To Venice! The waters are rising, the palazzos are sinking, the art is expensive, and the mood is, err, buoyant. Kind of. For one week only the city is once more overrun with boozy artists, leering collectors, crisp-suited dealers, frazzled PRs, exhausted critics shut up in hotel rooms frantically hammering away at laptops, and, of course, us. Yes, it’s time to dig out the linen suit again. The Venice Biennale is back.

After 2015’s political onslaught courtesy of curator Okwui Enwezor, this time promised a shift in emphasis, with the crown passed to Christine Macel of the Pompidou – just the fourth women curator in the Biennale’s history dating back to 1895. The title of her main exhibition? Viva Arte Viva! – meaning “Long Live Living Art” or something…

TOM: OK, Venice, where shall we start? In the Arsenale?

CRYSTAL: That seems sensible.

TOM: Christine Macel’s main exhibition, Viva Arte Viva, opens with an intriguing statement – that it has been “designed with artists, by artists and for artists”. The suggestion seems to be that artists are often bottom of the art world food chain and Macel aims to put them back at the top, or somewhere near it. I wish someone would do the same for writers…

CRYSTAL: Good luck with that one. As we’ve said a million times, it’s the bloody fault of art critics and writers for effectively turning into mouths-for-hire. Now no one takes us seriously and we’ve somehow ended up at the bottom. Even lower than the artists!

TOM: No wonder you’re calling yourself an artist these days… So after last year’s sledgehammer politics, things were much calmer, less didactic this time around. Enwezor’s show was pretty macho at times – lots of guns and loud noises – whereas Macel’s focuses more on textiles, weaving, domestic labour. If it felt more “feminine” perhaps, it’s interesting that actually only 35% of artists in the exhibition were women – that’s down a smidge from last time. It’s interesting also to compare it to 2011’s Encyclopaedic Palace – if that was about exploring the limits of what art could be, then I think Macel is asking us to reflect more on what art can actually *do*. What is the role of the artist in different societies? So most of the work here had a pronounced social agenda. Lots of community projects. Lots of art as catalyst for social or political change.

CRYSTAL: I know that didactic is a bad word in the post-post-modern art world, or wherever we are, but I really don’t have any problems with well-informed didacticism. But I think ‘much calmer’ in this case is a rather charitable way of saying boring. Flat-line. Like wandering aimlessly through the social spaces of a gated retirement village. And even though It was fairly easy to see what Macel was trying to do in terms of making claims for traditional practices and crafts and the value of domestic labour, it was much harder to understand what it was she actually wanted to say. It came across in many places as drifting, hippie nonsense.

TOM: Ha! Yeah, I remember you describing Anna Halpin’s work as “American woo woo”!

CRYSTAL: What can I say, I know my countryfolk. I mean, a bunch of people stomping around in a ‘planetary dance’ to help free a hilltop from a rampaging serial killer. Riiiiiight.

TOM: There was a lot of that kind of stuff, right? On one Ernesto Neto piece it read: “art is the connection / spiritual voice/ spread the art / that comes from you”. I mean, really.

CRYSTAL: Oh my god, that Ernesto Neto work! He puts a huge tent, a replica of a Huni Kuin Indian ceremonial meeting place, and then BRINGS some of the Indians to Venice so we can all see how deeply engaged he was with that community. I saw a video clip on social media where he was all, with these intensely meaningful eyes, like, “four years ago, I went to the forest, and I began to understand the hidden dimension and the huge knowledge that the indigenous people have.” So then I thought, bingo! I’m gonna just pack all that shit up and bring it to Venice, yee haw!

TOM: There was a fair amount of that kind of patronising gap year attitude wasn’t there?

CRYSTAL: Arrrghghghghlph!

