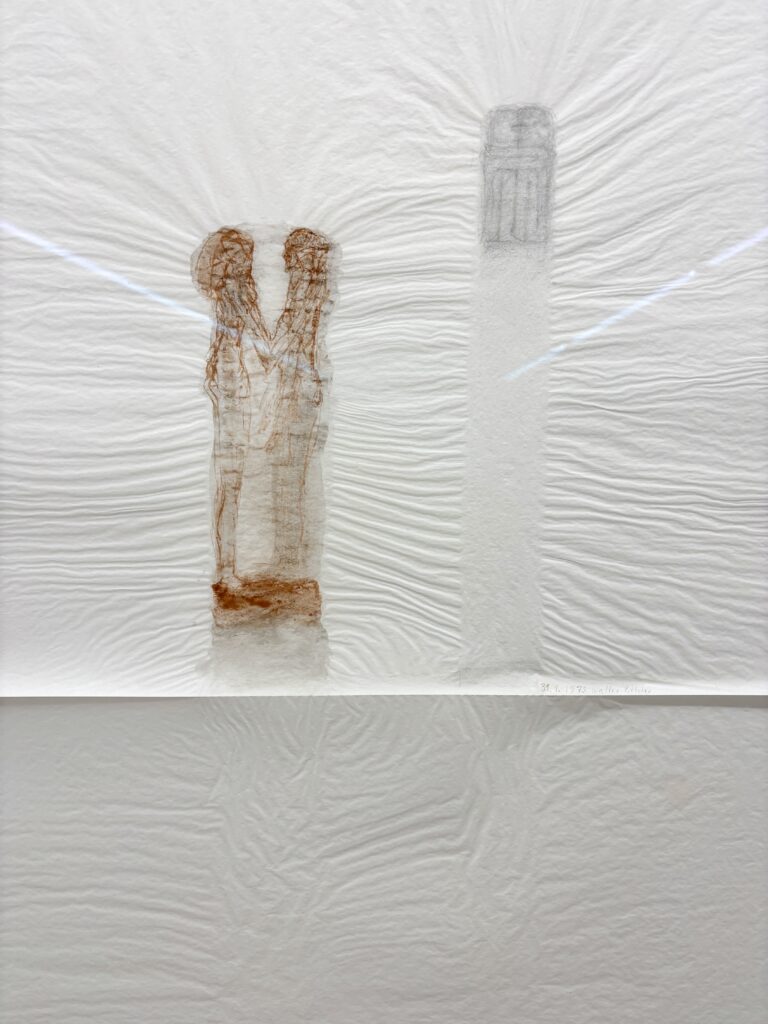

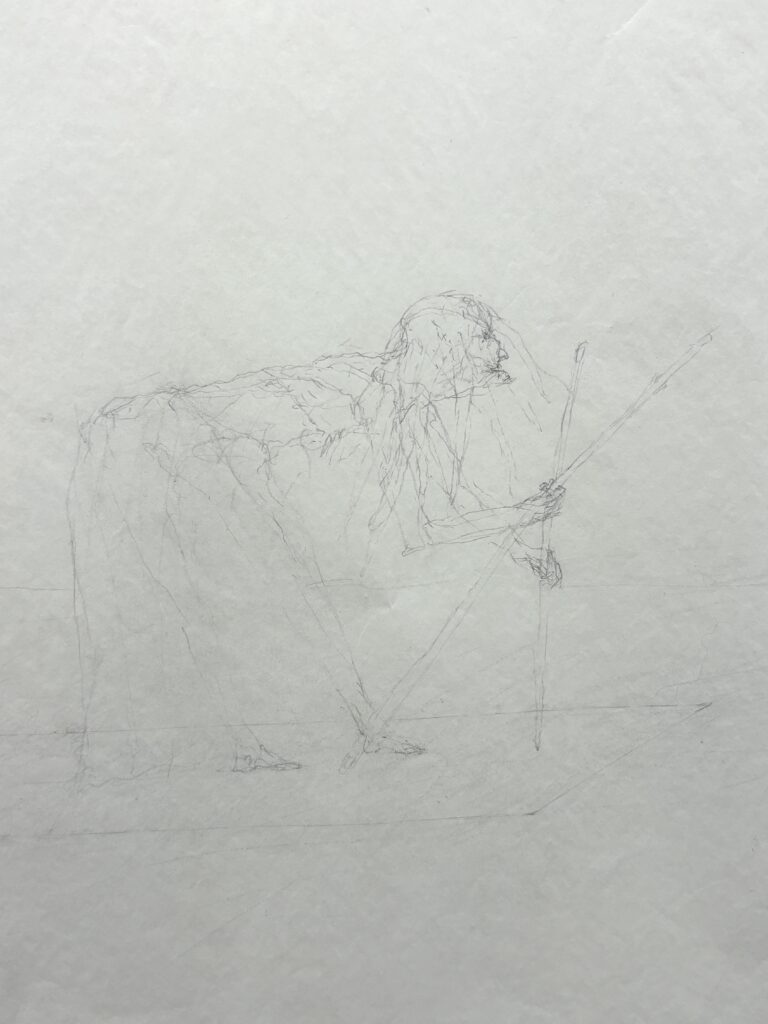

On my way to Kunsthalle Basel, I stop in at Contemporary Fine Arts to see a Walter Pichler show curated by Cyprian Gaillard. Pichler isn’t a favourite, yet I find myself hypnotised by several drawings. In an ink the colour of iron-rich earth, two barely articulated figures face one another, hands clasped. The paper is fine—washi perhaps—and somehow, through embossing or pressure or rivulets of water, deep lines radiate from the bodies like visible magnetic fields. Another drawing shows a bent figure, maybe an old woman, gripping two canes. I’m sure I’ve seen her before, though I can’t place where. There’s a faint echo of John Flaxman, but Flaxman is too crisp, too resolved. These are loose, hurried, almost messy. So few lines, yet the imagination does the rest: a lesson in how to say a great deal with very little.

Eva Lootz at Kunsthaus Baselland

Eva Lootz’s exhibition was meant to close at the end of January, so its extension felt like a gift. Born in Vienna and based in Spain since 1967, Lootz operates somewhere between Arte Povera and minimalism. I don’t normally relate to minimal sculpture, but Lootz’s work is underpinned by a concern for feminist ecology and political struggle which gives me more to engage with. Her work tackles heavy political issues—extractivism, inequality under capitalism—using a formal material language that is surprisingly quiet and light.

In Salerio (2004), some forty wooden blocks form a spaced herringbone pattern on the floor, each topped with a small mound of salt flaring outward like a cloak. Paraffin-dipped willow branches hang upside down from the ceiling, their waxy skins glinting like crystals in the raking light. Photographs of mines and saltworks pepper the walls. Salt and salary converge through salarium, the Latin term for salt, once tied to payments and allowances. The unspoken question: who will pay for all this environmental damage?

Black Tears (1997)—nine oversized black wool teardrops suspended from the ceiling—is an elegy, but also perhaps a declaration of resistance and renewal. Nearby, a wall text in cut-out mirror reads: “seek and learn to recognize, who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space”.

