As far as ancient sculpture goes, the bust of Lucius Verus—co-emperor and adopted brother of Marcus Aurelius—in Rome’s Palazzo Altemps museum is attractive enough, but it’s not the sort of artwork that dazzles you enough to stop for a closer look. There’s a cricket-ball-size chunk missing from the front of the emperor’s curly quiff, a bit of abrasion to his beard and some damage to the lips, but the torso’s stylised armour is in excellent condition, the emperor’s enormous nipples protruding from his breastplate. Although I can’t remember which academic wrote it, I remember reading something once about how the ancient Greeks liked to look as naked as possible, even when wearing armour. An aesthetic habit the Romans clearly adopted.

The reason that Verus’s torso is in such good nick and his head is a mess is because they’re actually two separate pieces: one Renaissance, one ancient. They’re also two different varieties of marble, despite looking almost identical. If I’d trusted my art-historical intuition, I’d have realised that the sculpture was a composite. But I know for certain because of a nifty diagram on the wall, a line drawing of the sculpture shaded white for the ancient head of microcrystalline marble and the torso shaded dark grey for the Renaissance bust of grey-veined white marble.

Since visiting Palazzo Altemps and, in particular since admiring its clever diagrams, I’ve thought a lot about the ways in which most museums fail to acknowledge how works of art have been transformed, deformed and reformed over time. Why don’t other museums display similar diagrams for paintings showing how they’ve been overpainted or how the varnish has been stripped back and reapplied? Why isn’t there greater institutional acknowledgement and communication of the fact that most of what its visitors encounter hanging on walls or standing on plinths has likely undergone significant transformation or restoration in the years since its first creation?

Such questions form the premise of Salvatore Settis, Anna Anguissola and Denise La Monica’s new exhibition, Recycling Beauty, at the Prada Foundation in Milan. The chief focus is on the reuse of Greek and Roman antiquity in post-antique contexts, but the show frequently strays from—or maybe expands upon—its central theme to consider misattributed works, later copies of lost antique works, reconstructions of antique statuary and the breaking up and dispersal of ancient artworks to new locations.

I desperately wanted to love this exhibition. I spent nine hours on a train, travelling up from Naples and back in one day just to see it. Settis is an intellectual hero of mine (I did a PhD in classical reception once upon a time and Settis has always loomed large in that field) and the exhibition, Portable Classic, which he co-curated with Davide Gasparotto at the Venice Prada Foundation in 2015 (alongside the equally-brilliant Serial Classic in Milan), ranks as an all-time favourite. Portable Classic looked with laser focus to the post-15th-century resurgence of interest in classical art and the history of collecting scale replicas of ancient classics. The whole thing was a masterclass in curating, and showed what great things can result from tons of money, a thoroughly scholarly curatorial team, stunning exhibition design (by OMA), and the cultural muscle to be able to pull in loans from the likes of the Prado, H.M. Royal Collection, the Louvre and the Uffizi.

By contrast, Recycling Beauty, is a bit of a mess. It lacks the same focus as its predecessor exhibitions and suffers from a sense of confusion and dilution. Certain pieces speak to the exhibitions themes better than others, but I frequently find myself standing in front of an artwork wondering what it’s doing here. A Roman-age marble disc depicting, initially confusingly, a deposition of the cross scene is a good example of something that worked well. It’s one of the few pieces in the exhibition which is fairly easy to interpret without the accompanying labels—this is a show where almost nothing makes sense without reading the explanatory text. What was once a Roman bas relief depicting three men carrying a wounded fighter, perhaps a gladiator, was in the 16th century transformed into a deposition motif with the simple addition of haloes around all the mens’ heads. I burst into laugher when I saw it and understood the transformation that had taken place. This piece on its own makes an amusing and intelligent argument about how ancient art was often reworked in later periods for completely different, often antithetically-so, purposes.

Indeed, many of the exhibition’s most successful inclusions speak to the intellectual (and visual) gymnastics performed by later religious appropriators of antique artworks to repurpose them for ecclesiastical use. A large mid-2nd century CE statue of Antonius Pius—which was already a reconfiguration of a portrait bust of the emperor and the body of a Roman priest—was later transformed into a depiction of Saint Joseph through the simple addition of a staff of flowering lilies, here indicated by an unlovely cardboard replacement for the golden rod that was removed, probably in the early 1900s. Even more amusingly, an enormous 1st-century BCE Roman kraterhad been appropriated, though not transformed, for use as a baptismal font in Gaeta Cathedral, despite the fact that its surface is covered with decorative depictions of Bacchus, god of wine and merry-making.

Despite encountering objects of interest and delight, more often than not I found myself frowning in front of works, confused about their inclusion. One of the gilded bronze peacocks that since the early 1600s decorated the Vatican’s famous Courtyard of the Pinecone (now in the Vatican Museums collection) is included in Recycling Beauty as an example of repurposed antique art—the peacocks are thought to have originally ornamented Hadrian’s Mausoleum. But what’s surprising or even that interesting about Hadrian’s peacocks being repurposed for the Vatican? Peacocks aren’t an obviously pagan symbol. There’s no frisson, interesting contradiction or spark of delight in this example. Why, I can’t help but wonder, was it chosen in the first place.