TOM: Good point. But actually the one work that really pissed me off was by Japanese artist Shimabuku. At first glance it looked like some red-hot media archaeology stuff and I was all ready to quote Jussi Parikka or JR Carpenter and sound knowledgeable. But actually, by placing iPhones side by side with prehistoric axe heads, Shimabuku wasn’t emphasising the differences between these two things but effacing them. The piece was called “Oldest and Newest Tools of Human Beings”. But tools and technology are not the same. Technology is so much more than a tool, an iPhone is so completely different to an axe in terms of ecological impact, social change, economics, politics… and to fail to realise that is effectively to turn your work into a glorified ad for Apple. The piece where he’d turned an iMac case into an axe: I mean, if only he’d bothered to find out the ecological damage that creating those shiny covers creates in the first place – not to mention the hideous health risks for those forced to make them. Man, that made me cranky.

CRYSTAL: That did look a bit like an ad for Apple, come to think of it. But it didn’t annoy me as much as it did you. It didn’t provoke any emotional response whatsoever, actually. Which is a bit sad.

TOM: There was some good stuff though. I liked Marie Voignier’s video Les Immobiles – looking at colonial impacts upon local cultures and ecology, via the reminiscences of a former big game hunter. There was a nice moment describing two exploitative colonists, the Trechaud brothers I think, who paid their African staff in a currency that could only be used in the shop that they ran, so they got it straight back again and the African staff would always be chained to their employers. I mean, this is exactly how a lot of foreign development aid loans work today: “Here’s a bunch of cash, developing nation. But you have to spend it on our goods and services.” “Gee, thanks.” “Oh, and here’s the bill for the interest. Toodles!”

CRYSTAL: You’re preaching to the choir here! Hasn’t any artist made a film about the outrageous practices of the IMF? Or the damage done by the armies of white, American college kids with saviour-complexes who join the Peace Corps to, you know, fix Africa. If artists or curators are going to try to “understand the hidden dimensions” of anything, I often wish they’d interrogate their own intentions before turning their attention to the saving other people. Man, nothing incites a rant quite like Venice!