The Manilla Room (1993) gathers dresses, shoes and jewellery sculpted from crumpled manilla paper on a low square plinth. Lootz has spoken of her need to learn to make something from almost nothing after moving to Spain, which eventually led her to this humble material. More recently, on discovering its colonial origins, she added two sculptures shaped to resemble rope, in acknowledgement of the paper’s manufacture from the “waste” of Spanish colonial rope-making industries reliant on the Philippine abacá plant.

The exhibition is beautifully attuned to the Kunsthaus’s architecture. Lootz’s works hold their own against high ceilings, concrete walls and hard geometry. It feels important that this work is being presented now. Lootz is part of a long under-documented generation of women artists finally beginning to receive recognition. Lootz is preoccupied with materials that shift state: salt, paraffin, water. Perhaps her work gestures toward us, too. Faced with such environmental devastation, one hopes people remain malleable enough to change how we treat the earth, and each other.

Carl Cheng at Museum Tinguely

I had been especially looking forward to Carl Cheng’s retrospective. Originally trained as an industrial designer, Cheng’s work borrows freely from industry and science: vacuum-moulded plastics in Nowhere Road (1967), a photographic collage of an atomic blast over an empty highway; elaborate machines simulating erosion on his “human rocks,” plaster forms embedded with technological debris (Erosion Machine No. 4, 1969–2020).

The critical force of certain works are lost in translation to the gallery. First Generation Family Entertainment Center (1968), a glass tank of brightly coloured water mechanically churned into abstract wave patterns, was originally installed within a mock living room. Cheng argued that television functioned less as content than as visual stimulation—flashing light and colour over meaning—so why not present those elements alone? In the white cube void, Cheng’s critique of mass media as an imperialist tool for nuclear family normatively is considerably softened.

