February 2025: this conversation actually took place back in September 2024 in the immediate aftermath of some strategically incendiary funding announcements from Creative Scotland. But then we both had other things to do and now suddenly it’s February. Well, better late than never, right.

In the interim, the big news from Creative Scotland was the January announcement of multi-year funding for lots of organisations. The main good thing to have come out of this is that these chosen organisations can now actually plan more than a few months in advance, and hopefully devote some energy to programming great work rather than just chasing after tiny pots of funding.

For people only paying a bit of attention, you could be forgiven for thinking that Creative Scotland had got its act together, what with every funded arts organisation in Scotland going out of its way to express its deep and very public gratitutde to Creative Scotland for somehow managing to do its job with something approaching competence. What was concealed among all that was, well, a lot: firstly, the arts organisations that were not successful in their applications (despite also having to spend so much time filling in all those labyrinthine forms); secondly, that many arts orgs singing their gratitude in public were left to privately solve the fact that Creative Scotland in many cases only awarded them a fraction of the funding they actually need; thirdly, the ongoing dominance of Scotland’s funding landscape by a few big (and often quite shit) organisations, £12 million for Edinburgh International Festival being only the most egregious example; oh, and fourthly, the fact that that the situation for artists and other creative practitioners is still, as they say, fucked.

September 2024: £100 million for the Commonwealth Games but almost nothing for artists. It’s time to talk about the woeful state of arts funding in Scotland.

CRYSTAL: We wanted to have a wider conversation around arts funding in Scotland at the moment, partly in relation to the Baillie Gifford campaigning, which we’ve both been actively involved in, but also in relation to the more recent debacle over funding at Creative Scotland. Where should we start?

TOM: I mean, how long have we got! What about the protest outside Holyrood on 5th September? You mentioned at the time how weird it felt being there.

CRYSTAL: A lot of that was to do with how angry I was at Creative Scotland, as well as the entire Scottish arts sector more broadly. Creative Scotland intentionally stoked confusion and panic among artists in order to use that anger as leverage against the Scottish government. They knew exactly what they were doing, and I think some others did as well, but many, many people didn’t read what was happening as a deliberate tactic, and panicked. Creative Scotland’s actions were extremely irresponsible. I was also incredibly angry about the way certain parts of a sector, which has been deafening in its silence about the ongoing genocide in Palestine, suddenly found its collective voice when its funding was pulled.

