This series of four conversations was originally published on Roman Road Journal, 2018

Science has long been characterised as a quest for knowledge – after all, the very word, ‘science’, comes from the Latin verb, scio, meaning ‘I know’. Definitions of art, on the other hand, have arguably shifted more dramatically over the course of its history, from something that emphasises certain skills to the conceptual carte blanche we think of today as ‘contemporary art’.

But since the professionalisation of art in the second half of the 20th century, and especially since its academicisation over the past few decades (witness the proliferation of MFAs in the 1960s and practice-based PhDs from the 1990s onwards), artists and those around them have increasingly resorted to justifying art on the basis of ‘new knowledge’. Doctoral study at Glasgow School of Art, for example, is underpinned by “the generation of new knowledge and understanding through creative practice, scholarship and criticism.”

But what types of knowledge can a fine art practice generate? Should the arts be seeking to justify themselves in the language of science, and, in a world already swamped by big data, is more and more knowledge necessary, or even desirable?

CRYSTAL BENNES: In my recent interview for a practice-based PhD at the University of Northumbria, I was asked what new knowledge my work would produce. It’s a fairly standard question but it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot. With my background in academia (I have an MSc, MA and PhD in Classics) I’m pretty accustomed to the idea that academic research ought to result in new knowledge. But it’s much less clear how fine art practice and the measurable production of new knowledge ought to relate to one another. You have to do some serious mental gymnastics for those two things to bend and fit together.

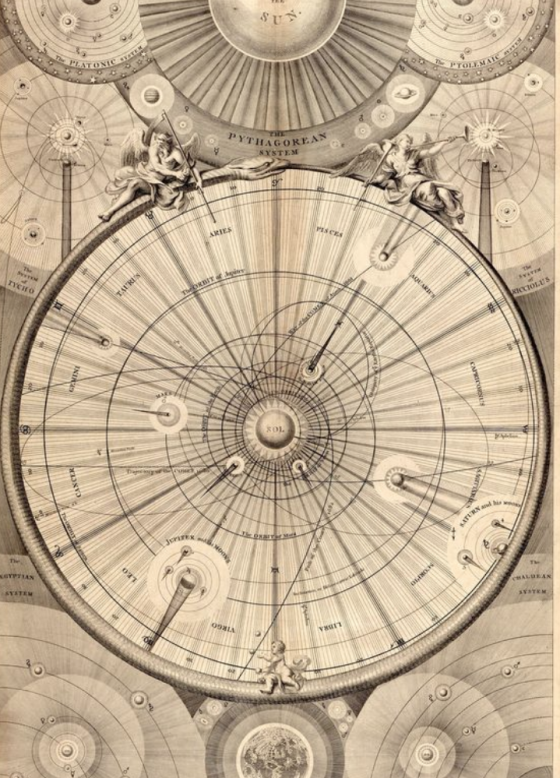

A few years ago, I read Stuart Firestein’s book, Ignorance: How it Drives Science, and there’s a bit from the intro that has really stuck with me. He says that in 1687, Isaac Newton probably knew all the extant science that there was to know at the time. Today, amazingly, the modern high school student probably knows more scientific information than Newton did, but a modern professional scientist knows a much smaller percentage of the available scientific knowledge. “As our collective knowledge grows, our ignorance does not seem to shrink,” he writes rather pithily.

TOM JEFFREYS: And this problem – if it is a problem – is only accelerating.