In 1967, on graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles, Cheng formed an LLC, John Doe Company. Cheng’s use of the corporate structure is both witty and pragmatic. Adopting the generic white name John Doe—also the police label for unidentified corpses—he turned the company itself into a gesamtkunstwerk, where art, branding and false identity were inseparable. Works made under the guise of John Doe ranged from the technologically sophisticated to the decidedly analogue. Early Warning System (1967 – 2024), a ziggurat of blue plastic cubes, is a live radio stream of maritime weather forecast alongside projected images of oil spills and garbage dumps. Inside a greenhouse, the results of hundreds of experiments with avocado seeds and skins—every one eaten by Cheng—sit on resin-filled trays in Organic Laboratory (1998–2024). There’s something faintly absurd in incorporating a business to present hundreds of small sculptures of avocados as a kind of detailed lab experiment, yet that absurdity is part of the point.

The exhibition closes with a survey of Cheng’s public works, including Sand Rake (1978–2–22), a vast concrete roller that embossed an aerial map of Los Angeles into Santa Monica beach, its ephemerality a decided counter to the monumentality expected of public art. Change, erosion, impermanence—these are Cheng’s constants. His work is playful, ingenious, often dazzling, yet it rarely lands an emotional punch. Nature may never lose, as the exhibition title declares, but what does that mean for those of us living in the meantime?