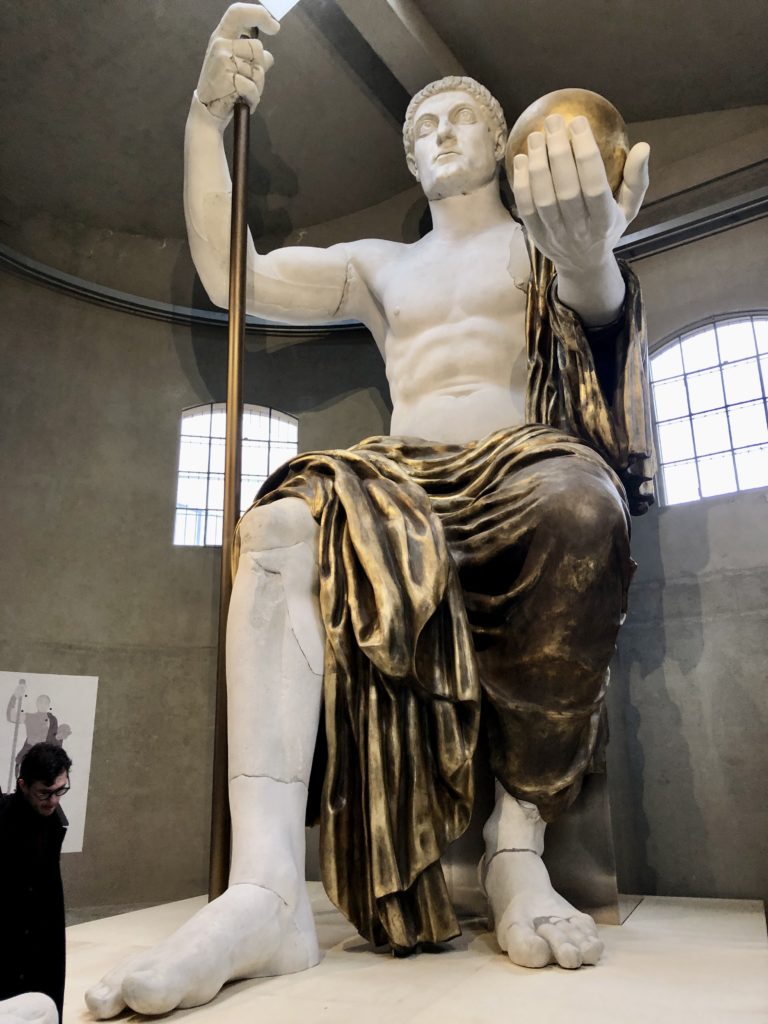

Many works speak to misattribution—a sculpture of two boxers, thought to be antique but misattributed and now known to date from the Renaissance, for example—or imaginative remaking—such as the so-called Magdalenaburg Youth, a 16th-century copy of a lost Roman bronze of a nude boy in a contrapposto stance, thought to be original until the late 1980s. In the exhibition’s second space, there sits an absolutely enormous reconstruction of the famous Colossus of Constantine, long known for, in particular, the pointing finger and feet fragments housed in Rome’s Capitoline Museum. Although the reconstruction carried out by Factum is an impressive work of art-historical scholarship, and provides the exhibition’s must-have photo op, like the works associated with misattribution or straight copying, the reconstruction feels separate to the supposedly central themes of reuse and recycling.

Recycling Beauty is a strange exhibition, an attempt to bring together a huge swathe of disparate themes under a catch-all phrase that tries, I think, to cover too much ground. The exhibition leaflet even includes a list of 79 places and buildings around Italy to visit should one wish to see further evidence of antique recycling in architectural practice. There’s a watery, nebulous quality to the show which wasn’t in evidence with the luminous clarity of the Portable/Serial Classic exhibitions that made them so exciting and so stimulating to visit. I left the exhibition feeling glad that I took the trouble to visit, but disappointed all the same. Recycling Beauty needed a tighter focus, more clearly expressed.

Recycling Beauty is at Fondazione Prada, Milan until 27th February 2023.

Image credits (from top)

1. Exhibition view of ‘Recycling Beauty’, photo Roberto Marossi courtesy Fondazione Prada

2. Exhibition view of ‘Recycling Beauty’, photo Roberto Marossi courtesy Fondazione Prada

3. Oscillum with deposition scene, Roman age, reworked in 16th century, marble, photo Crystal Bennes

4. Antoninus Pius as Saint Joseph, mid-2nd century CE, marble, photo Crystal Bennes

5. Reconstruction of the Colossus of Constantine, 2022, plaster casts, gesso powder, resin, bronze powder, Factum, photo Crystal Bennes

6. Krater with Bacchic reliefs, mid-1st century BCE, pantelis marble, photo Crystal Bennes