Anyway…

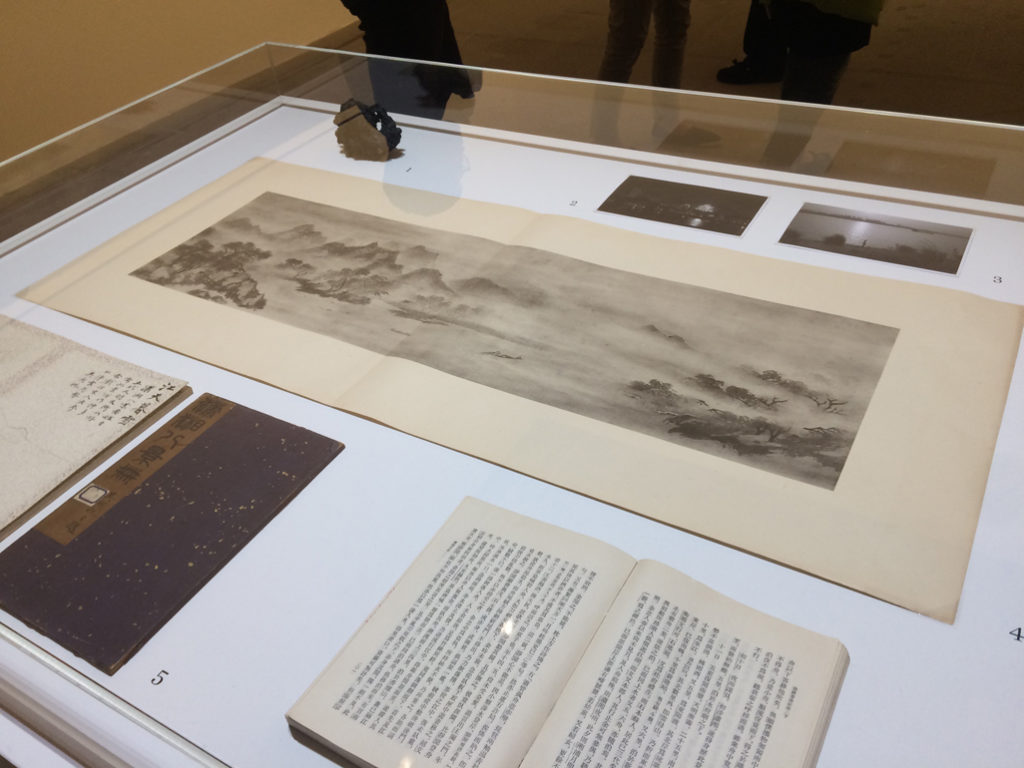

On a completely different note, I quite liked Hao Liang’s ink paintings on silk. If you’re going to be boring, you might as well be boring intentionally and beautifully. I’m also a sucker for reinterpretations of traditional Chinese painting, so I couldn’t help but be intrigued by his Eight Views of Xiaoxiang. But I have to say, I think I preferred the vitrine of research materials to the actual paintings, especially the little reproduction of the 13th-century Chan monk Mu Qi’s amazing “Fishing Village at Sunset” from a more traditional Eight Views series. Actually, I wish there had been an entire room dedicated to Mu Qi’s original series – I would have sat and looked at that for ages.

TOM: I also liked Les Mingwei’s performance installation, The Mending Project where the artist sat there weaving little motifs into mass-produced clothing. Threads connected the making to the product and then connected into a kind of map across the wall. There was definitely a quiet, contemplative vibe going through the whole thing: Anri Sala’s wallpaper installation; Sopheap Pich’s ruddy red pattern paintings; Michelle Stuart’s Baltic Boat Book. Normally, this is exactly the kind of work I tend to like, but in the context of the Biennale – when you feel the ever-present pressure to just keep moving – it can struggle to get you to stop and listen properly.

CRYSTAL: I didn’t like the Mingwei piece. I might have liked it in a different context, but here it just felt like another artist-animal performing in the Macel zoo. It somehow felt like an exhibition grounded in that “what’s your source for that?” thing infecting social media at the moment. As if the physical presence of the artist, or the migrant, or the refugee is proof of value. But that’s such a one-dimensional way of thinking about the value of different kinds of labour, different kinds of actions. But yes, I know what you mean about the difficulties in looking. It also felt like there were so many more people, especially tour groups, at the opening than ever before, so you really had to fight to look at most of the work. Which is not ideal.

TOM: Yeah, it makes small, subtle pieces virtually impossible to spend any time with.

CRYSTAL: This is the first Biennale where I have hardly any notes and images from the Arsenale of things that either interested me or irritated the hell out of me. There was hardly anything I found really repellent and only two things I really enjoyed. Much to my surprise they were both video pieces!

TOM: The times, they are a-changing.

CRYSTAL: There was Marcos Ávila Forero’s Atrato, a piece from 2014 about the forgotten practice of river percussion in the Colombian Amazon. It was somehow completely foreign and totally familiar at the same time, without the dazzling-but-empty high-production values that many art films have adopted lately (cough, Pierre Huyghe at Louis Vuitton). I really enjoyed the video in and of itself, but appreciated even more the feeling of a thinking, enquiring, curious artist behind this project.

TOM: Yeah, I saw that at MRAC in Sérignan recently – it worked really well there too.

CRYSTAL: There was also Guan Xiao’s super-short three-channel video installation from 2013, David, which was strange and really very funny. It was kind of loving piss-take on the weird ways we bestow celebrity status on various artworks without either really looking at them or asking why elevate these works to semi-divine cultural standing and not others. I liked it. It made me laugh, and at the Biennale, a work that makes you laugh is gold.