Daniela Ortiz at Kunsthalle Bern

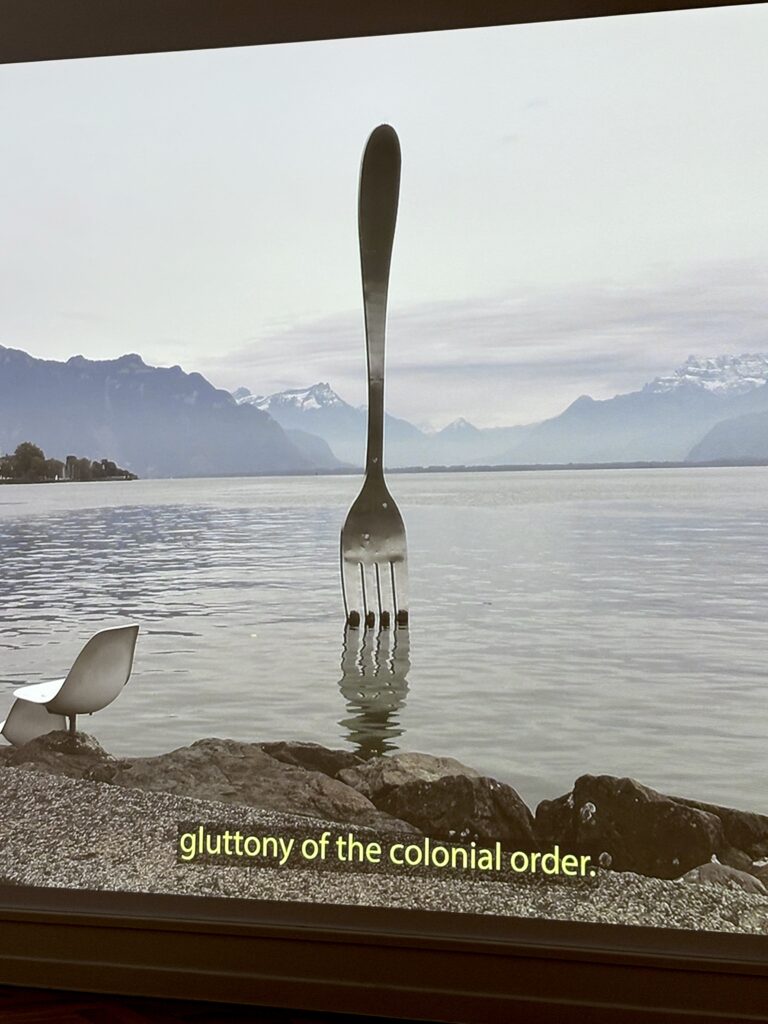

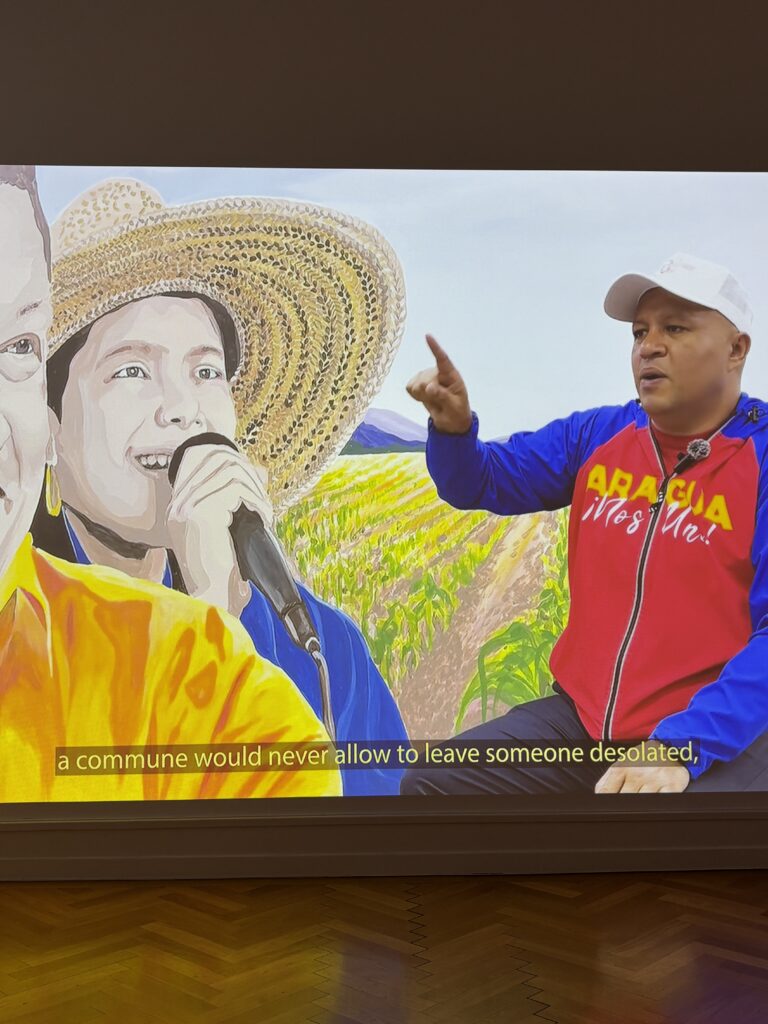

An hour by train brings me to Bern for the final day of Daniela Ortiz’s A Drop of Milk. Ortiz is well known for her uncompromising political practice, highlighting the violence of imperialism and capitalism across the Global South, particularly in Latin America. This exhibition examines hunger as a form of collective punishment on the Global South imposed by the political and economic structures of the Global North, with a pointed focus on Switzerland.

At the exhibition’s heart is a thirty-minute film in which Nestlé comes sharply into view. In an extended shot, an enormous sculpture of a fork—plunged into Lake Léman near the company museum—becomes a grotesque emblem of corporate overreach. Nestlé’s claim to feed the world collapses against the artist’s evidence of hoarded milk formula in Venezuela and Chile, a practice used to destabilise leftist movements. Ortiz further traces a line from Swiss corporate power to state action: the 2018 sanctions on Venezuela and 2026 asset freeze.

The film resists Swiss corporate narratives by foregrounding communal food systems, particularly in Venezuela, that push back against U.S. sanctions and profit-driven carceral capitalism. Nearby, eighteen painted tin plaques echo these stories. Drawing on the floral borders and pastoral scenes of bauernmalerei, Ortiz appropriates folk aesthetics to expose how Swiss trade and food policy undermine food sovereignty elsewhere, particularly in Cuba, Venezuela and Palestine (Bauernmalereien, 2025). In the back room, across from the screened film, a vast golden banner reads “COMUNA O NADA” in red block letters. Rather than offering critique alone, A Drop of Milk insists that only organised communal infrastructures—rooted in land, food, and mutual obligation—can withstand and outlast imperial capitalism.

Image credits from top. All images TPR unless otherwise stated:

1. Installation view, Emilia Bergmark, Boreal Natural Forest and Boreal Tree Plantation (2025), Image: Von Bartha, Finn Curry.

2. Detail Emilia Bergmark, Boreal Natural Forest (2025)

3. Detail Emilia Bergmark, Boreal Tree Plantation (2025)

4. Detail Walter Pichler, “31.1.1973” (1973)

5. Detail Walter Pichler, title unknown

6. Eva Lootz, Salario (2004)

7. Detail Eva Lootz, Salario (2004)

8. Detail, Eva Lootz, Sin título (Gestos encontrados, 1) (1976 / 2025)

9. Eva Lootz, Lágrimas negras (1997)

10. Detail, Carl Cheng, Organic Laboratory (1998–2024)

11. Carl Cheng, Nowhere Road (1967). Image: Museum Tinguely, Robert Wedemeyer

12. Carl Cheng, Erosion Machine No. 4 (1969-2020). Image: Museum Tinguely, Jeff McLane

13. Daniela Ortiz, Comuna o Nada (2025)

14. Daniela Ortiz, still from A Drop of Milk (2025)

15. Daniela Ortiz, still from A Drop of Milk (2025)

16. Detail, Daniela Ortiz, Bauernmalereien (2025)

No Comments