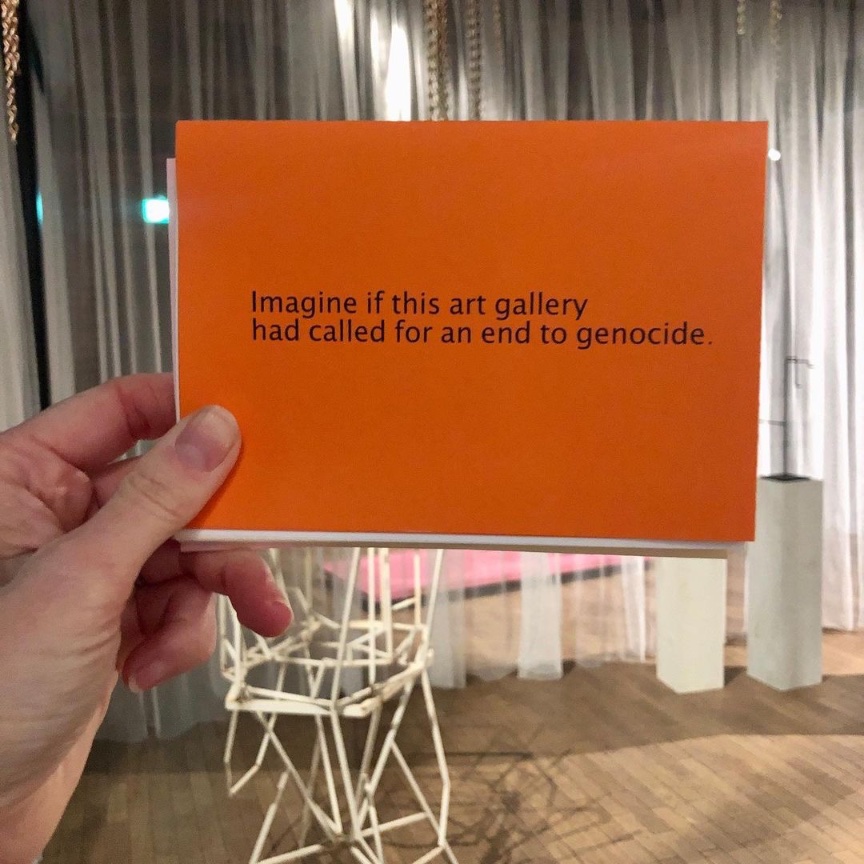

TOM: I think for me, a related source of anger/confusion came from seeing senior Creative Scotland managers attending the protest and cheering along, when – as you say – they really should be taking a significant portion of blame for the entire situation. Similarly, seeing directors of Scottish cultural organisations clapping along to chants of ‘Free Palestine’ when those same directors have been partnering up with Zionist funders, been silent on genocide and indeed actively complicit – it’s hard not to feel really quite angry. The event made visible a lot of the art world hypocrisies that have been bubbling away for years, but particularly over the last ten months.

CRYSTAL: It certainly wasn’t an event where I felt like cheering, that’s for sure. The fact that this exact same pattern has been repeated multiple times in recent years demonstrates that sector-wide organising seems to be a tactic of last resort, only when government budgets are withheld, rather than standard operating procedure. But yeah, the discrepancy between how people behave in situations where institutional budgets are endangered versus when human beings are endangered is galling.

TOM: Yeah, that was made very clear to me when I emailed all the directors of major cultural institutions who I had some vague connection with. On the funding stuff, most of them wrote back straight away to list all the work they were doing behind the scenes. And it was such a marked contrast to the deafening silence I received from emailing people about Palestine solidarity statements or taking funding from Baillie Gifford. On the one hand, it’s impressive and heartening to see people come together to get shit done. But on the other hand, if they can do it for this, why can’t they do it around complicity in genocide?

CRYSTAL: Right. By contrast, having worked so long around scientists, they are very good at consistent, high-level lobbying. They have cross-institutional committees and take this work very seriously as they know it means the difference between sustained funding or not for their work. I don’t see the arts industries lobbying like that here. Maybe part of the problem is that, over the last twenty plus years, maybe longer, capital development funding has completely dominated the funding landscape. Institutional directors have acquiesced to right-wing policy ideas around funding for the arts whereby assets that accumulate interest, such as new extensions or new buildings, are a good use of government funds, whereas artists, who don’t generate any appreciable interest, are a bad use of government funds. The directors of too many of Scotland’s cultural institutions, many of whom have been in the same job for decades, haven’t fought hard enough against the swing away from funding for the arts and for artists towards capital development projects.

TOM: It’s the same pattern with universities, right? Huge swanky new buildings, but ever-more precarious working conditions for staff.

CRYSTAL: True.

TOM: I remember when we were living in Helsinki, there was a push to build a Guggenheim museum there which none of the artists really wanted (the extractive nature of the Guggenheim funding model is a whole different conversation!). The big tourist-focused businesses publicly committed to contributing some funding but when the Guggenheim was voted down, they couldn’t really back out and it was then possible for that money to be re-oriented towards initiatives that the local art scene actually wanted – specifically the Helsinki Biennale. I’d love to see cultural managers in this country make that same move: “Oh so there’s money for buildings you say? Well we’ll take that money and spend it on artists. kthanksbye!”

CRYSTAL: I agree. What’s the point of all these buildings and no ecosystem to help support and sustain artists? Rental accommodation is expensive and difficult to obtain, studios are thin on the ground, expensive and also difficult to obtain (I think I’ve been on one waiting list for seven years!), and there are very few opportunities for artists to show work in Scotland. That said, I do also think we need to be careful of seeing Scandi countries as overly-idealised models. There are many good things about how arts systems and structures function in, for example, Finland or Sweden, but there are also many problems and strains with the systems, too. Finland is experiencing significant budget cuts to the arts right now, too, and there is a lot of organising and campaigning going on there to protect funding.