TOM: Weirdly, there was quite a lot of video that we both liked across the Biennale. For Slovenia, Nika Autor’s agitprop newsreel about train travel and refugees was great. I wish I’d stayed to watch more because the book of essays and poetry they published alongside is wonderful. And there was that brilliant one at the Future Generation Art Prize, Vajiko Chachkhiani’s Winter Which Was Not There.

CRYSTAL: Oh, that was marvellous. God, I loved that.

TOM: It was in the same room as that Aurelien Froment jellyfish one from last time so I was already willing to like it, and it didn’t disappoint. You watch as a memorial statue to some unidentified dictator is winched up and out of the sea and plonked on the ground, face-down, totally without ceremony. A lugubriously moustachioed man then attaches it to the back of his truck and we watch as he drives along, with his big old dog in the passenger seat, through the beautiful landscapes of Georgia and into the city. As they drive, the statue is dragged along the ground and gradually falls to bits. Weird, amusing, full of personality and genuinely thought-provoking. It made me think about the overlap between public and private memory as well as how to handle political legacy when a culture suddenly changes. Is iconoclasm the answer? Should we conserve everything? It also made me wonder about how these kinds of memories differ between the city and the countryside – I bloody loved it basically.

CRYSTAL: I’ve read a couple of things mentioning Chachkhiani’s video and something I love is that people can’t agree on who the statue represents, whether it’s a political leader or a copy of the man driving the truck. What I really enjoyed about it was that, iconographically, it’s very familiar. But the narrative structure is so ambiguous that it somehow feels very original. Earlier today, I was reading an interview with Jonathan Lethem, who wrote that brilliant essay, ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’. In the interview he talks about how the relationship between familiarity and novelty is underrated, and that people always want to praise the aspects of something which seem really radical to them. Nobody ever says, “Oh, I loved this book! About 75% of it was extremely familiar to me!” As soon as I read that, I thought of Chachkhiani’s film. It was the 75% that was somehow so familiar which I think made it so brilliant.

TOM: You and your obsession with copying…

CRYSTAL: And, I can’t believe I’m saying this, but there was another video piece in the Iraq pavilion which I really liked. Luay Fadhil’s The Scribe. It was short, barely four minutes, and exhibited in quite an illustrative way inside a vitrine about street scribes in Iraqi history. But it was enchanting and poetic – a set piece in which a man dictates a strange, meandering and rather romantic divorce request to a street scribe. It completely transported me to another world and left me wanting more. I think there’s still a tendency by too many film-based artists to treat video as a punishment or endurance test, rather than appreciate that the medium can be incredibly effective in short, concentrated doses.

TOM: I thought Iraq was good again this year. I mean, no single work really sang to me like Rabab Ghazoul’s Chilcot inquiry video from last time. The Francis Alys paintings were lovely and the overall exhibition worked really nicely. And the venue was drop-dead gorgeous.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, the exhibition was ok. I didn’t love it like I did the last one, but the building – Palazzo Cavalli Franchetti – was stunning. Being able to snoop around inside all of Venice’s ornate palazzos and churches is always one of my favourite things about the Biennale.

TOM: Shame they always have to fill them with art! Finland was another one with a great video.

CRYSTAL: Although, I mean, they paid you to say that…

TOM: Ha! True. I was hosting an event at the pavilion, but I did actually genuinely like it! I interviewed the artists last year as well and their approach – as well as being silly and childish – is super-interesting at the same time. I remember, when we first came to Venice, we found it weird that everyone just totally ignored the question of national identity and nationalism that is inherent in the structure here. So it was great to see Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen tackle that head on, exploring both the lasting power and the inherent absurdity of these kinds of myths. Can there still be a Finnish national stereotype when the whole world is Finnish? Plus the work was genuinely hilarious. Even you were laughing at all the stereotypes of Finland.

CRYSTAL: Yeah, parts of it were genuinely hilarious, although I wonder if that’s only because we lived in Finland for two years and found the pot-shots at national stereotypes amusing. But then it all took a tedious turn down the road to puerile cock-and-balls jokes. Shitting and fucking. Boooooring.