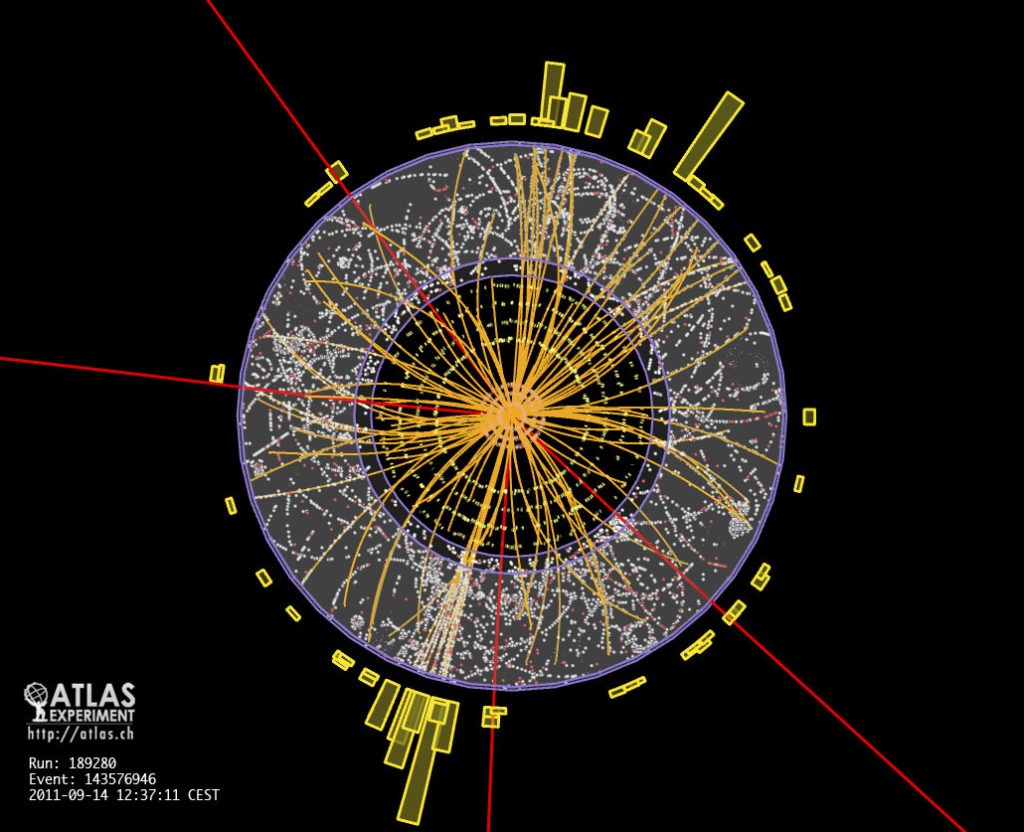

CB: Exactly. Today, CERN, to take just one famous example, produces so much data – around 75 petabytes per year – that they can’t provide enough computing power on site to store and process it. They now have something called the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid which means data is stored and processed all over the world.

TJ: By coincidence, I’m reading J.R. Carpenter’s book, The Gathering Cloud, at the moment and her writing is super-attuned to the massive ecological damage that these vast computers require. And it’s not just big science: Carpenter mentions that the New York stock exchange produces up to two thousand gigabytes of data per day. Taken together, server farms would be the fifth largest country on earth in terms of energy consumption.

Modern technology often advertises itself as ethereal, non-material and frictionless, but Carpenter, and media archaeologists like Jussi Parikka, draw our attention to the massive energy costs, the extraction of rare minerals, the vast environmental damage, the appalling health effects on the people working to polish the metal of your iPad etc. The data clouds of the 21st century are powered by the dirty coal energy of the 19th, as Carpenter points out. “Data is physical,” she writes.

CB: Absolutely, the ecological impact makes this question of production a hugely important one. But what interests me in terms of the relationship between art and science, is that not only is there not enough room to store the data, there also aren’t enough people around to analyse all the data. So, at CERN, for example, a huge amount of time is spent writing and rewriting algorithms which siphon off only the most “interesting” data from the detectors. Of the 600 million events per second detected by detectors, two stages of algorithms filter out only around 100 or 200 events of interest per second – which is still a ridiculous amount of data to get through.

TJ: So, if people aren’t even really looking at all of the data that is being produced, why do we need to keep producing more of it?

CB: Well, I think there are a number of reasons. Partly, this is territorial – to do with funding – but I think there’s also a susceptibility to believe that, if we just obtain more and more data through bigger and faster experiments, we’ll crack the code. We’ll finally figure nature out! It’s symptomatic of a broader cultural insanity.