TOM: For sure, but they do offer good models for some things. One thing that Finland does way better than Scotland or England is the comparative lack of bureaucracy when it comes to applying for funding. You might not be any more likely to get the funding but at least you haven’t had to waste a week of your time filling in endless application forms.

CRYSTAL: Lord, that is definitely true. I recently applied for funding from the Norwegian arts council and it was a hundred times less time-consuming than a Creative Scotland application. They just asked for a brief description of the project and a budget, that’s all. Creative Scotland asks you to justify the public benefit of the arts before asking you how receiving this funding will help you become a more sustainable artist so that you don’t need to apply for Creative Scotland funding again. This says everything you need to know about how the Scottish state views culture. But yes, they could do with an overhaul to simplify the application process.

TOM: This always makes me think of something that artist Maria Kapejeva posted on Facebook years ago. Something along the lines of: “I spend less time being the artist Maria Kapajeva than I do being the administrative assistant for an artist called Maria Kapajeva.”

CRYSTAL: Jesus, I feel that. Ok, we’re getting a bit side-tracked.

TOM: Yeah, sorry.

CRYSTAL: Let’s talk about where this all started, which was the mid-August announcement by Creative Scotland saying they were closing the Individual Open Fund. Most people seemed to read the announcement as a permanent closure of the fund, rather than just for the rest of the financial year until April 2025, which is how I understood it. Either way, the completely unnecessary confusion and panic generated by the lack of clarity meant that Creative Scotland received six months worth of funding applications in just 11 days, thereby massively exacerbating the problem of funding shortages.

TOM: The panic and confusion was widespread and very real. That it was stoked strategically by Creative Scotland is pretty gross to see – especially for an organisation that is supposed to nurture artists across Scotland, not leverage their precarity to secure its own budgets. It was also noticeable to see how quickly many organisations came out with political statements about no art without artists after saying for months that they couldn’t make political statements around Palestine. I do understand some of the reasons for this, but the disparity was very glaring.

CRYSTAL: And deeply frustrating.

TOM: What about the timing of the announcement during the August festivals – does this feel like it was strategic?

CRYSTAL: Honestly, I don’t see it that way. The festivals are a smokescreen covering up for the fact that Scotland’s cultural sector has been completely hollowed out. The festivals make it seem as if Scotland has a thriving cultural landscape when what it really has is something on life support.

TOM: It reminds me of that classic Morven Cunningham article from 2020. It’s specifically about Edinburgh but kind of applies to the whole Scottish funding situation: Morven likens the cultural ecology to “an ailing coral reef” – it’s “bright and colourful on the outside, but grey and brittle at its core”.

CRYSTAL: There’s also an overlap with the festivals and festival tourism as a panacea for all economic ills in Edinburgh in particular, which couldn’t be further from the truth. Anyway, it was also interesting to see how much of the widespread criticism was levelled at the Scottish Government and not so much at Creative Scotland, apart from maybe on Instagram stories.

TOM: Certainly from our sphere that’s true. There has been criticism of Creative Scotland, but the most vocal has been coming not from the cultural sector but from the transphobic right, who are basically using this as yet another way of trying to dismantle all funding for anything except the police and military, big business and newspaper tycoons. I guess this comparative absence of criticism of Creative Scotland from the left is also a reflection of this country’s lopsided media landscape. Seeing one white dude write the same bilge for three different right-wing publications feels pretty typical. Like, where is informed, constructive criticism actually going to be published?

It’s also interesting to note that culture minister Angus Robertson has announced a full-scale review of Creative Scotland.

CRYSTAL: Wasn’t he recently heavily criticised for having a secret meeting with Israel’s deputy ambassador to the UK?

TOM: Yup.

CRYSTAL: Apparently the Scottish government is refusing to release the agenda or the minutes of the meeting. Why don’t you release the minutes, Angus?

TOM: Right. But in terms of Creative Scotland, with Robertson having announced a review, you can see why the Spectator/Daily Mail crew are keen to make sure they shout their shitty opinions the loudest to ensure they can influence the framing of any future decision-making and undermine the principles behind arms-length funding bodies. Which is why it is especially important that those making these decisions actually listen to artists. And that those who are supposed to be leadership figures in the sector ensure that those voices are heeded.