TOM: What about the other pavilions in the Giardini? I kind of liked the Belgian one. Black, bland, beautiful photographs with cryptic titles like Z.Z.-T.T.-17#2. I mean, it was so Belgian!

CRYSTAL: That was Dirk Braeckman. It’s funny because I tweeted something about the Belgian pavilion being aesthetically perfect bland nothingness, and a bunch of people were like: that sounds amazing! I guess it’s an interesting point in the context of the Biennale, which has been on showy-showy-politically-worthy-ethical-ego-trip mode in the last few years. A bit of aesthetic perfection can seem a godsend sometimes, but I think the overall blandness of this year meant that it wasn’t really needed. For me, anyways.

TOM: I loved Greece too. Another video piece – this time with a glossy black installation leading you to the film itself, which showed a group of scientists and bureaucrats arguing over the ethical implications of an experiment on different types of blood cells. The metaphor for multiculturalism was a little laboured, but I loved the way it questioned the extent to which fairly niche scientific discoveries can often function (very badly) as models for larger ways of thinking. We think of cities as organisms, say, or the brain as a computer. Or think back to the way Darwin drew on Malthus and was then in turn appropriated by the eugenics crew.

CRYSTAL: A little laboured? Jesus, the metaphor was a sledgehammer. HELLO IDIOTS! BEWARE METAPHOR!! I thought it was idiotic.

TOM: Haha and I loved the way the PR afterwards was like: “Did you get that it was a metaphor?” I mean, how could you not get it! Anyway, what did you make of the other pavilions this year? Last time it was just a litany of WTFs I seem to recall…

CRYSTAL: Although not a litany, there were plenty of WTFs for me. The fact that the Swiss Pavilion not only forcibly appropriated Giacometti (who repeatedly refused to represent Switzerland in Venice), but called its exhibition Women of Venice (after a 1956 presentation of Giacometti’s work in the French pavilion) and then showed films about the life of an unknown female artist, which seemed to revolve wholly around the idea that the female artist’s value derived from her association with Giacometti, infuriated me. This happens so often and it drives me crazy. I also thought that Brigitte Kowanz and Erwin Wurm’s ‘interactive’ installation in the Austrian pavilion was stupid, but people seemed to enjoy sticking their bums into holed-out caravans so…

TOM: People will always enjoy sticking their bum in things. That’s the first rule of interactive art. Ok so where next? The Giardini main exhibition?

CRYSTAL: Sure. No wait. I forgot something I really liked! The Korean pavilion! There was a work by Lee Wan, Mr. K and the Collection of Korean History, which I thought was just so interesting. It builds on the fairly common found-archive trope – the artist apparently purchased a box of 1,500 photos of Mr. K, a journalist and businessman, with images dating back to the 1930s and spanning a vast swathe of modern Korean history. But these found images are woven into a chronological tapestry of other texts and books, newspapers, objects and images to tell the story of Korean politics. You have this wonderful intersection where there’s a personal story to hang the history on, but you don’t entirely trust the ‘found archive’ story because of the constructedness of the display. It makes you really look at and interrogate the materials in front of you. I found it incredibly fascinating and very well done. In fact, I wished that they would have had only this one work in the exhibition and gotten rid of everything else.

TOM: Agreed. Now shall we talk about the Giardini exhibition?

CRYSTAL: Looking through my pictures, I can see that I didn’t take a single picture or note of anything there. That’s depressing. But sure, talk away…

TOM: The main heart of the show is an entire gallery given over to Olafur Eliasson, who in turn has given the space over to migrants living on the Venice mainland. They’re all sitting at desks making geometric shapes out of straws and what-not for profits that get pumped back into the project. In the corner is a semi-circle of banked seats. It’s meant to play host to workshops and events, but mostly people are just sitting there charging their iPhones. It looks like a cross between children’s craft class and one of those stupid hubs for tech start-ups.