TJ: I’m pretty certain this is one of the things that Rupert Sheldrake has been banging on about for a while.

CB: There are loads of great philosophers of science, including people like Sheldrake and Mary Midgely, who talk a lot about these questions.

TJ: It also seems to me that science fits pretty well within a metrics-based approach to knowledge. Most of that obsession with metrics is a result of economics (thanks, capitalism!) and economics is always at pains to seem like a science. It reminds me of that Rebecca Solnit line that “science is how capitalism knows the world”. The obsession with new knowledge is surely a product of capitalism’s need for novelty?

CB: And now art, and the humanities more broadly, find themselves trying to fit into the same box, which I think is problematic in so many respects.

TJ: Trying, and often failing. I always see the argument made that science produces knowledge and art is only able to interpret that knowledge or help to disseminate it. To my mind, this sets up a hierarchy in which only scientists have access to objective truth and art is just playing around with subjective responses. The problem is that art then feels the need to justify itself by making claims to be a co-producer of knowledge, but in doing so only resorts to justifying itself within a logic defined by a scientific approach.

CB: Exactly.

TJ: So, if we’re going to be critical, or at least not entirely in favour of, this metric-based approach to knowledge as data, in which more equals better, then does art (and the humanities more broadly) offer different kinds of knowledge that might be more useful or more interesting or less ecologically damaging? Embodied knowledge, practice-based knowledge, experiential knowledge etc. All of these things are valid and important and different from the kind of data-based knowledge that a lot of modern science produces.

CB: Although this is admittedly generalising, scientific knowledge needs to be tidy, reproducible, quantifiable, methodical, etc. By contrast, the production of knowledge in art can be messy and weird and even a bit nonsensical. When we talk in English of knowledge, I always think of the obvious fact that our language only has one word for knowledge. Many languages have multiple words for knowing. In French, for example, you have both savoir and connaître, which signify different kinds of knowing. Knowing something as a fact versus knowing how to do something as a practice or technique, for example.

TJ: One thing we haven’t really discussed is whose knowledge we’re talking about, and I don’t just mean who gets access to this knowledge socially, politically, economically etc. The phrase ‘new knowledge’ implies that there is a huge bank of knowledge somewhere and we’re all just chucking stuff into it. But is that how knowledge works? I mean, knowledge and data are not the same. Data may be stored in some vast server farm, but, to me, knowledge cannot exist independently of a living, conscious mind.

Science justifies itself through appeals to an abstract idea of knowledge as something that exists outside of life, but that’s a myth, surely. If we take the library as an analogy, then today’s big data scientists are sitting at their typewriters, churning out billions of books and chucking them into the library without reading them. The artist is then like a librarian, suggesting combinations of existing books for people to take out and read. The librarian is not producing new knowledge in the sense of writing books but they are encouraging individual people to expand their own knowledge and to think differently. I would say that knowledge is more important than data and thinking is more important than both of them.

CB: In this context, I think perhaps ethics is one of the key types of knowledge that art is involved in.

TJ: Isn’t ethics more a mode of questioning rather than a type of knowledge?

CB: Exactly, and as with your librarian analogy, I don’t think art does necessarily create new knowledge, nor does it need to. But ethics is absolutely crucial for justifying knowledge or allowing us to make decisions based on that knowledge. At Northumbria, there’s a research group called The Cultural Negotiation of Science and I think this is a great way of looking at what a lot of artists engaging with science are doing – it’s not necessarily about creating new knowledge per se but about interpreting, criticising and analysing the scientific knowledge which has been produced or is being produced. The point there, I think, is that endless production of knowledge without criticism and interpretation of that knowledge is worthless.

FURTHER READING

J.R. Carpenter, The Gathering Cloud, 2017

Stuart Firestein, Ignorance: How it Drives Science, 2012

Gisela Williams, Are Artists the New Interpreters of Scientific Innovation?, 2018