CRYSTAL: In terms of the right-wing attacks, Creative Scotland really haven’t helped themselves with how they handled public scrutiny over Rein. Instead of defending the artist, they completely caved and allowed the narrative to be controlled by right-wing media.

TOM: Totally agree. The way Creative Scotland publicly lied about that project, completely exposing precarious freelance artists to the most aggressively toxic elements of the UK media demonstrates a shocking lack of care and consideration for the people they are supposed to support. We’ve seen it time and again: the classic institutional move, take all the credit for artists’ work when it goes well but as soon as there is criticism they pull up the drawbridge, deny everything, and leave the artists outside to take all the flak. Then when they think it’s over, they pop back up again as if nothing has happened. It’s so gross.

CRYSTAL: It’s also been real grist for the mill of far-right voices who think that there shouldn’t be any funding for the arts. What I find so worrying is that Creative Scotland seem to have tacitly adopted a lot of this thinking, and not just recently, but over a longer period of time. Even what I mentioned before about the application process asking you to demonstrate how obtaining funding will help put you in a position to not have to apply for future funding. If that isn’t representative of an underlying ideology where arts funding is only a net benefit to society if it helps artists establish commercially-successful businesses then I don’t know what is.

TOM: I mean, it’s neoliberalism 101. Arguably, the arts have simply failed to justify themselves as useful to a neoliberal agenda, so they become an optional plaything for the rich until they get bored. There was a piece in the FT recently that described HarperCollins (one of the five biggest Anglophone publishers in the world) as merely “one of the less-coveted chess pieces” in the Murdoch family squabbles.

Public bodies should be countering this bullshit not running according to the same logic. The job of Creative Scotland is to distribute money to cultural workers and artists, not to hold on to it as if it’s theirs or to make it absurdly difficult to access. Weirdly, the pandemic provided a good example – the government gave Creative Scotland money to distribute to artists and they distributed it comparatively easily. You filled out a simple form, confirmed ‘I’m an artist and I need the money’, and that was pretty much it. For sure, Creative Scotland can’t necessarily control how much money they get to distribute (although they should be doing a much better job to persuade government that culture needs public money) but they certainly can control how easy or difficult the process is to request that money.

CRYSTAL: I agree that they should simplify and streamline the application process. It imposes an unnecessary burden on people applying for funding. I know you also wanted to talk about the survey that Creative Scotland recently published.