CRYSTAL: I found that whole thing just infuriating. It’s depressing how off the mark artists and designers so often are when they try to be worthy. Let’s face it. The point of these kinds of exercises is not to help migrants, nor refugees, but to boost the careers of the Olafur Eliassons of the art world.

TOM: Yeah, I felt that about the Tracey Moffatt exhibition in the Australian pavilion. Everyone seemed to rave about it but the images were meh and, god, those tote bags!

CRYSTAL: There was certainly something rather incongruous about seeing loads of people drinking prosecco at expensive art parties while carrying around bags that read “Refugee Rights” on one side and “Indigenous Rights” on the other, the “tote bag to be seen with” according to the Art Newspaper… I mean, I realise it’s shooting fish in a barrel to complain about token activism at the Venice Biennale, but people don’t give a shit about what it says on the tote bags. They just want the damn bags.

TOM: Ha! Where were we when that lady barked at a poor press assistant to give her free stuff?

CRYSTAL: I think it was Russia. I’m not even sure what she asked for, “swag” or something. The assistant was like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about,” and the lady was all: “You know, tote bags, catalogues. Whatever you’ve got, I want it.” It’s not as bad as it used to be, but there’s still a strong sense that people only come to get free stuff, go to parties, and network like crazy. Which I think is why it feels so ludicrously uncomfortable to see banner-waving refugee rights installations and slogans and whatnot. Even if their hearts are in the right places, it’s difficult for all that not to come across as misguided profiteering in Venice.

TOM: Agreed. But then what else do you do? If you’re a “social practice” artist and you’re invited to take part in the Biennale, you can’t just suddenly knock up a nice oil painting instead. I guess you could just refuse to be involved. I wonder how many artists actually do that…

CRYSTAL: Not many!

TOM: Another thing I often feel uneasy about is the way lots of those involved in the art world align themselves with refugees. Travelling because you want to is not the same as fleeing because you have to. What was that Theresa May line? A citizen of the world is a citizen of nowhere? What a ridiculous thing to say. A globe-trotting curator like Hans Ulrich Obrist is a citizen of the world. A stateless refugee is a citizen of nowhere. In no way can, or should, the two be compared – by ghastly Tory prime ministers or by artists themselves. Incidentally, I think one of the best comments on art and globalism were the words, ‘Scrivo in Italiano’, scrawled all over the English-language Biennale posters at one of the vaporetto stops.

CRYSTAL: Having said all that, I do think there was one work which exemplified a much more productive way of engaging with marginalised communities – in this case blind and partially-sighted people in Venice – and that was Antoni Abad’s BlindWiki project for the Catalonia in Venice presentation. This was the one thing which I had read about prior to coming to Venice that really excited me. It’s about mapping and cartographies, which I love, but it also engages with the specific history of Venice in such a compelling way.

TOM: It was lovely wasn’t it? Probably my highlight of the Biennale.

CRYSTAL: That boat tour we went on was the best 20 minutes of Venice, for sure. I loved our guide, Giulia, whose personal and historical narration of Venice was so different to anything I’d previously experienced in that city before. For one thing, so many experiences in Venice are mediated through the lens of tourism, but also of course, through the visual – especially in the Biennale! It was really something, on a bright, sunny day, to put on a black mask and be guided through the waterways of Venice without looking at anything, just listening. It felt like a genuinely meaningful connection to an under-represented community and a completely new way of understanding the city. Really very lovely.

TOM: It felt simple and honest. It didn’t make grandiose claims for itself and Giulia’s involvement was crucial. She wasn’t just representing a community or being present as a *type* of person. She was her own person. And our experience was down to her. Plus, by getting us away from the main Biennale it finally allowed for that moment of calmness and contemplation. Perfect.

CRYSTAL: Well, that’s a nice way to finish. Let’s go get some ice cream.

TOM: Done.