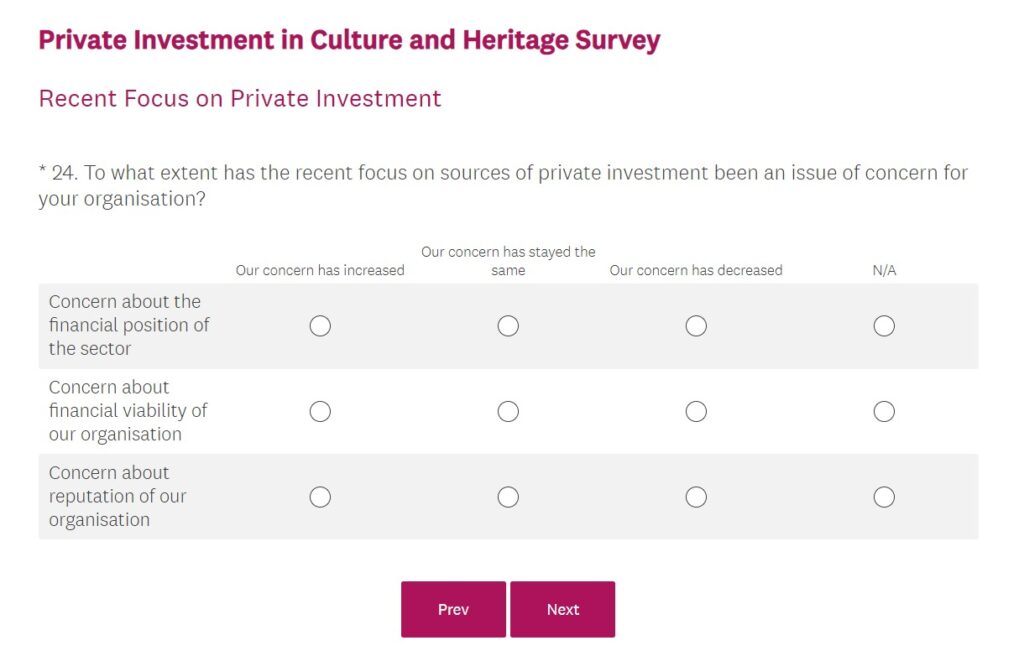

TOM: Oh man, that survey made me so angry! It was launched late August by Creative Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland and Museums Galleries Scotland and the framing of the whole thing was just urgh. Questions around the “the recent focus on sources of private investment” and how they have made life sooooo tough for poor old Scottish arts organisations. Nothing about their complicity in genocide by taking money from sponsors like Baillie Gifford, nothing about the cultural communities they claim to represent, nothing about their gross negligence in never bothering to actually ask where all this lovely money was coming from. Instead, you can see so clearly from the questions what the announcements will lead with: it’s so tough being a Scottish arts organisation because of all those horrible artists who keep asking us not to be complicit in genocide. Why can’t they just leave us alone so we can hang out with the asset managers and the Zionist “philanthropists”. It’s just throwing artists and cultural workers under the bus yet again rather than facing up to this sector willfully ignoring its own complicity.

CRYSTAL: Well, tell us how you really feel!

TOM: I mean, I do have some sympathy. Accessing public funding in this country has become a full-time job and it’s a joke. So many organisations spend all of their time trying to access funding that by the time they actually get some they don’t really have any capacity to actually programme things or think about what’s important. But many of the directors of Scotland’s major cultural institutions have been in place for years and years. They have presided over the journey to where we are now and yet somehow they see themselves as victims. It’s really quite astonishing.

CRYSTAL: Genuinely one of the things I have most struggled with since moving here, but especially so in the last year trying to talk to institutions about Gaza and Palestine, is the overwhelming sense of self-victimisation. If people who lead institutions only work together as a collective organising body in emergency situations, then I can see how they might see themselves as individual victims. But it is a deeply inappropriate perspective because it underestimates and therefore undermines their institutional power and leverage, particularly collectively. There’s also the fact that the sector’s inability to understand, or perhaps to admit, that ethics, especially in relation to funding, is more than just reputational damage or inconvenience, but legal as well as life and death in some cases. This is why much of the focus of organising by artists and arts workers is framed around complete overhaul rather than piecemeal reform.

TOM: Agreed. Cultural managers are always in an interesting position, negotiating between those with money and power (government, “philanthropists”, corporate sponsors etc) and the precarious artists and creative practitioners who they’re supposed to support. But time and again, when the dividing lines are drawn (and the dividing lines are always being drawn and redrawn) they side with power. Edinburgh Book Festival’s treatment of Fossil Free Books is such a textbook example of liberal self-positioning in that regard that it should be studied in schools. And now, in a new piece in the Bookseller, the imagined worries of the director of Hay festival are being given more weight than the actual, real deaths of tens of thousands of Palestinians. It’s just disgusting.

CRYSTAL: Hugely agree. Frankly, cultural institutions cannot exist without culture workers and the Fossil Free Books campaign made that abundantly clear. Related to what I said above about overhaul, I think Creative Scotland and cultural institutions across the country have a broader lobbying job at which they are falling short. These organisations lack joined-up thinking. Instead of single-issue campaigning that results in little more than crumbs for the arts sector, why isn’t the cultural sector in Scotland actively pursuing the introduction of a universal basic income? Where is the policy work from SCAN to support a campaign to meet the basic needs of everyone in order to enable cultural workers to live and create more sustainably? Seeing the ways in which the cultural sector here constantly uses, for example, the language of radical care when it continues to perpetuate systems of under-funded, competitive, exploitation of artists instead of genuine radical care for all makes me rage. Radical care means action. It doesn’t mean empty words.

Image credits (from top):

1. Protest outside Holyrood Palace, 5th September 2024

2. Mark Lester plays Oliver Twist in Oliver!, 1968. Photograph: Allstar/ROMULUS

3. Installation shot from Residence Residence exhibition at Generator Projects, Dundee, September 2024

4. Sample question from Private Investment in Heritage and Culture Survey, September 2024